Peter Vestinos is standing in front of a mirror in the Westin Hotel in Long Beach, California, shaking an imaginary cocktail and trying to remember to smile. He mutters to himself as he scoops imaginary ice out of an imaginary bucket and pours it into a shaker, adds imaginary gin and imaginary grapefruit juice, and shakes. He contorts his mouth and tightens his lips, but the result is more of a grimace than anything else.

In three hours’ time, Vestinos will represent Chicago at the United States Bartenders’ Guild’s National Cocktail Competition. He’ll have seven minutes in which to make four identical drinks as a technical judge scrutinizes his every move. If he wins, it will be only the second time the underdog Chicago chapter has ever made it to the World Cocktail Competition. “Dammit!” he groans while making his phantom drink. He’s skipped a step—and he’s forgotten to smile. “I have a face that doesn’t naturally smile,” he says. “I’m a boy without a smile.”

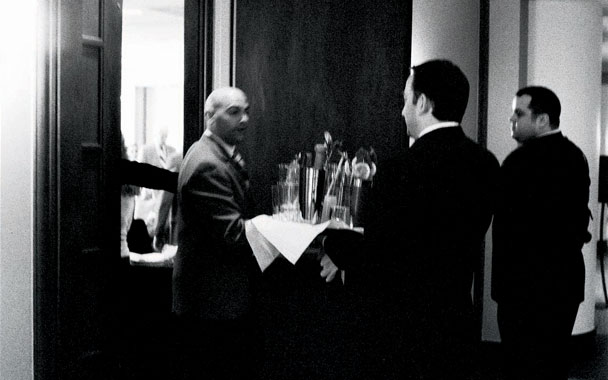

Ninety minutes later, Vestinos and his three competitors—who have made it to the nationals after defeating dozens of contestants in various regional competitions—are in the hallway the hotel has set aside for them as a prep area. Carlos Yturria, representing the Northern California chapter, isn’t smiling either. He’s pacing—and pausing every few minutes so he can sit down and hold his head in his hands. Among his supplies is a bottle of 106-proof Kübler absinthe, and he has recently only half-jokingly suggested, for the second time, that he and his three opponents do a shot.

“It’s all coming down right now,” he says.

For the past hour, Yturria, Vestinos, and their two other competitors have been feigning confidence. They’ve joked with each other, polished their glasses, and even started a betting pool on the Kentucky Derby. But as the competition approaches, the room grows quiet, and they all begin to show signs of fear.

“This is the nationals. The nationals, man! Are you kidding me? I’m sweating right now just thinking about it,” Yturria says. At which point the guys give in to the idea of a shot, and he begins tipping tequila into four wineglasses. Only Juan Alvarez, who’s representing Southern California, takes a pass. He’s up first, so he’s sticking to water. When a friend approaches and asks if he’s nervous, he doesn’t answer. He just sticks out his hands, which tremble violently.

It’s not just that these guys are competing at the nationals. This weekend also marks the 60th anniversary of the USBG. Roaming around the hotel with cigars in their fists are gray-haired men in red blazers, their lapels decorated with pins from competitions they’ve participated in over the decades. These are the old-timers, the ones who’ve been around since the organization started, as the California Bartenders Guild, in 1948. (It became the USBG in 1971.) They’ve watched as bartending morphed from respectable profession into scummy second job and back again. But as these veterans stand on the sidelines fingering their cigars, it’s clear that the USBG is changing all around them. Bartenders aren’t bartenders anymore; these young guys call themselves mixologists (see “The Mixologist’s Tale”). And they’re not even required to wear red jackets—the USBG recently voted to allow an alternative uniform of black suit, white shirt, and red, white, and blue tie.

Alvarez puts on a red jacket anyway and carries his tray into the competition room. The bar has been open for an hour, and the crowd is rowdy and impatient. Balancing the tray of glasses with garnishes and juice in one hand, he exhales dramatically. He looks like he’s going to cry, or maybe have a panic attack. But when he steps in front of the crowd, he starts to beam. His eyes sparkle. His teeth shine. When he presents the bottles to the audience, he could be a model on The Price Is Right. After six minutes, the technical judge announces that Alvarez has one minute left. But he’s golden: His cocktails have been poured, and all he has to do is add the garnishes. He finishes his final drink and lifts it in the air to present it to the judge. But his hand is trembling and the glass tilts, splashing some of it onto his hand. The crowd gasps, and Alvarez’s smile breaks. He knows he’ll get a deduction for the spill. But at least he’s done.

Pinterest

Pinterest