In Dublin, some things never change. The Celtic Tiger is still roaring, bringing unimagined prosperity to Ireland and its capital city. Day and night, limousines move slowly along the banks of the Liffey. Glittering new restaurants open every month, serving splendid food and wine to diners who, 15 years ago, would have been content with fish and chips. Cranes rise above the old rooftops, adding new office towers and new con-dominiums and new malls to a city where Jonathan Swift once issued his vehement bulletins. The good times proclaim their own triumph. The past, with its centuries of misery, seems at last to have vanished. And yet some things never change.

Begin with the rain. On my first day back, I leave the hotel, and the morning sky is bright. Eleven minutes later, a frail sunny rain is falling. Most Dubliners ignore it, as they have shrugged off rain since visiting Danes founded the city a thousand years ago. Dubliners now hug the walls, make quick calls on cellphones, light defiant cigarettes, and keep walking through the rain. A slight breeze rises, coming up the Liffey from Dublin Bay, and the rain falls harder. Umbrellas flop open. Ancient cobblestones glisten in Temple Bar. The bricks of the wonderful Georgian houses around Merrion Square are stained with rain. And then it abruptly ends. A few strangers look up, as if trying to decode the rushing clouds. Dubliners don’t look up.

“There’s not a damned thing you can do about it,” an old Dublin friend said to me one soggy morning. “You don’t come to Dublin for a tan.”

I’ve been coming to Dublin since 1963, and I have my routines of arrival. The first is to walk, since no city can truly be experienced by gazing out the window of a bus or a taxi. Dublin least of all. I want to see what is new. And I want to absorb again the presence of the familiar.

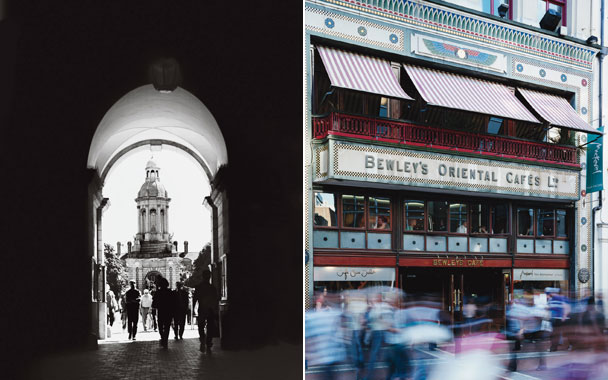

On this day, I head south along Westmoreland Street. Trinity College, established in 1592 by Elizabeth I, is soon to my left. As always, students, professors, and tourists are merging at the front gate, off to classes, lectures, libraries, or a glimpse of the Book of Kells in the extraordinary Long Room. Ancient, familiar Dublin whispers through the rain: Nothing has changed here since my last visit, except the faces; nothing will have changed the next time I pass this way.

The new narrative of Ireland shrugs off the past, with its nationalist furies, its endless tales of Irish martyrs, and speaks now about the glorious present and an even brighter future. But to my right, in the shadows of the 18th-century Bank of Ireland, I see a few of the casualties not often present in glowing tales of the Celtic Tiger. A scrawny beggar walks stone-eyed in the rain, silent, a thin hand extended. An occasional hurrying pedestrian presses a euro upon her. She doesn’t even nod. Various drifters huddle beside the massive columns of the bank, clothes ragged, devoid of either money or destination. People like these have been a part of Dublin life for centuries. Some wounds can’t be healed with money.

I cross College Green to a crowded but damp wedge of safety from the morning traffic. Grafton Street awaits me, that wide, sloping survivor of the early 18th century, where Yeats and Joyce and Beckett have all walked, where Percy Bysshe Shelley lived under British flags in 1812. These days I always pause first to gaze at the people clustered around the statue of the mythical Molly Malone, Dublin’s archetypal fishmonger, sung about in “Cockles and Mussels.” In all weathers someone is posing before—or upon—the statue of fair Molly with her abundant bronze breasts and her ancient cart. On this wet day, her shoulders and bosom are glistening with rain and four wet young Irish people are taking turns with three wet Japanese students to photograph her indomitable amplitude. Dubliners call the statue “the tart with the cart.”

Poor Molly Malone, involuntary sex symbol, is part of a cheerful unplanned archipelago of public statuary that has been subjected to traditional Dublin irreverence. On the north side of the Liffey near the Ha’penny Bridge, two bronze women sitting on a bronze bench with bronze shopping bags at their feet are called “the hags with the bags.” A statue of Anna Livia, goddess of the Liffey, sat for a long time in a fountain on O’Connell Street, water bubbling and gushing over her body. Poor Anna Livia became “the floo-zie in the Jacuzzi.” She was removed in 2002 to make way for a 394-foot silvery needle officially called “The Spire of Dublin,” expressing the soaring ambitions and accomplishments of Ireland as it entered the Millennium (two years late) in the boom years of the Celtic Tiger. The monument was instantly renamed by Dubliners “the spike,” slang for an addict’s hypodermic, in honor of O’Connell Street’s junkie population.

Grafton Street proper, once loud with the clip-clop of horses, and then the pealing of bicycle bells, and finally the rumble of cars, is now a pedestrian mall. It’s lined with department stores, music shops, ATMs, the windows full of clothing or appliances, books or iPods. As the rain abruptly ends, I pause in a doorway. Suddenly, buskers appear as if sprouting from the pavement: jugglers, musicians, a mime. The musicians are at once trying to earn lunch money and auditioning for passing agents who might give them their big break. Some of the performances are even good. Coins drop into hats. Photographs are taken. Then a black wind suddenly rises on this inconstant morning. The rain scatters everyone except the mime, whose makeup is apparently waterproof, and I turn left into Duke Street, heading for Dawson Street.

Pinterest

Pinterest