We’re in a town where, our guide tells us, the women do all the work. The story goes that the women bring home the proverbial and literal bacon, and the men are supposed to demonstrate their prowess by getting fat, gambling and being bad ass mahjong hands. Immediately, I start hearing the jokes from my family about finding me a bride. Luckily, my brother is also here to absorb part of this punishment, and I’m free to wonder about the cultural sensitivity of these comments.

Lijiang, at the foot of Yulong Mountain, boasts two ancient cities: one destroyed by earthquake in 1996 and restored; the other, a UNESCO World Heritage site, intact for over 800 years. The latter is particularly stunning, built around a series of narrow canals of clear meltwater colored with fish.

Both of these are largely kept now as tourist sites, the old storefronts and residences essentially comprising massive souvenir malls. So I’m kind of disappointed, but also kind of conflicted about that disappointment. These people need to make a living, and I’m not really sure it’s ok for me to want them to make a living like they did 600 years ago just so my tourist experience isn’t like every other tourist experience. If you need to be selling me yak jerky so that you don’t have to live on yak jerky yourself, who am I to complain about it?

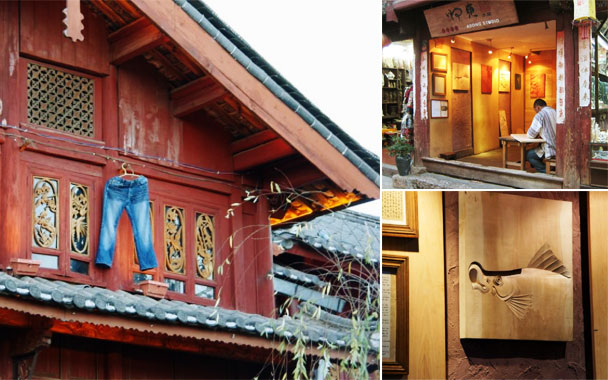

And so the streets, arresting as they are, are lined with yak jerky shops, along with silver, tea, herb, shawl, and various tchochke dealers, each indistinguishable from the last and without walls to separate them from the street. Unexpectedly, I came across a tiny, spare storefront with an intense-looking man sitting up against the street drawing on a piece of wood. The sign above his shop read “Adong Studio,” and his walls displayed a few of his woodcarvings. I walked in to look at them, finely made and thoughtful, introducing Picasso-like forms to traditional themes and working with the wood grain to accent the images.

The artist didn’t look up. On his wall, also, was his handwritten biography in English, detailing things like how he got his name, how his parents hoped for him to be a “moral person,” and how his father died when he was young. I started to feel a little awkward about the fact that we hadn’t addressed each other yet, even though I was looking at his art and reading about his life two feet from him. But he didn’t even look up at me, didn’t seem interested in talking, even as I stood watching him chip at his block.

Pinterest

Pinterest