In Dublin, some things never change. The Celtic Tiger is still roaring, bringing unimagined prosperity to Ireland and its capital city. Day and night, limousines move slowly along the banks of the Liffey. Glittering new restaurants open every month, serving splendid food and wine to diners who, 15 years ago, would have been content with fish and chips. Cranes rise above the old rooftops, adding new office towers and new con-dominiums and new malls to a city where Jonathan Swift once issued his vehement bulletins. The good times proclaim their own triumph. The past, with its centuries of misery, seems at last to have vanished. And yet some things never change.

Begin with the rain. On my first day back, I leave the hotel, and the morning sky is bright. Eleven minutes later, a frail sunny rain is falling. Most Dubliners ignore it, as they have shrugged off rain since visiting Danes founded the city a thousand years ago. Dubliners now hug the walls, make quick calls on cellphones, light defiant cigarettes, and keep walking through the rain. A slight breeze rises, coming up the Liffey from Dublin Bay, and the rain falls harder. Umbrellas flop open. Ancient cobblestones glisten in Temple Bar. The bricks of the wonderful Georgian houses around Merrion Square are stained with rain. And then it abruptly ends. A few strangers look up, as if trying to decode the rushing clouds. Dubliners don’t look up.

“There’s not a damned thing you can do about it,” an old Dublin friend said to me one soggy morning. “You don’t come to Dublin for a tan.”

I’ve been coming to Dublin since 1963, and I have my routines of arrival. The first is to walk, since no city can truly be experienced by gazing out the window of a bus or a taxi. Dublin least of all. I want to see what is new. And I want to absorb again the presence of the familiar.

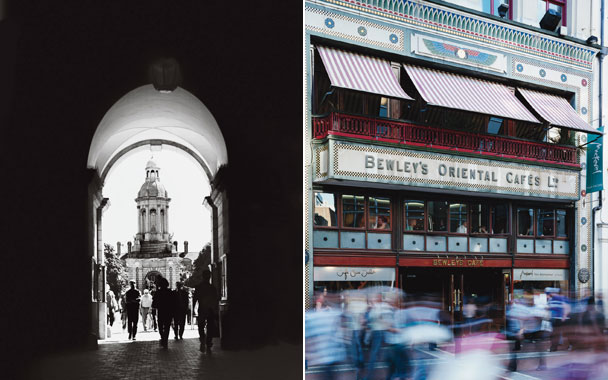

On this day, I head south along Westmoreland Street. Trinity College, established in 1592 by Elizabeth I, is soon to my left. As always, students, professors, and tourists are merging at the front gate, off to classes, lectures, libraries, or a glimpse of the Book of Kells in the extraordinary Long Room. Ancient, familiar Dublin whispers through the rain: Nothing has changed here since my last visit, except the faces; nothing will have changed the next time I pass this way.

The new narrative of Ireland shrugs off the past, with its nationalist furies, its endless tales of Irish martyrs, and speaks now about the glorious present and an even brighter future. But to my right, in the shadows of the 18th-century Bank of Ireland, I see a few of the casualties not often present in glowing tales of the Celtic Tiger. A scrawny beggar walks stone-eyed in the rain, silent, a thin hand extended. An occasional hurrying pedestrian presses a euro upon her. She doesn’t even nod. Various drifters huddle beside the massive columns of the bank, clothes ragged, devoid of either money or destination. People like these have been a part of Dublin life for centuries. Some wounds can’t be healed with money.

I cross College Green to a crowded but damp wedge of safety from the morning traffic. Grafton Street awaits me, that wide, sloping survivor of the early 18th century, where Yeats and Joyce and Beckett have all walked, where Percy Bysshe Shelley lived under British flags in 1812. These days I always pause first to gaze at the people clustered around the statue of the mythical Molly Malone, Dublin’s archetypal fishmonger, sung about in “Cockles and Mussels.” In all weathers someone is posing before—or upon—the statue of fair Molly with her abundant bronze breasts and her ancient cart. On this wet day, her shoulders and bosom are glistening with rain and four wet young Irish people are taking turns with three wet Japanese students to photograph her indomitable amplitude. Dubliners call the statue “the tart with the cart.”

Poor Molly Malone, involuntary sex symbol, is part of a cheerful unplanned archipelago of public statuary that has been subjected to traditional Dublin irreverence. On the north side of the Liffey near the Ha’penny Bridge, two bronze women sitting on a bronze bench with bronze shopping bags at their feet are called “the hags with the bags.” A statue of Anna Livia, goddess of the Liffey, sat for a long time in a fountain on O’Connell Street, water bubbling and gushing over her body. Poor Anna Livia became “the floo-zie in the Jacuzzi.” She was removed in 2002 to make way for a 394-foot silvery needle officially called “The Spire of Dublin,” expressing the soaring ambitions and accomplishments of Ireland as it entered the Millennium (two years late) in the boom years of the Celtic Tiger. The monument was instantly renamed by Dubliners “the spike,” slang for an addict’s hypodermic, in honor of O’Connell Street’s junkie population.

Grafton Street proper, once loud with the clip-clop of horses, and then the pealing of bicycle bells, and finally the rumble of cars, is now a pedestrian mall. It’s lined with department stores, music shops, ATMs, the windows full of clothing or appliances, books or iPods. As the rain abruptly ends, I pause in a doorway. Suddenly, buskers appear as if sprouting from the pavement: jugglers, musicians, a mime. The musicians are at once trying to earn lunch money and auditioning for passing agents who might give them their big break. Some of the performances are even good. Coins drop into hats. Photographs are taken. Then a black wind suddenly rises on this inconstant morning. The rain scatters everyone except the mime, whose makeup is apparently waterproof, and I turn left into Duke Street, heading for Dawson Street.

I pass the Bailey, where James Joyce did some drinking before leaving Ireland forever in 1912, and Davy Byrnes, where Leopold Bloom lunched on a Gorgonzola sandwich on June 16, 1904, in Ulysses. On that date each year the street is usually jammed with Joyce scholars and groupies, all of whom are subjected to various murmured forms of Dublin malice. The drinking and dining places date from the era when every Dublin pub was thick with blue fog from cigarettes—Player’s, Senior Service, Woodbine, Sweet Afton. These days, everybody seems to be smoking Marlboro Lights, and they are doing it out on the sidewalks or under umbrellas. Ireland has followed the example of New York and other cities in banning smoking from all bars and restaurants. The predicted violent revolutions never happened. Rain is dispersing the fumes as I hurry into Dawson Street.

It’s one of my favorite Dublin thoroughfares. Not because of the many restaurants, a few of them excellent. Not because of the elegant charm of the Mansion House, which is home to the city’s mayor, or the Victorian jumble of St. Anne’s Church. I rush hungrily to Hodges Figgis, one of the city’s finest bookshops. Like Dublin itself, there is never time to see everything at Hodges Figgis on a quick visit. As always, I stay an hour, planning to return (and always do). I pay for my treasures, which the cashier protects from the rain with plastic. Out on Dawson Street, the sun is shining brilliantly. Still, you never know.

Dublin, of course, is not a simple matter of bookstores or ancient streets and buildings rich with the patina of time. In a familiar city, an essential part of my own sense of familiarity is friends. We meet. We dine together. And, of course, we talk.

The talk always flows, and not because the Irish have, as the tedious stereotype goes, “the gift of the gab.” There are dour Irish people, and inarticulate ones, and people who would bore a tortoise. My friends are talkers. They talk about politics (foreign and domestic) and sports, theater, books, immigration, the woeful state of Irish hospitals, the traffic, the absurd cost of property, and, when asked, about life in today’s Dublin.

“It’s more violent,” said my friend John Boland, who writes television criticism for the Irish Independent and is an accomplished poet. “There’s a feeling in town that’s worse than it’s been in my lifetime.”

Crime is on everybody’s mind. What doth it profit a man if he gain a second car and has to look over his shoulder after dark? In fact, as the government and police struggle to deal with the new realities in a prosperous Ireland, crime rates are dropping. The most common Dublin crimes are “public order offences,” where, in the Irish phrase, “drink was taken.” This is part of the great change in pub culture. The days and nights of the Irish pub, smoky and dark and intimate, are giving way to another phenomenon: the superpub. These are immense places, loud with music; part honkytonk, part dance hall, some servicing as many as a thousand drinkers on several floors. As the Yeats line goes, this is no country for old men.

Many of the young men in the superpubs have the shaved skulls of British football fans or civilian contractors in Iraq. Some of them are down from Belfast for the weekend, or over from Liverpool, and, along with their Irish counterparts, are in pursuit of young Irish women or visiting Europeans and Asians. When the young men fail at romance, they often end up battering each other on the sidewalks. Watching them on a recent Saturday night in Temple Bar, I am happy to be old.

There is, however, a far more sinister aspect to Irish crime. Organized drug gangs are the dark side of the Celtic Tiger, a violent parody of the prevailing desire for instant wealth and power. Both dealers and customers are often bred in the bleak purgatory of public housing estates. You can see their scouts and outcasts along O’Connell Street, on the north side of the Liffey. They are almost never threats to tourists. But every month the corpses of the luckless are found in alleys or forests, killed by overdoses or a bullet in the head.

Some Dubliners blame recent immigrants for crime, often singling out Nigerians. “Those bloody Nigerians don’t care for anybody,” one taxi driver told me, blaming thousands of Nigerian immigrants for the crimes of a few. Nigerian criminals don’t run the drug trade, of course; it’s an Irish monopoly—but a few do commit burglaries, purse snatches, and identity thefts. This has led to a troubled debate among the Irish and to the tightening of immigration laws. Race is certainly central to the quarrel. But there are other Irish people who remember that in the not-too-distant past Irish immigrants in New York and England were often blamed for all local troubles. In those days, the Irish were characterized as dirty, lawless, congenitally criminal. In today’s Ireland, some of the same mindless stereotyping is present. Sometimes the discussion turns ugly.

“They should round them up,” I was told by one middle-aged carpenter, “and send them back where they came from. Dead or alive.”

An old, old song, but new to Ireland.

There isn’t enough time on a short trip for everything that Dublin now offers, but there are some essential treasures that seem even grander as the years go by. All of Georgian Dublin awaits the wanderer through Merrion Square and Fitzwilliam Square, causing the walker in the rain to wonder why the Irish ever chose to build in any other style. The National Gallery of Ireland has one of the few Vermeers in the world, plus a Caravaggio that was discovered in 1990 hidden away in a Jesuit residence. There are many Irish paintings in this museum, including works by Jack Yeats and William Orpen, that should be better known to the wider world.

On the northern side of the Liffey, O’Connell Street is less grungy than it was a few years ago, but it retains an aura of menace after dark. If you pause and talk to the drifters, you hear bitter complaints directed at other Irish people. “What do these gits know about anything real?” one man said. He was 30 and looked 50, and had gaps in his upper teeth. “They don’t get up and go for a job that’s gone for good. Lookit them, with their cars and computers and fancy food. What do they know?”

Still, the area around O’Connell Street contains many delights. There is always something worth seeing at the Abbey Theatre or the Gate, and I like the smaller museums devoted to James Joyce, other Irish writers, and the tale of the Jews in Ireland. They help a visitor set aside, at least for a while, the brooding sense of hurting resentment that darkens the bright portrait of the Celtic Tiger.

On every trip to Dublin, I make one essential stop, usually on my last day there: St. Patrick’s Cathedral. I come for one reason: From 1713 until his death in 1745, Jonathan Swift was its dean. For me, he represents the best of the Irish past, still vividly alive in the glittering present.

In the silence of the cathedral, I always thank Swift for Gulliver’s Travels, The Drapier’s Letters, A Modest Proposal—and for his many other writings, private and public. I thank him for the purity of his rage, his furies over poverty and Britain’s indifference to the suffering of its Irish subjects. I thank him for his advice to writers, that it is better to write with the point of the pen, not the feather.

Some of his writings are exhibited here, speaking to us across the centuries. “We have just enough religion to make us hate,” he wrote in 1728, “but not enough to make us love one another.” We are reminded that in his lifetime he raised funds to establish a residence for destitute women, and that when he died, he left the bulk of his fortune to build a hospital for the mentally ill. His acid wit, his armor of irony, did not erase his pity and compassion for the injured people of Dublin, and Ireland, and, by extension, the world. We know him now as an enemy of sham, hypocrisy, and bogus piety. No wonder that his voice resonates to this day.

I find my way, as always, to the place on the cathedral floor beneath which Swift is buried beside the woman known as Stella. All his biographers acknowledge that he was a man with deep flaws. To Stella (whose actual name was Esther Johnson) the flaws didn’t matter. They were together for many years, probably platonically, and never married. She died in 1728, and he outlived her by 17 years. But they remain together in the peace of St. Patrick’s forever.

As I leave the cathedral, a frail rain is falling. In the distance, past the Scissorhands Hair Studios and a convenience store, I can see part of the Liberties, which for centuries housed many of Dublin’s poorest citizens. Now the old orange-brick houses are being rehabbed, sold or rented to the prosperous young, while the poor are forced out by the power of money and progress. “Where am I supposed to go?” one old man says to me, his voice forlorn and bitter. “I was born here, and they’re t’rowing me out.” He is filled with indignation, and I think, as always, of Swift, who wrote his own epitaph in Latin (translated into English for visitors): “Here is laid the body of Jonathan Swift ... where fierce indignation can no longer rend the heart. Go, traveler, and imitate if you can, this earnest and dedicated champion of liberty.”

In this exuberant modern city, this European place of grand restaurants and computers and immense new fortunes, fierce indignation is not dead. Neither is the spirit of Jonathan Swift. In Dublin, some things never change.