If last year brought us extravagant chef cookbooks—lavishly illustrated works that belonged as rightfully on a living room coffee table as they did in the kitchen—this fall’s offerings could just as easily earn a place on the bedroom nightstand. Combining recipes with vivid autobiography, John Besh’s My New Orleans: The Cookbook (Andrews McMeel Publishing; $45), Michael Psilakis’s How to Roast a Lamb: New Greek Classic Cooking (Little, Brown and Company; $35), and David Chang’s Momofuku (Clarkson Potter/Publishers; $40) all use food as the organizing principle for their very personal stories. But each chef has his own individual reasons for breaking with the time-honored cookbook format of introduction, headnotes, and recipes. And it’s the trio’s varying expressions of elation, sadness, and intense commitment that elevate their works from a collection of ingredients and measurements to their measure as men.

In the case of Besh, the owner and executive chef of Restaurant August, who grew up in Slidell, Louisiana, his life of late has been molded by the sobering experience of living through Hurricane Katrina. In fact, the natural disaster is presented as a midlife wake-up call, transforming the gun-toting ex-marine who set up field kitchens to feed evacuees, refugees, and relief workers into a 24/7 preservationist obsessed with using local ingredients that have, as he puts it, “the flavor of here.” “After Katrina,” Besh writes in his book, “being from New Orleans became the focus of my identity.” And his born-again status seeps into everything: He returned to a more elemental style of cooking at his four Louisiana restaurants, and his latest cookbook is a vehicle not just to explain the pleasures of cornmeal-fried okra but to give context to classic New Orleans dishes by sharing boyhood anecdotes of making gumbo with freshly hunted wild blue-winged teal and preserving Celeste figs with his granddaddy.

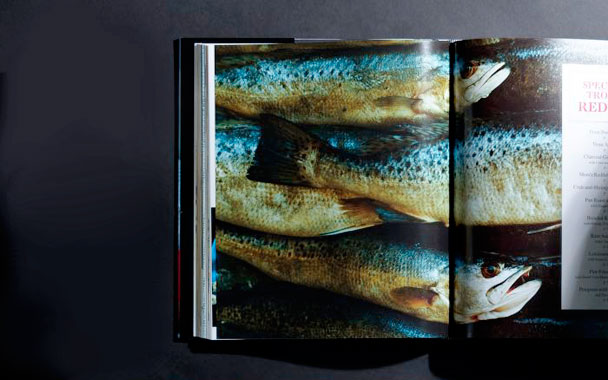

“Until you understand the roots of a cuisine, it’s hard to cook it with any sort of authenticity,” Besh said when I asked him how he thought the autobiographical portions of My New Orleans informed the recipes. “But once you understand the context, then you can use the recipe as a guide because so much of this food is very forgiving.” To this end, Besh structured the book chronologically into what he calls “micro-seasons” of ingredient freshness, which spurred him to insist that all the food in My New Orleans be photographed only when in season rather than shipped in from elsewhere to meet a shorter book-prep window. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall when Besh told his publisher he’d need a calendar year to get the art ready.

Manhattan head chef and restaurant co-owner Michael Psilakis also uses childhood memories to directly connect ritual, custom, and food. But his galvanizing incident, the event that drove him to write How to Roast a Lamb, was the death of his father, Gus, in 2007. Psilakis’s narrative unfolds on Long Island, where he was brought up by parents who immigrated—his father from the island of Crete, his mother from Kalamata—to the United States in the 1950s and raised their children in what Psilakis calls “a Greek bubble.” By this, Psilakis means that his parents built a tiny re-creation of their homeland in a middle-class suburb. On Psilakis’s first day of kindergarten, he stands out from the other five-year-olds in two ways: He’s dressed old-country style—a suit, dress shoes, and black socks—and he can’t speak a single word of English. But what also separates him is his culinary education, which is well under way: He has already prepared tiropitas with his mother and will later hunt for rabbits with the Psilakis men. And his father, who was herding sheep by the age of seven, is raising him to understand that a poor person’s connection to food is complex and not just about sustenance. “What mattered was that you were part of a family,” Psilakis told me. “You had a responsibility. If everybody did what their responsibility was, then they had food to eat. If they had food to eat, they were able to come together. And when they were able to come together, life was good.”

Everything about Psilakis, including his path to owning Anthos, the only Greek restaurant in the United States to receive a Michelin star, speaks to his fervid sense of filial duty. It began at T.G.I. Friday’s, of all places, where he found that waiting on tables and asking “Would you like an order of potato skins with that?” brought up unexpected feelings. “I felt like somehow I’d fallen into my own home,” Psilakis told me. “There wasn’t a weekend that went by that we didn’t have twenty or thirty people over and food was the center point of everything. As the oldest son, I was responsible for making sure that everybody had mezedes and drinks. It was my responsibility as people came in to welcome them and get them something. That’s how my whole life evolved.” So while the penultimate chapter of How to Roast a Lamb dedicates itself to Anthos and contains some of the restaurant’s trickier, updated spins on Greek classics, Psilakis (who is self-taught, unlike Besh and Chang, both of whom received formal training at culinary institutes) mostly walks the reader through food his housewife mother would prepare for their Saturday impromptu banquets. He sees How to Roast a Lamb as his opportunity to ennoble an entire ethnic community, and he isn’t about to squander it. “I’ve spent the last five years trying to get writers to write about Greek food,” said Psilakis, who is also head chef and co-owner of three other restaurants besides Anthos: Kefi, Mia Dona, and Gus & Gabriel. “When I first started, no one from GOURMET was calling me, you know what I mean? This book was a way for me to explain to people about the beauty of Greek food.”

Like Psilakis, David Chang is the son of immigrant parents. (His father is from northern Korea, his mother from southern.) But the best parts of New York City–based Chang’s tale are contemporary—from 2000 to the present—as he tells the story of going from a kitchen grunt who dreams of opening his own ramen shop to becoming the owner of four critically acclaimed restaurants: Momofuku Noodle Bar, Momofuku Ssäm Bar, Momofuku Ko, and Momofuku Bakery & Milk Bar. Chang’s rocket-like ascent has been well documented in magazines and newspapers, but because his coauthor, former New York Times food writer Peter Meehan, captures Chang’s obscenity-laden and hilariously tormented voice so perfectly, Momofuku still feels fresh. From Chang and Meehan’s perspective, Momofuku isn’t a typical memoir anyway (“To me, my take on a memoir is, it’s written from a leather armchair with scores settled,” said Meehan) or even a culinary instruction manual. Instead, it is a stringently honest record—tracked ingredient by ingredient—of how cooking the pan-Asian food he and his team found exciting was what ultimately allowed him to transform his first tiny East Village storefront from (his words) “a sh—y noodle bar” into a mini-empire. Chang portrays himself as a moody half-wit whom fortune has somehow smiled upon. His focus is entirely micro: He lives and dies with every plate of food he serves. What he’s undone by is the big picture, the whole chef superstar thing, which he finds presumptuous and embarrassing. “It’s almost premature to write a cookbook after a little over five years, but we wanted to sort of document it while it was all still fresh,” Chang told me, almost apologetically. Then he added, glumly, “Who knows? This could all come crumbling down next year.”

The historical document approach makes more sense when it comes to the recipes in Momofuku, which are really just versions of what Chang’s kitchen staff would use, only shrunken. Since it calls for things like five cups of rendered pork fat, I’m not sure that anyone expects the amateur cook to even attempt some of these dishes. (When I asked Chang, who is a bachelor and admits he never cooks for himself at home, about this, he moaned, “I don’t know. I kept on saying to Pete, ‘I don’t know who the f— is going to cook this sh— …’”) What Chang would probably shudder to know is that of the three books, his is the most inspirational because his stinging belly-flops are always followed by dogged perseverance and eventual victory. And the truth is that those willing to take a stab at his recipes will probably end up with a very close approximation of the food at his restaurants.

In a way, the lives of all chef-restaurateurs are the same: the long hours, the insufferable heat, and the endless pressure of running a business whose odds of success are against you. What distinguishes these books, therefore, are the personal motivations laid out between the recipes: Chang’s scrappy integrity, Besh’s commitment to his battered city, and Psilakis’s desire to honor his parents’ way of life. More than the stuff of memoir, they are what keep these dedicated chefs’ celebrated kitchens humming.

- Selected recipes: (registration required)

- Crab-And-Shrimp-Stuffed Flounder (Web-exclusive)

- Grilled Oysters with Spicy Garlic Butter(Web-exclusive)

- Pasta Milanese (Web-exclusive)

- Mudrica (Web-exclusive)

- Besh Barbecue Shrimp (Web-exclusive)

- Cucumber Kimchi (Web-exclusive)

- Sweet and Sour Eggplant and Onion Stew (Web-exclusive)

Pinterest

Pinterest