Every chef in the world has a story about the terrible things that happened when he or she was starting out as an apprentice. Gather a group of them together, and when they’re not talking about food, they’re telling tales of what horrors befell them in their first kitchens. The worse, the better: It’s a badge of honor. So when Citymeals-on-Wheels reunited the legendary chefs of France with the first American chefs who worked with them, the stories never stopped. André Daguin, Louis Outhier, Jacques Maximin, Georges Blanc, and Gaston LeNôtre are among the men who changed the way France ate and then exported the revolution by training an entire generation of young Americans, including Tom Colicchio, Charlie Palmer, and Nancy Silverton. For one star-studded night last June, they went back in time to re-create the dishes that made them famous. It was an act of generosity, a way to raise money to feed the less fortunate. But it was more than that: Behindthe scenes, the clock had been turned back, and some of America’s most honored chefs were once again apprentices, taking orders—and learning life lessons—from their mentors.

Tom Colicchio

“André Daguin was very impressive, a very big guy. He was a rugby player. When he came into the kitchen, you kept your head down. This was not a guy to be messed with.”

André Daguin

“The young chefs are better than us. And we are better than our fathers.”

Jean Banchet

“I don’t think one protégé is upset with me. I was tough. I made them cry. Roland Passot got a slap in the face from me. We are good friends.”

Roland Passot

“Banchet once threw a lamb saddle right out of the oven into my face. He should give me one of his Ferraris for that.”

André Soltner

“I didn’t like a lot of noise in the kitchen. When we worked, I liked it when everyone was calm. We had good relationships; otherwise, we wouldn’t have stayed together for ten, fifteen years.”

Pierre Gagnaire

“The legends all have the same sort of professional history: We started very young, worked hard, apprenticed with rough chefs. It makes me smile to be among these legends, because at the moment I don’t feel like I’ve done anything.”

Jean-Georges Vongerichten

“Outhier had a very happy kitchen, but nothing in the kitchen. Nothing on the stove. Every dish had to start from scratch.”

Joachim Splichal

“It was crazy yesterday when Maximin and I worked together to prepare for this event. He thought I had never left. That I was still twenty-three years old.”

Jacques Torres

“Maximin would say, ‘Let’s do desserts but not put the sauce around; instead, let’s put it inside.’ If I told him something wasn’t possible technically, he said, ‘I don’t care. Make it work.’ I learned, and when I moved on to Le Cirque, I did things like that.”

Jacques Maximin

“Working with those young chefs gave me a shock I’ll remember all my life.”

Georges Blanc

“Daniel Boulud worked with me for two years in the seventies. I think he’s a good cook, but he also has other qualities: civility, friendship. He’s very honest and humble.”

Daniel Boulud

“At Georges Blanc, I never worked with so many females in the kitchen or in the front. All the waitresses were beautiful, so it was paradise for me.”

Michel Richard

“When LeNôtre opened in New York, I came to this country. My dream was to learn English. The first thing I learned was Spanish: ‘Por favor,’ ‘Señor, rapido!’ That’s what you learn in a New York kitchen. I decided to stay more than one year because my English was so bad. Thirty-four years later I’m still here, and my English still isn’t so good.”

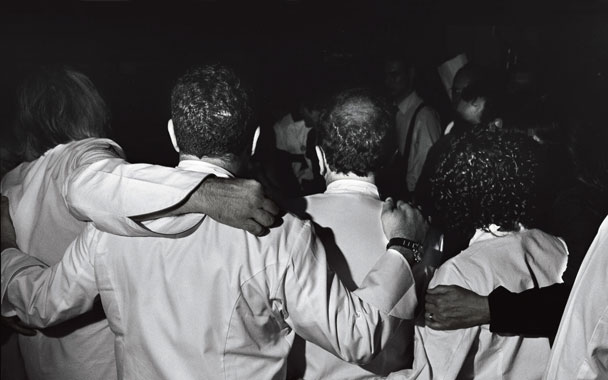

June 16, 2008, Rockefeller Center, New York City. “Going to an event where I’m the young upstart is just so neat,” said Tom Colicchio. He sounded earnest and naïve—nothing like the growling meanie of Top Chef. He added, “You know, these are the guys we all looked up to. The books that we bought were their books. Georges Blanc’s book was one of the first I owned.” He pointed toward the steps, where the French legends were busy posing for photographers. And then he rushed off to join the other American chefs, who were doing last-minute prep, each stopping now and then to take calls from the restaurants they left behind. “He wants a reservation for how many people? Tonight? Is there any way we can squeeze him in?”

The velvet ropes were removed and the paying guests poured in. Within moments, there was a line at the station where Jean-Georges Vongerichten was serving Louis Outhier’s classic oeufs au caviar. Outhier himself carefully topped each egg with a hefty spoonful of glistening black sturgeon eggs. “Caviar is like magic,” said Vongerichten. “You attract a lot of people when you open a can. It’s the only canned food people love.” Vongerichten put the finishing touches on his own caviar creation: egg yolks cooked slowly until they were practically molten, sandwiched between toast fingers, and then fried in butter and topped with caviar. Brilliant. Before the evening was over, the two chefs had gone through six kilos of caviar.

Pinterest

Pinterest