Full o’ th’ milk of human kindness” is how Shakespeare describes one of his leading men, but it is a better description of Lou DiPalo. Lou is the proprietor and genius loci of DiPalo’s Fine Foods, a 97-year-old latteria, or milk store, that has grown into a cheese and Italian specialty foods shop (the world’s greatest in my opinion) on the corner of Mott and Grand streets, in what used to be Manhattan’s Little Italy (but is now Chinatown). Lou’s face is equal parts kindness, tiredness, and boyish animation. Milk is his lifeblood. On occasion, when he looks pale and weary, after a night driving a delivery truck and a long day spent behind the counter, I imagine that milk is actually running in his veins. It is whole milk from happy cows, unhomogenized, warm, full of caseins (proteins essential to the production of cheese)—and it is what keeps him going, seven days a week, working the kinds of hours that would wear out somebody with mere hemoglobin to rely on. “We sell three hundred Italian cheeses,” Lou told me recently. “We counted them one day, my brother and me, and when we were done we said, ‘We are out of our minds.’ ”

Twelve years ago, I moved into an apartment four blocks from DiPalo’s and became a regular customer. Later, Lou and I became friends. I discovered that Lou likes to talk. He is fond of the soliloquy. He will explain what different cows were eating and metabolizing when they were milked—either spring flowers or intense first-growth summer grass or delicate autumnal second-growth grass or winter hay—and how cheese can contain whole landscapes and traditions in its flavor, color, and texture. “I talk too much,” he admitted recently, and I planned to protest, but he decided to elaborate. “I want you to taste everything. Before I sell it to you I have to share it with you. The shop’s an extension of my home. The counter is my dining room table.”

DiPalo’s is a warm, raucous, multigenerational family dining table. Lou’s late father, Sam, designed the store logo, which Lou describes as “a happy cow, giving a little wink. The mouth is a little squashed, but that’s because it’s supposed to be up against the window to give you a kiss.” It is a fantastical sort of place. And Lou DiPalo is, in a way, a fictional character—his real name is Luigi Santomauro, as was his grandfather’s. When the original Luigi, with his wife, Concetta, first opened the latteria, there was already a Santomauro’s on the block, so they put Concetta’s maiden name on the sign instead. DiPalo stuck, and Lou, like his father before him, still uses it professionally. Compromise became a culinary institution.

Last summer, I asked Lou if he thought there was any part of Italy in need of discovery.

Without hesitation he replied, “Trentino-Alto Adige, in the very north. It’s the bridge between the Mediterranean and Germanic and Austrian northern Europe. The people act like they’re not Italians, but they love being Italian.” Coincidentally, my favorite cheese is Crucolo, a semisoft cow’s-milk product, riddled with holes (Lou calls this “eye formation”), that is made by a family in Trentino’s Valsugana Valley.

“Do you mountain climb?” Lou asked. “Do you want to spend the night on a glacier? I can put together some wine and cheese and speck people, suggest some unvisited places, maybe find you a mountain guide.”

He was serious, I knew, but then he completely surprised me: “If you want, I could come with you.”

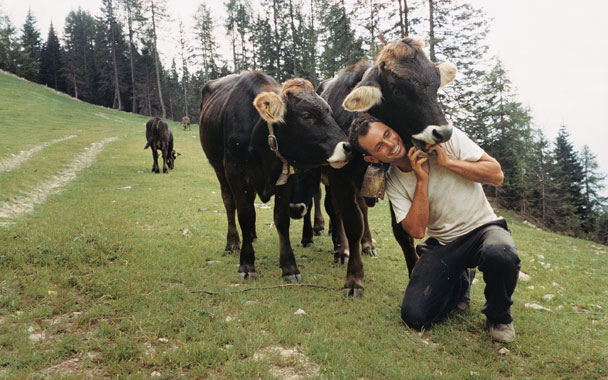

Since Lou’s is a magical reality, everything fell into place. My wife, Daphne Beal, and our son, Owen, came along, and in the middle of July we met Lou in Merano, a small town in the northern part of the region. Thirty minutes later we were on a gondola heading up a mountain. It dropped us off in a pasture, where we followed hand-lettered signs pointing toward lunch. A path took us through high meadows where the bells of brown and gray cows rang like wind chimes. There were no fences. Walking right up close to these cows, Lou explained their bells in much the same way he explains cheese in his store: “These are bruno alpina and grigio alpina cows, and their bells differ in size according to their value and importance. The head cow, the one that leads all the others up the mountain in the spring and back down in the autumn, will have the largest and most elaborate bell and collar.” From then on, every time we spotted cows—and they were everywhere—Lou slowed down, hopefully, trying to spot the leader’s bell.

“Alto Adige,” like “Lou DiPalo,” is an alias—after World War I, just before Concetta and Luigi Santomauro were getting their latteria going on Mott Street, South Tyrol, then part of Austria, was ceded to Italy and renamed Alto Adige. Most locals speak German and call the region what it has always been called, Südtirol. All the towns in the area have Italian and German names on their signs. Depending on how close you are to the border, the German name will come first.

After seeing cows and admiring their bells, we were hungry for cheese, so we visited a man who describes himself as a “cheese caretaker.” Hansi Baumgartner ages and refines cheeses in a Mussolini-era decommissioned bunker deep in the woods near the Brenner Pass, and sells them in a beautiful store and tasting room in Varna (a.k.a. Vahrn). All the milk in Hansi’s cow’s-milk cheeses is raw and comes from the Pinzgau breed, which is brown with a white stripe down the back and produces a small amount of milk with a high percentage of caseins. This is a cheese cow par excellence.

Pinterest

Pinterest