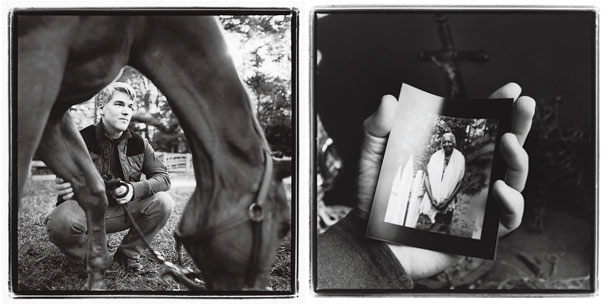

Scott Peacock is standing in a stable at the Vogt Riding Academy in Atlanta, talking lovingly about the horses lined up in their stalls. He has a half dozen apples in a Whole Foods bag, and the horses are peering out with interest. “Johnny is a very difficult horse,” he says, holding out an apple to one of them. “He’s bitten me, but it wasn’t bad, just a little bite on my leg.” Johnny snatches the apple, crunching it greedily between his huge teeth. “Isn’t he great? Would you like to feed him?” Thanks, no. “Look how they’re so beautiful. And it’s so peaceful here.” Peacock kisses Johnny on the nose and moves from stall to stall until the apples are gone. I have asked him to show me “his” Atlanta, the places that mean the most to him, and this is where he wanted to start. Peacock is the pride of the culinary South, and he is increasingly known as one of the finest chefs in the country. Watershed, the restaurant in suburban Decatur, Georgia, where he created a home-style menu of southern specialties emphasizing local ingredients, has been a popular and critical sensation since it opened nine years ago, and last year Peacock was named “Best Chef in the Southeast” at the James Beard awards. But the most important touchstone in his life is Edna Lewis, the great African-American chef who died in February 2006 at the age of 89. The two had been a devoted, mutually sustaining couple for years, cooking and traveling together and sharing a home. When she began to weaken and decline, he became her chief caregiver. During the last two years of her life, he spent nearly every hour with her when he wasn’t working; and in emergencies he jettisoned work, too. He was with her on the night she quietly reached the end, and a week later he put his name on the waiting list for riding lessons at Vogt.

The only other time he’d been on a horse, he says, was when he was eight years old. The neighbors kept horses—not unusual in Hartford, Alabama—and he liked imagining himself leaping onto a steed and riding off into a whole different childhood, preferably one designed by Norman Rockwell. “My parents loved me, but I wasn’t that typical child that comes out of a small town in Alabama in the ’60s,” he says, thinking about the Christmas he spent longing for his sister’s new Easy-Bake oven instead of all those tiresome toy trucks.

When his father at last brought home a pony, the little boy eagerly climbed on. A second later he was sprawled on the ground, and so was his dream of a childhood where he magically fit right in. The pony was a lemon, too mean for anyone to ride. Peacock clambered to his feet. “I’m sorry,” he told his father miserably. “It was my fault.”

Now he rides two or three times a week, and his favorite horse is the wary, unyielding Johnny. “There’s nothing easy about it,” he says. “There’s so much to work at, to get to that next level.” I don’t know whether he’s talking about riding or grieving. But when he describes his newfound relationship with these horses, it’s clear that he’s also thinking about the intertwined lives of a gay white man and a deeply reserved African-American woman nearly half a century his senior, whom he always calls “Miss Lewis.” He was talented but directionless when they met; she had a lifetime’s profound understanding of southern food. Her wisdom ignited his, and gradually they grew close in a way that neither of them had experienced before. “It’s about boundaries, about being aware and respectful,” he says. “It’s about being in constant communication back and forth. Those expressive eyes, the independence—I respect that. Miss Lewis was the first person that ever just saw and accepted me. She saw the good and the bad, and maybe she saw someone who could see her, too. This is what I learned from her: The power comes around when you are just being exactly who you are.”

He drives me through some of the lovely, leafy neighborhoods of Atlanta, pointing out the governor’s mansion, where he was the chef when he first met Edna Lewis, and talks about the bouts of depression that he struggled with for many years. “I did tons of therapy, I took tons of antidepressants,” he says. “I can remember turning the clocks to face the wall. I would erase the messages on the answering machine because I couldn’t face knowing they were there, waiting for me to answer. It was like wearing a lead suit. After all the doctors and all the tests and pills, the best it got was that it didn’t feel so bad to be in bed with the covers pulled up in a dark room.”

Pinterest

Pinterest