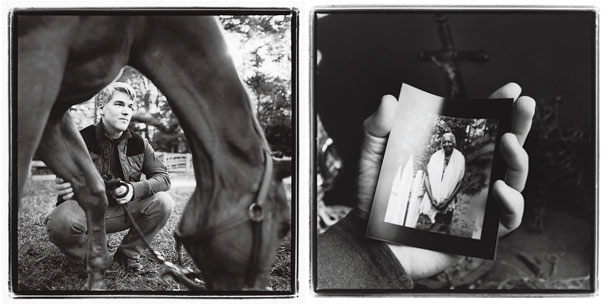

Scott Peacock is standing in a stable at the Vogt Riding Academy in Atlanta, talking lovingly about the horses lined up in their stalls. He has a half dozen apples in a Whole Foods bag, and the horses are peering out with interest. “Johnny is a very difficult horse,” he says, holding out an apple to one of them. “He’s bitten me, but it wasn’t bad, just a little bite on my leg.” Johnny snatches the apple, crunching it greedily between his huge teeth. “Isn’t he great? Would you like to feed him?” Thanks, no. “Look how they’re so beautiful. And it’s so peaceful here.” Peacock kisses Johnny on the nose and moves from stall to stall until the apples are gone. I have asked him to show me “his” Atlanta, the places that mean the most to him, and this is where he wanted to start. Peacock is the pride of the culinary South, and he is increasingly known as one of the finest chefs in the country. Watershed, the restaurant in suburban Decatur, Georgia, where he created a home-style menu of southern specialties emphasizing local ingredients, has been a popular and critical sensation since it opened nine years ago, and last year Peacock was named “Best Chef in the Southeast” at the James Beard awards. But the most important touchstone in his life is Edna Lewis, the great African-American chef who died in February 2006 at the age of 89. The two had been a devoted, mutually sustaining couple for years, cooking and traveling together and sharing a home. When she began to weaken and decline, he became her chief caregiver. During the last two years of her life, he spent nearly every hour with her when he wasn’t working; and in emergencies he jettisoned work, too. He was with her on the night she quietly reached the end, and a week later he put his name on the waiting list for riding lessons at Vogt.

The only other time he’d been on a horse, he says, was when he was eight years old. The neighbors kept horses—not unusual in Hartford, Alabama—and he liked imagining himself leaping onto a steed and riding off into a whole different childhood, preferably one designed by Norman Rockwell. “My parents loved me, but I wasn’t that typical child that comes out of a small town in Alabama in the ’60s,” he says, thinking about the Christmas he spent longing for his sister’s new Easy-Bake oven instead of all those tiresome toy trucks.

When his father at last brought home a pony, the little boy eagerly climbed on. A second later he was sprawled on the ground, and so was his dream of a childhood where he magically fit right in. The pony was a lemon, too mean for anyone to ride. Peacock clambered to his feet. “I’m sorry,” he told his father miserably. “It was my fault.”

Now he rides two or three times a week, and his favorite horse is the wary, unyielding Johnny. “There’s nothing easy about it,” he says. “There’s so much to work at, to get to that next level.” I don’t know whether he’s talking about riding or grieving. But when he describes his newfound relationship with these horses, it’s clear that he’s also thinking about the intertwined lives of a gay white man and a deeply reserved African-American woman nearly half a century his senior, whom he always calls “Miss Lewis.” He was talented but directionless when they met; she had a lifetime’s profound understanding of southern food. Her wisdom ignited his, and gradually they grew close in a way that neither of them had experienced before. “It’s about boundaries, about being aware and respectful,” he says. “It’s about being in constant communication back and forth. Those expressive eyes, the independence—I respect that. Miss Lewis was the first person that ever just saw and accepted me. She saw the good and the bad, and maybe she saw someone who could see her, too. This is what I learned from her: The power comes around when you are just being exactly who you are.”

He drives me through some of the lovely, leafy neighborhoods of Atlanta, pointing out the governor’s mansion, where he was the chef when he first met Edna Lewis, and talks about the bouts of depression that he struggled with for many years. “I did tons of therapy, I took tons of antidepressants,” he says. “I can remember turning the clocks to face the wall. I would erase the messages on the answering machine because I couldn’t face knowing they were there, waiting for me to answer. It was like wearing a lead suit. After all the doctors and all the tests and pills, the best it got was that it didn’t feel so bad to be in bed with the covers pulled up in a dark room.”

What wrenched him free of his demons was the sudden awareness that Miss Lewis had begun to grow frail. Her memory was wavering; more and more, she needed his help to get through the day. “I knew if I didn’t get up out of that bed, she was going to suffer,” he says. “If I screwed up and stopped working, what was going to happen? It was an amazing thing she gave me. I started showing up for her, and without realizing it I started showing up for me.” He says he hasn’t taken any medications in five years.

We reach the building where she lived before moving in with him. “There it is, 830 Greenwood Avenue,” he says, and shows me her first-floor window in the modest brick apartment house. Nearby, there’s a Thai restaurant where they often went, and we stop in for lunch. She always liked the coconut soup, so he orders that and takes a taste. “It’s not as good as it used to be,” he decides, but finishes it contentedly.

Sometimes Peacock sounds elegiac; often he expresses gratitude for all Lewis gave him. But whatever his mood, his sense of humor has a way of slipping to the forefront. (I won’t go into detail about the theme dinner he created for playwright Eve Ensler before a local performance of The Vagina Monologues, but he thoroughly enjoys describing the menu.)

That afternoon, we walk through the grounds and gardens of the Atlanta History Center, where years ago Peacock learned to cook in an open-hearth kitchen—flames and coals, cast-iron pots and pans, traditional recipes and local ingredients. It’s a kind of cooking he finds immensely satisfying, with no shortcuts allowed or even possible. When Miss Lewis turned 80, in 1996, he threw her a huge party and made everything in an open fireplace. He’s still proud that he was able to honor her so abundantly from his heart and hands.

We ended the day at Watershed, a sleek, airy restaurant in a former auto-repair shop, and he beams when the kitchen sends out the BLT salad—cool, immaculate iceberg lettuce, heirloom tomatoes, hefty slivers of a flavorful bacon, and square, toasty croutons, all tossed gently in a homemade mayonnaise.

Peacock is right: This could be the best salad in the world. His mother used to make it in a big Tupperware bowl, and he remembers eating the soggy, delicious leftovers from the refrigerator.

As he hunts down the last bits of lettuce on his plate, he says he’s ready now to move ahead. He wants to see Paris this year, he’s harboring a “semi-dream” of cooking in New York someday, and most of all he wants to finish writing the memoir he’s sweating over, about his relationship with Miss Lewis.

He has found that he writes best in a situation of controlled chaos—with the TV blaring, for instance, or in a busy café. Big chunks of his first book, The Gift of Southern Cooking, a virtual hymn to tranquil meals with friends that he co-wrote with Edna Lewis, were composed in Manhattan at a rackety Sbarro restaurant in Times Square.

More food comes out: Pimento cheese, grits with shrimp paste, fried okra, plum buckle—everything bursting with personality and clear, rich flavors. He had eaten these things all his life, but not until he met Miss Lewis did he start to take them seriously. “She is part of everything,” he says. “It is marvelous in a weird way, the dynamic relationship you have with someone who is dead. It continues to grow. I have a breathing, living relationship with her at this point.” He gazes affectionately at the food on the table, seeing beyond it. “I miss her incredibly. What helps is making biscuits.”