At a courtyard table one afternoon in Kunming, chef Li Yun thought for a moment when asked to define the cuisine of his native Yunnan province. Then he said, “Yunnan food has four characteristics. First is the sour flavor—mostly from vinegar, but also from local plants like sour pears and apples. Second is the chile flavor, la jiao, the hot red-pepper taste. Third is the pepper flavor.” By this, he meant ma-la, the numb-hot of Sichuan peppercorns. “Fourth is the sweet flavor, mostly from sugar. What sets Yunnan apart is the melding of the four. In other provinces, one flavor leads. In Shanghai, for example, it’s the sweet taste.”

I saw what he meant. In Hunan, it is the smoky flavor, in Sich-uan, the ma-la. True balance is an achievement. In Chinese cuisine, tiaowei, the combination of flavors, is an art in itself.

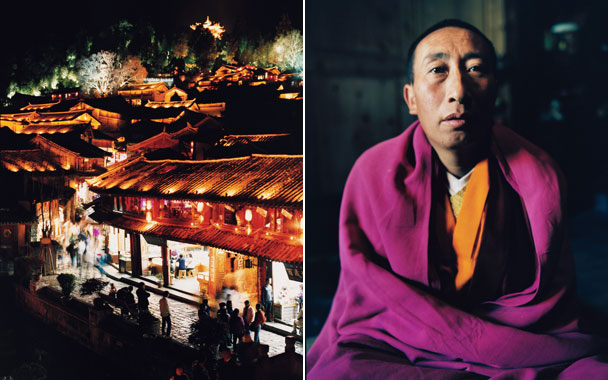

These days, food is a major draw for Yunnan’s tourists, most of whom come from within China. They come to see magnificent scenery and to experience the province’s dozens of intact minority cultures, but they also come to eat—especially vegetables. Tucked into China’s southwest corner between Laos, Myanmar, and Tibet, its dramatic terrain watered by the Mekong, the Salween, and the Yangtze, Yunnan boasts 18,000 plant species. Chinese diners know what that means. “While there, focus on the wild mushrooms, the vegetables,” advised Zhan Zhao, a lawyer friend from Beijing. “The food is great, all natural, vegetables picked fresh from the field every day.”

All Yunnan journeys start in the provincial capital, Kunming, where, luckily for the traveler, many of the region’s cuisines are represented. Unable to visit tropical Xishuangbanna, home of the Dai ethnic group, I compensated with a lunch at tiny Baita Daiwei Ting. Here the Dai classic gui ji, ghost chicken, turned out to be a showstopper of bright Southeast Asian flavors—tender shredded cold chicken dressed with lime, cilantro, ginger, garlic, and powerhouse quantities of hot chile. Boluo fan, fruit-fragrant black sticky rice served in a hollowed-out pineapple, made a cooling complement.

For fine dining, Kunming’s peak experience is Lao Fangzi (“Old House”), a two-story courtyard mansion, built in 1852, that teems with appreciative crowds. Here, as at other haute Kunming restaurants, chefs call their local style “Dian cuisine,” after the kingdom established in the area 2,300 years ago. There’s little sense of ethnic connection, just the desire to identify with antiquity—a recurrent theme in Chinese arts.

“Lao Fangzi’s most important aspect is the house itself,” said Li Yun, the chef. “We even cook with the roof tiles!”

What? I must have heard him wrong. “Roof tiles?”

“You cannot buy tiles like these! They are more than a hundred years old, high quality. Exposed to the elements. We roast beef, fish, and tofu on them.” Li, who has since left Lao Fangzi, said this line of dishes was so popular they bought up old tiles at demolition sites so as not to denude their own roof.

The tofu did indeed arrive on an ancient roof tile, and its taste was strange, half-fermented: the flavor of great age. Other house specialties were terrific, like the celestial salt-fried goose liver—thin, faintly crisp slices arranged on a bed of sautéed cilantro stems. And the “elephant tusk” ribs were cooked down to fall-apart leanness in a sauce so complex and balanced it brought chef Li’s four-flavor discourse to life.

Because I wanted to see as many of Yunnan’s diverse cultures as possible, I had decided to travel by the spine that bound them—the Tea and Horse Caravan Trail. This beaten-dirt route linked southern Yunnan to Lhasa from 618 to the 1950s. Along its way, cultures thrived, cities grew, and the story of life was written in each marketplace through trade, opera, and food.

By this road, I headed north. Dali, home to the populous Bai minority, promised gustatory wonders. Yet I alighted from my express bus and panicked. The Old Town was filled with tourists eating spaghetti and steaks. Where was the Bai cuisine?

Locals were happy to answer: at Yi Heng. From the street, this fine restaurant looked unremarkable, but a discreet door opened onto an elegant red-lanterned courtyard filled with the happy clamor of dining. Out front, as at all the area’s restaurants, a rack displayed the day’s astonishing assortment of unfamiliar vegetables. One of Yi Heng’s highlights is shaguo, a hearty clay-pot soup with a peppery fragrance. This regional classic is cooked in a pot, also called a shaguo, often cast from the earth of a particular village. And even if the prime ingredients vary, it never fails to teem with intriguing vegetables and thin-sliced Yunnan ham. Near Dali, shaguo fish and shaguo tofu are popular. In the Tibetan lands to the north, the great shaguo dishes are based on yak broth. Yet the very best dish I had in Yunnan was also the simplest—the humble, improbably delicious bean jelly. This revelation was first placed before me in a villager’s home in remote Shaxi County, north of Dali.

I’d gone up with a Bai driver to see Stone Treasure Mountain. Here, on a cloud-wreathed peak, grottoes filled with 1,000-year-old statues of Buddhist deities wait in silence. By some miracle, few visitors come. Hiking around the mountain was magic, but at twelve my driver raised the subject of lunch. This was natural: In China, office meetings can be cut off at twelve-ten even if they have but 15 minutes left to run. “You want to stop in Shaxi village, right?” he said. “My friends live there. Let’s eat at their house.”

Pinterest

Pinterest