At a courtyard table one afternoon in Kunming, chef Li Yun thought for a moment when asked to define the cuisine of his native Yunnan province. Then he said, “Yunnan food has four characteristics. First is the sour flavor—mostly from vinegar, but also from local plants like sour pears and apples. Second is the chile flavor, la jiao, the hot red-pepper taste. Third is the pepper flavor.” By this, he meant ma-la, the numb-hot of Sichuan peppercorns. “Fourth is the sweet flavor, mostly from sugar. What sets Yunnan apart is the melding of the four. In other provinces, one flavor leads. In Shanghai, for example, it’s the sweet taste.”

I saw what he meant. In Hunan, it is the smoky flavor, in Sich-uan, the ma-la. True balance is an achievement. In Chinese cuisine, tiaowei, the combination of flavors, is an art in itself.

These days, food is a major draw for Yunnan’s tourists, most of whom come from within China. They come to see magnificent scenery and to experience the province’s dozens of intact minority cultures, but they also come to eat—especially vegetables. Tucked into China’s southwest corner between Laos, Myanmar, and Tibet, its dramatic terrain watered by the Mekong, the Salween, and the Yangtze, Yunnan boasts 18,000 plant species. Chinese diners know what that means. “While there, focus on the wild mushrooms, the vegetables,” advised Zhan Zhao, a lawyer friend from Beijing. “The food is great, all natural, vegetables picked fresh from the field every day.”

All Yunnan journeys start in the provincial capital, Kunming, where, luckily for the traveler, many of the region’s cuisines are represented. Unable to visit tropical Xishuangbanna, home of the Dai ethnic group, I compensated with a lunch at tiny Baita Daiwei Ting. Here the Dai classic gui ji, ghost chicken, turned out to be a showstopper of bright Southeast Asian flavors—tender shredded cold chicken dressed with lime, cilantro, ginger, garlic, and powerhouse quantities of hot chile. Boluo fan, fruit-fragrant black sticky rice served in a hollowed-out pineapple, made a cooling complement.

For fine dining, Kunming’s peak experience is Lao Fangzi (“Old House”), a two-story courtyard mansion, built in 1852, that teems with appreciative crowds. Here, as at other haute Kunming restaurants, chefs call their local style “Dian cuisine,” after the kingdom established in the area 2,300 years ago. There’s little sense of ethnic connection, just the desire to identify with antiquity—a recurrent theme in Chinese arts.

“Lao Fangzi’s most important aspect is the house itself,” said Li Yun, the chef. “We even cook with the roof tiles!”

What? I must have heard him wrong. “Roof tiles?”

“You cannot buy tiles like these! They are more than a hundred years old, high quality. Exposed to the elements. We roast beef, fish, and tofu on them.” Li, who has since left Lao Fangzi, said this line of dishes was so popular they bought up old tiles at demolition sites so as not to denude their own roof.

The tofu did indeed arrive on an ancient roof tile, and its taste was strange, half-fermented: the flavor of great age. Other house specialties were terrific, like the celestial salt-fried goose liver—thin, faintly crisp slices arranged on a bed of sautéed cilantro stems. And the “elephant tusk” ribs were cooked down to fall-apart leanness in a sauce so complex and balanced it brought chef Li’s four-flavor discourse to life.

Because I wanted to see as many of Yunnan’s diverse cultures as possible, I had decided to travel by the spine that bound them—the Tea and Horse Caravan Trail. This beaten-dirt route linked southern Yunnan to Lhasa from 618 to the 1950s. Along its way, cultures thrived, cities grew, and the story of life was written in each marketplace through trade, opera, and food.

By this road, I headed north. Dali, home to the populous Bai minority, promised gustatory wonders. Yet I alighted from my express bus and panicked. The Old Town was filled with tourists eating spaghetti and steaks. Where was the Bai cuisine?

Locals were happy to answer: at Yi Heng. From the street, this fine restaurant looked unremarkable, but a discreet door opened onto an elegant red-lanterned courtyard filled with the happy clamor of dining. Out front, as at all the area’s restaurants, a rack displayed the day’s astonishing assortment of unfamiliar vegetables. One of Yi Heng’s highlights is shaguo, a hearty clay-pot soup with a peppery fragrance. This regional classic is cooked in a pot, also called a shaguo, often cast from the earth of a particular village. And even if the prime ingredients vary, it never fails to teem with intriguing vegetables and thin-sliced Yunnan ham. Near Dali, shaguo fish and shaguo tofu are popular. In the Tibetan lands to the north, the great shaguo dishes are based on yak broth. Yet the very best dish I had in Yunnan was also the simplest—the humble, improbably delicious bean jelly. This revelation was first placed before me in a villager’s home in remote Shaxi County, north of Dali.

I’d gone up with a Bai driver to see Stone Treasure Mountain. Here, on a cloud-wreathed peak, grottoes filled with 1,000-year-old statues of Buddhist deities wait in silence. By some miracle, few visitors come. Hiking around the mountain was magic, but at twelve my driver raised the subject of lunch. This was natural: In China, office meetings can be cut off at twelve-ten even if they have but 15 minutes left to run. “You want to stop in Shaxi village, right?” he said. “My friends live there. Let’s eat at their house.”

I’d read about Shaxi’s Sideng hamlet, which contains the last intact market square along the 2,175-mile caravan trail. Recently named one of the world’s “100 Most Endangered -Monuments” by the World Monument Fund, it was partially restored several years ago but feels unchanged, just as the muleteers left it. The merchant inn, the temple, and the opera stage still face the square, empty now but for trees and cobbles and piles of drying corn. Outside the village gates, the caravan trail is still a dirt track that winds between trees and over small stone bridges as it vanishes into the distance.

In the shady courtyard of the Ouyang family’s two-story carved-wood house, we had a fascinating vegetarian lunch. The star dish was a stir-fry of Yunnan’s celebrated wild mushrooms—but the platter of bean jelly was what set my head spinning. Thick-sliced and chewy-firm, it was a jelled bean starch reminiscent of Japan’s konnyaku and Korea’s dotorimuk. The Ouyangs topped it with an addictive chile-and-Sichuan-peppercorn sauce flecked with cilantro and crumbled peanuts. It was delicious, satisfying, and all but calorie-free.

I soon learned that bean jelly, now popping up on menus in Beijing and Shanghai, is a long-standing Yunnan favorite and a culinary signature of the caravan trail. Each trade center has not only its traditional toppings but its own local bean. In Dali it’s the wan dou, whose buttercup-colored jelly is often sliced into noodle shapes and called yellow bean noodle; in Lijiang, it’s the ji dou, which yields a jelly of gray green.

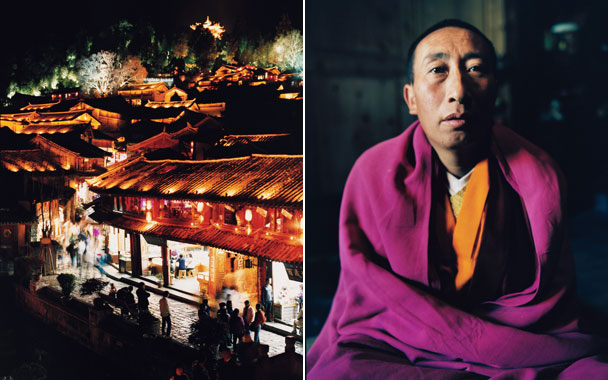

Through the centuries, when northbound caravans left Sideng hamlet by the trail, they traveled through mountain valleys and rhododendron forests to Lijiang. Now the journey is easy—I went by bus—and this ancient capital of the Naxi people has morphed into another magnet for visitors.

The Naxi have been in the Lijiang Valley for 1,400 years. They remain semimatriarchal, and in villages near Lijiang such as Baisha and Yuhu, their traditional lives can still be glimpsed, as women rake grain and men carry small children. In Yuhu, visitors can tour the home of Joseph Rock, the Austro-American botanist who gathered plant specimens, pioneered study of the pictographic Dongba language, and sent back thrilling reports via National Geographic. In one 1925 article he wrote, “I took with me my Siamese boy, the Tibetan cook and two Naxi servants.” And that was in addition to a gramophone, a collapsible bathtub, and ten Naxi soldiers, who sat around a fire at night firing off shots “to let marauders know that we meant business in case of attack.”

Nowadays popular excursions from Lijiang include cycle tours, ecotours, and my own favorite, the overnight trip to Lugu Lake, where the Mosuo people live in what some claim is the world’s last true matriarchy. Mosuo women never marry, but take such lovers as they please throughout their lives. They call their system zou hun, or walking marriage. At 13, each girl gets her own room with a box bed, a hearth, and a window to be opened for the man of her choice. Life at the lake today appears little changed from Joseph Rock’s 1920s photographs, on display in the main village. Yet as I watched dancers circle a bonfire to the music of a single wooden flute, I couldn’t help but think of something a man in Kunming had told me of this remote place: “In ten years, they will build a good road to Lugu Lake, and then that too will be gone.”

Even with options like these, most tourists stay in Lijiang’s Old Town. This district of cobbled streets with no cars and gorgeous Naxi architecture was restored after a 1996 earthquake with charm in mind. It’s crowded. It’s a bit ersatz. Yet the lovely buildings, gurgling streams, and majestic clouds scudding across the face of Jade Dragon Mountain more than compensate. And I liked seeing Naxi people in their own dress step through a circle dance, or set up a row of chairs to play traditional music—even if, as one Chinese man joked, they go home after eight hours and put their regular clothes back on.

Then there was the bean jelly. The vast vegetable market outside the Old Town was the place to eat it street-style, choosing from a mouth-tickling array of sauces and toppings. Every restaurant had it, and some places, like Haku Café, served it both cold and hot fried. I returned to this little place over and over, drawn by the good food and free Internet access, and by the home-away-from-home atmosphere. So delightful was the second-floor dining room, with its windows flung wide to the traditional rooftops, that I saw diners stay and play cards all evening, ordering coffees or drinks from the bar downstairs.

If Haku Café was the place to relax, Mishixiang Restaurant scored for group dining. After training in Guangzhou, chef Cun Yongheng returned with a full menu of excellent Naxi, Can-tonese, and Western dishes. He was one of several chefs to stress the Cantonese connection. Cantonese methods started to infiltrate local cuisine during the Second World War, when Yunnan became important to the Guomindang army as the Chinese terminus of the Burma Road. Chefs have always accompanied Chinese armies. By mid-century, Chiang Kai-shek was gone, but Cantonese techniques tending toward lightness, like steaming, stayed on.

In Lijiang I could also taste traces of the Tibetans, the next great ethnic group along the trail. Stalls sold dried yak meat, and vendors offered luscious yak skewers dusted with chile powder and cooked over charcoal. Once again cuisine was traveling the trail, announcing the world that lay ahead.

I followed these flavors north, stopping at a roadhouse for dried yak meat stir-fried with local vegetables I’d never seen before. The car crossed wall after wall of mountains and rimmed a gorge where the Yangtze, mighty with Himalayan snowmelt, thundered through narrow rock. Yet I noticed no terrain was too indomitable for China’s cellphone towers. These form the electronic caravan trail of today. Even in the most remote gorges my driver was fielding dinner invitations.

At 11,000 feet, the land opened to a high, arid plateau marked by wooden Tibetan farmhouses with their tufted racks of drying barley. Ahead I could see Zhongdian, recently renamed Shangri-La by the government to draw tourists. I was prepared for an edgy reaction—does anybody really believe James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon was inspired by this dusty trade-route outpost, as the Chinese authorities now claim?—but Zhongdian enchanted me. It was relaxed and genuinely friendly, with a frontier feel that at moments almost evoked the American West. Tibetan cowboys clattered down cobbled lanes on horseback, the 17th-century Songzanlin Monastery had a holy majesty, and the unrestored Old Town was just starting to sprout art studios and restaurants.

After I checked into my Tibetan-style hotel, a young woman named Droma stopped by to reconfirm my plane ticket back to Kunming. We started to talk and, in one of life’s unexpected gifts, kept talking for two days. There is a commonality in the lives of all women, everywhere, and few things are better than sharing it. As she told me of her life I slowly came to see that Droma herself was part of the caravan trail—or as the Tibetans call it, the gyalam, the “broad road.” She left her village, learned Chinese, then English; now she’s beginning French. She seeks the world, and it lies down that road.

At Songzanlin, we walked quietly among 700 monks in bright robes and the occasional, jolting pair of Western athletic shoes. Inside the prayer halls, yak-butter lamps flickered beneath serene Buddhas. Chanted prayers rose with smoke from sand vats of incense. Here was another force that had come by the road, the most powerful one yet: religion. In a whisper, Droma dissected the murals, then we climbed to the roof and spun the prayer cylinders. I have never felt so close to the sky.

By now I was obsessed with thoughts of how and when I could return—a sure sign I was falling for Yunnan. Yet I still didn’t grasp the full power of the caravan trail and its food—at least not until that night, when Droma took me to Arro Khampa! This restaurant at the top of a cobbled lane in the Old Town is run by three local Tibetans who went to India and returned, globalized. They see their restaurant as a culinary tribute to the gyalam, which changed their lives and the lives of their forefathers. An adventurous menu distills the three main Tibetan styles (Khampa, Lhasa, and Amdo) and reaches out along the road to the cuisines of China, India, and beyond. One chef is Nepalese. The lodgepole room with its warm fire is welcoming, the sound track is hip and multinational, and the yak-meat stir-fries are superb.

The next morning was hard. Would I ever have yak meat again? Or shaguo, or bean jelly? What about Droma? There was a knock on the door. Droma! “But it’s 7 a.m.”

“I woke the shopkeeper.” She held out a package, her warmth infectious. I took it, smiling with her. Before I even unwrapped the newspaper, as soon as I held it, I knew. I opened it. She had brought me a shaguo.