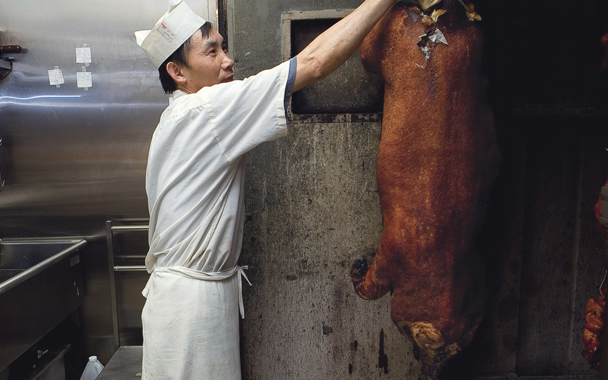

Behind me came the clack of the oven latch, a rush of scorching air, and then the rolling grumble of metal track as Si-fu hauled out 80 sizzling pounds of hot pig swinging from a hook. He twirled it around like a dance partner, eyeing its skin carefully for bubbles threatening to form. I looked hard. I couldn’t see what he was searching for, but I knew they had to be found: If they appear early in the roasting, they will puff, burst, and burn. He tapped the skin with carpenter’s nails, piercing it just enough to release pressure but not enough to let the juices escape. He threw arcs of salt as if casting rice at newlyweds and sent the pig back into the oven.

As I broke down barbecued ducks, smelling richly of fat and five-spice, Si-fu concentrated on the nearly inaudible crackle coming from the oven, waiting for the pitch that would tell him it was time to take another look. I heard the clack of the latch again, the grumbling of the rail, the tack-tack-tack of nails, the scratch of steel wool scraping at too-dark skin, the rustle of a basting brush. Over and over I would hear these sounds when he worked the pig, for hours at a time, breathing in thick heat.

I’d been working with Si-fu for a week at Ho Ho BBQ, a tiny shop in a nondescript strip mall in suburban Toronto, learning how to roast meats in the Cantonese style. It was work that was supposed to be steeped, for me, in flavors of childhood, in memories of Chinatown walks with my parents. But charming memories don’t get you very far when you’re pushing around carcasses hanging like heavy bags in a boxing gym.

The pig was done. It was a good one, meaning that the bubbles were all trapped inside the skin, making it crackly but also incredibly light, with a texture like Rice Krispies. It threw its heat around the room as Si-fu took a breath and hoisted, squeezing his bony frame through the narrow shop toward a display case. Ideally, he would have waited for it to rest, but the customers were wild-eyed and he came back to it with a big blade and intention. He knelt, only this wasn’t a devotional act. He performed an awkward upward stroke with grace, cleaving one half from the backbone, and began cutting off customers’ orders. The knife sailed through meat and skin, making a sound like walking on potato chips.

After the rush, he cut me a piece and I saw what all the work was for: crisp yet dissolving skin, tender meat, and lush, velvety fat. Textures in perfect balance and contrast. The flavor, too: Earlier, Si-fu had me cure the splayed-open pigs, massaging them with fistfuls of salt and sugar until the carcasses looked like snow at the moment you realize there’ll be no school tomorrow. The cure has only a few hours to penetrate, giving each bite a heavily seasoned side and a clean, juicy side. The flavor was sweet, salty, complex, and then mild and pure, as fascinating as it was delicious. Si-fu looked at me. “Quality,” he said.

When I was a kid, I’d ditch the TV and run to help my mother on the nights she brought home a Styrofoam box from Chinatown. Inside there would be duck like this, pork like this; half of it would be gone before the rice was cooked. It always felt like some kind of reward, but later I realized that it wasn’t about me. It was about convenience. It was about being cheap and easy for Mom.

But the taste of that barbecue is mostly a memory. The places my mother used to go to have all either gone away or gone downhill. One night a few months ago, my great-uncle shook his head as we left Ho Ho. “It doesn’t taste this good anywhere else anymore,” he said. He talked about China as it was a half century ago, a place where everyone knew how to roast ducks so that they were as rich as these, how to roast pigs so that they were as crisp as these. I am never careful enough around nostalgists. I went back inside and asked Jacques Wong, the owner, to let me work with him for a while. He said yes so casually I didn’t think he meant it. Then he said, “You know, it gets hot in here.”

I learned a lot cooking at Ho Ho, but maybe most of all this: Whatever it was for Mom, none of this is easy. Not learning to see invisible bubbles or hear inaudible noises. Not standing in the heat of an oven twice the size of a refrigerator. Not butchering and butterflying whole animals. Not scalding ducks and pigs with heavy kettles of boiling water to tighten up their skins. Not hoisting pigs up the stairs, your knee hitting the backs of their heads and them hitting you right back. But Jacques Wong has been doing these things nearly every day for almost 30 years, the last 10 in this shop. I called him Si-fu, Cantonese for “master,” at first out of convention, then quickly out of genuine respect.

Quality was the first thing Si-fu talked about when I arrived at Ho Ho BBQ. It’s an idea that has a grip on him. He insists on buying nothing less than the best ingredients, on doing things the hard way, the right way. He tells me about the steps others will skip, the cheaper meats others use. But he is fixated on quality, and I suspect it’s because his skills did not come to him easily.

When Si-fu fled China for Hong Kong, he learned to cook from chefs who kept secrets. For years, he plied them with food and drinks in return for lessons, sometimes spending a fifth of his meager pay. A sated cook would show him how to marinate meat; a hungry one would send him scurrying to scrub ovens. There was no complaint in his voice when he told me this, but he also said: “Of course, you have to end up better than your si-fu. You have to take what they teach you and add to it.” His dedication to technique, to quality, is fueled by a fierce pride.

Customers came in spurts, and in the slower hours Si-fu had time to chat with them, handing out extra tidbits—a hock here, pieces of tofu there. Earlier I had watched him drop blocks of that tofu into the fryer with speed, showering his arms with hot fat. Now he’s just giving it away. A regular came in for some bright red cha siu pork and offered Si-fu a lemon cake she’d baked. Si-fu cut himself a slice and urged others to do the same. “You should try some,” he said to a customer who claimed not to like Western sweets. “You don’t have to eat it if you don’t like it. But you should taste someone else’s culture.” He offered to buy coffee for his staff, to go with the cake, and reached into a Styrofoam cup he keeps filled with cash for just this purpose. He reached in again for a little more to buy a lottery ticket.

Pinterest

Pinterest