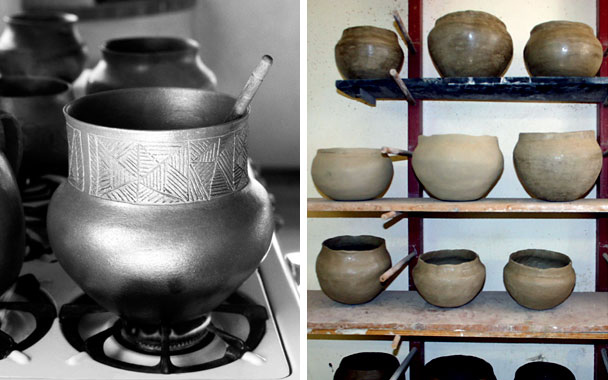

Just as chiles might be regarded as the iconic food of New Mexico, micaceous pots are the region’s iconic cookware. These utilitarian vessels have been made and used by Taos, Picuiris, Nambe, Tesuque, Jemez Jicarilla Apache, and other native peoples since well before these groups first had contact with the Spanish in the 1500s. And though cooking vessels aren’t usually thought of in this way, micaceous cookware is also, in some respects, an ingredient, for many people say that these pots impart a special flavor to foods cooked in them—and even improve the taste of water that has been stored within their sparkling walls.

Micaceous clay is a naturally occurring blend of mica and red clay, found in pockets in the mountainous areas that rise above New Mexico’s Rio Grande valley floor. I first encountered micaceous clay when I met Felipe Ortega, a Jicarilla Apache and medicine man who lives in La Madera. Ortega teaches pottery in Mexico, Santa Fe, and Switzerland, and I first made his acquaintance when he stepped away from a class to sign an enormous pot that he had made for my friend Hugh Fitzsimmons, who raises bison in South Texas. Suddenly Ortega turned to me and asked me how to spell my name. I knew that the pot was intended for Hugh’s wife, not for me, but for a greedy split second I hoped that this magnificent work—with its soft form and subtle shine—would be mine. I was smitten.

But it was another 15 years before I had a micaceous pot of my own. Now I can’t imagine cooking in anything else. I love the look and feel of the clay, softer than metal and lighter than cast iron. My micaceous pot gives off the scent of minerals and earth when heated, and it cooks foods evenly and beautifully. Many people swear that beans are tastier when cooked in micaceous clay, and Ortega suggests that it’s the combination of the acidic mica with the more alkaline clay that makes food taste so much better. “Sweet” is the word he uses. Not sweet as in sugary, but sweet as in balanced, as opposed to harsh or bitter.

Beans are the most common things to find simmering within the walls of micaceous pots, but you can cook pretty much anything in this clay. I have roasted Navajo-Churro lamb and made chicken fricassees, vegetable soups, beets, potatoes, braises, and any number of other dishes in my micaceous pots. I can’t really say with any kind of proof why these foods seem to taste better than if they were cooked in more conventional pots, but I know that I enjoy the process more—the light feel of the clay and the soft sounds utensils make when they come in contact with the rim of a pot. I also just like to have the pots out where I can see them, because their shapes and colors are so enjoyable to look at. In fact, it’s not unusual for people to buy micaceous pots at Santa Fe’s Indian Market, then put them on display and never use them at all.

But despite their delicate look, micaceous cooking pots are incredibly sturdy and utilitarian. My neighbor, Elisabeth Foote, has been studying with Ortega, and it is largely her pots that I use. When I hesitated to use my first pot, thinking it too fragile, she reassured me that it was plenty strong. “Do you know how hard it is to break up a pot that didn’t work out?” she asked. Pretty tough, apparently! Indeed, my pots take almost a daily turn on the stove and in the sink with no chips, cracks, or other ill effects.

Pinterest

Pinterest