Let’s start with the “essnacks.” American gourmets may assert their epicurean credentials by casually referring to the tidbits that start a meal as amuses, but in Spain, which tends to look to the Anglo world for approbation and not the French, they are snacks. Or, Castilian pronunciation being what it is, essnacks. This is not, as we shall see, an insignificant point.

At dinners on consecutive nights at two of Spain’s top restaurants, the essnacks in question contained fruit. At the first, the fruits were speared onto toothpicks: a cherry with almonds, a strawberry pinned to an anchovy. The fruit was pallid, the pairing unexceptional. At the second, one essnack consisted of tiny orange segments, smaller even than those of the smallest clementine, that had been freeze-dried or treated with liquid nitrogen until their texture resembled candy more than fruit. The flavor was intense.

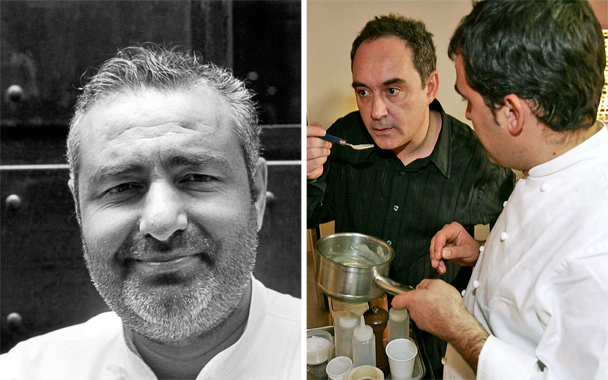

The cherries and strawberries were served by Santi Santamaría at Can Fabes; the tiny orange by Ferran Adrià at El Bulli. Earlier this year, both chefs had become embroiled in an explosive feud after Santamaría publicly criticized Adrià’s nontraditional culinary style. One could be forgiven, then, for taking the essnacks as metaphor.

The dirty secret of Spanish cuisine is that, until very recently, it wasn’t very good. The products—jamón, shellfish, tomatoes—were delicious, but except for the Basques, almost no one knew what to do with them. What I remember from my first trips to Spain in the 1980s is greasy fried eggs, greasy fried pork cutlets, rubbery fried squid, and no green vegetables at all, unless you count the canned peas in the (overcooked) paella.

Things were changing, though. In 1981, when Santamaría opened Can Fabes in the Catalan farmhouse where he, his father, and his grandfather were born, it was little more than a tavern, and he was content stewing white sausage with beans for 395-peseta meals. But as he gradually learned about Juan Mari Arzak’s new Basque cooking and France’s Nouvelle Cuisine, Santamaría’s own plates became more sophisticated. With the acclaim he received for marrying the flavors of his beloved Catalan countryside with French technique, Santamaría must have thought he was the revolution that Spanish cooking needed.

But of course, he was not; the revolution was his compatriot up the coast. Adrià is often seen as a genius born free from any context, national or otherwise. Yet there is something thoroughly Spanish about him, and it is history. What, after all, is the unique intensity of his creativity if not a powerful response to the atrocities and frustrations of the Franco dictatorship? Adrià’s work represents one face of repression’s effects: radical invention as a rejection of conformity, unbridled exuberance in the face of all that numbness and fear.

In this sense, Adrià is like that other genius to come out of Spain’s transition to democracy, Pedro Almodóvar. Their media are of course different—spherified olives and parmesan-infused air for one; sex, drugs, and neurotic women in stilettos for the other. But the reckless joy of their exquisite creations, the provocative art disguised as humor and sensuality, are the same. So too is the drive, relentless but unstrained, to create anew. If in today’s Spain you can hardly recognize the grim, authoritarian place that subsisted largely on fried eggs and sexual repression 30 years ago, you can thank, in part, Adrià and Almodóvar. Like the peaceful transition to democracy itself, they embody Spain’s unexpected liberalization.

The two men share another trait: Each has garnered international fame—or more precisely, fame in America—that has propelled Spain’s self-image. Like Penélope Cruz’s elated cry of “Pedro!” as she announced the 2000 Oscar for best foreign language film, the appearance of Ferran Adrià’s face on the cover of The New York Times Magazine is indelibly etched in Spanish cultural memory. These were the precise moments when Spaniards began to believe that they were just as good in film and food as any other nation in the world.

The backlash, when it came, was deeply shocking—even traumatic—to many members of Spain’s normally convivial fraternity of chefs. It wasn’t the first time that Santamaría had played the Rabelaisian populist, speaking earthy truth to gastronomic power (the previous year, he told a chefs’ conference that “all good meals require a good defecation”). But this time, his words struck a nerve. Receiving a prize in May for his new book, The Kitchen Laid Bare, Santamaría took the opportunity to criticize fellow chefs for “legitimating forms of cooking that distance them from the traditional,” and railed against “cooking with chemicals like methylcellulose whose consumption could be dangerous.” In case anyone missed the reference, he got specific. “I have an enormous conceptual and ethical divorce with Ferran; he and his team are going in a direction contrary to my principles.”

Within days, Euro-Toques, the European chefs’ organization, issued a statement expressing its indignation at Santamaría’s “act of aggression.” Fermí Puig, chef of Barcelona’s Drolma restaurant, wrote in La Vanguardia that the debate had pushed the public’s respect for chefs back a decade. Sergi Arola accused Santamaría of mounting a personal vendetta “out of envy.” Adrià regretted the damage Santamaría’s comments would do to Spanish cuisine’s reputation abroad.

The press chortled delightedly over the “War of the Stovetops,” but the story got mileage at least in part because it tapped into collective anxiety about how Spanish cuisine was changing. Santamaría might have concerns about the possible health risks posed by chemical additives, but his real worry was that the food he loved was being displaced by globalization, fast food, and molecular gastronomy. He lamented the passing of dishes like zarzuela (fish stew) from the repertoire of home and professional cooks, finding in their diminution not just changing tastes, but a pernicious loss of identity. The New Spanish cuisine might be new, he seemed to be saying, but it was hardly Spanish.

Spain is not the first country to experience changing culinary trends as a national identity crisis, but by pitting the traditional against the modern, and declaring that only the former was truly “Spanish,” Santamaría raised a familiar specter in his country. In the early part of the 20th century, poet Antonio Machado described the “two Spains”—one Church-bound, rural, centralist, conservative; the other free-thinking, urban, regionalist, liberal—as separate halves, each convinced that only it represented the “true” Spain, each permanently bound in a struggle to obliterate the other. Since then, the idea of the two Spains has been used to explain everything from the 1936 civil war to the surprise election results following the 2004 Madrid train bombings. And now it was rearing its head in the kitchen.

This mindset helps explain the ferocity of the debate that Santamaría unleashed. Spain may have transformed itself tremendously in the past three decades, but it has not wholly broken free of the tyranny of “either/or.” The idea that Spanish cuisine could encompass both zarzuela and reverse-spherified gnocchi is not yet truly accepted.

And yet. Two dishes from my back-to-back dinners last summer stand out in memory. At Can Fabes, it was the first course: barely poached Roma tomatoes stuffed with a creamy burrata, drizzled with basil oil, and set between sweetly briny razor clams. There was nothing new or particularly creative about the dish, but it was utterly delicious. At El Bulli, it was the last savory course: a gorgeous mosaic of sea anemones and rabbit brains. It was not, perhaps, a dish I would want to eat every night, but it was perfectly executed and thoroughly provocative. Neither dish, I should say, felt more “Spanish” than the other.

Many—perhaps most—Spaniards will tell you that they much prefer a good fabada to a spoonful of freeze-dried carbonara cream. But they will also tell you, as one cab driver in Barcelona explained to me, how they save up every year for a single meal at El Celler de Can Roca. And thus, for all the trauma provoked by Santamaría’s declarations, I choose to see in the debate a certain coming of age. On the heels of their spectacular culinary rise, Spaniards are now asking themselves what Spanish food is. And in asking that, they are, of course, asking what it means to be Spanish.

Although no one could have predicted it 30 years ago, it turns out that being Spanish can mean embracing gay marriage, and having a pregnant Defense minister, and reveling in an ethnically diverse culture. Does it seem far-fetched, then, to suggest that it can mean ending a meal as one does at Can Fabes, with a plate of lush regional cheeses, and it can also mean finishing as one does at El Bulli? There, the most spectacular dessert is called “Autumn,” and with its twigs, “sand” of pressed powders, and freeze-dried chocolate “leaves,” looks exactly like a forest floor in November. A waiter sets down an ancient-looking chest and you open one hidden drawer after another, finding in each one a different sweet surprise.

Pinterest

Pinterest