I’ve been gazing, awestruck, at some of the famous-chef cookbooks that have appeared this season, trying to figure out what purpose they might serve in, say, my kitchen; and I finally realized my thinking was all wrong. Even the term “cookbook” is probably a stretch. These massive totems belong over in the Religion section of the bookstore. Or the shelf labeled Occult. Or maybe there’s a corner devoted to Irreproducible Results. Remember when celebrity chefs felt their grandeur could be adequately represented by cookbooks that were gigantic, over-designed, and completely impractical? Today that’s just the first draft. By the time a chef’s book is published nowadays it’s likely to have been pumped up to such a towering degree of self-congratulation and pomposity that its only conceivable function is to sit on a home altar swathed in incense.

Take a look—which is all you can do without a tow truck—at A Day at elBulli, by Ferran Adrià, Albert Adrià, and Juli Soler (Phaidon, 528 pages, $49.95). Food lovers who have always regretted not being present at the creation of the world will be happy to learn that at last they have a chance to watch an equally momentous event take place: the creation of a dinner by the inventor of techno-cuisine himself, Ferran Adrià. It’s certainly high time that the Chef of Chefs was featured in his own Bible, and this one honors him in a seven-pound volume dense with reverential photographs and written in the majestic intonations of a cosmic voice-over. First we see dawn breaking over land and sea (“06:05 Not every day is the same, but there are many like this....”), then the restaurant’s spectacular Catalan setting (“The site is 450 million years old and of great geological importance”), and then—oh, look, a humble figure is making his way along the road, lost in revery. Is it he? Yes, it is Ferran. We pause to study a sepia-tinged leaflet of family snapshots that’s been bound into the book (“The Early Years of Ferran Adrià”) before following the great one, moment by moment, through his entire day and evening. “Ferran tries different methods of slicing salsify.” “Later on, Ferran will check the order sheets.” “Ferran stands quietly as the Hallelujah Chorus breaks out around him.” Sorry, I must have imagined that last part.

Now peer into The Big Fat Duck Cookbook, by Heston Blumenthal (Bloomsbury, 530 pages, $250), but please don’t spill your coffee on the display copy. That price is not a misprint. Blumenthal, the British chef whose Fat Duck restaurant has won every award imaginable, has packaged his book in a hard, protective case—not really necessary for a volume printed on metallic-edge stock so thick you couldn’t damage it with a drill, but the message is clear: Book of Kells, you’re toast. Psychedelic art glitters on two-page spreads, some of them opening up into triptychs like medieval altarpieces—though, unaccountably, nobody’s added the little figures along the sides depicting contemporary food writers kneeling in adoration. An enthralled commentary on Blumenthal’s life, his culinary creations, and what he likes to call his “philosophy” has been provided by, well, Blumenthal, though he’s had to round up a few guest writers to make sure of doing the subject full justice.

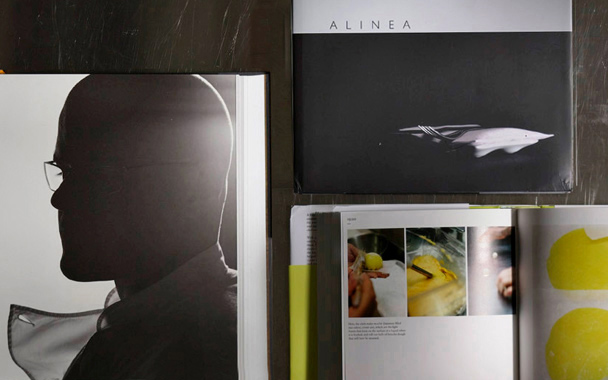

Guest writers also contribute to Alinea, by Grant Achatz (Ten Speed Press, 415 pages, $50). How else to convey the ineffable achievements of this Chicago restaurant except by summoning various devotees to record their pilgrimages? But when it comes to the most challenging aspects of the doctrine, chef Achatz himself takes over, ruminating on such concepts as “Profile Replication” and “Form Mimicking.” Occasionally his disciples quote him in passages that sound like excerpts from an audience with a Zen master.

After my meal, I asked Grant how he made the parsley sauce. He came back at me with the same question: ‘How would you make that sauce?’

‘That’s simple,’ I said. ‘I would take parsley and puree it with olive oil, let it sit for a while to infuse the flavor and color of the herb into the oil, and then strain it.’

Grant smiled. ‘Then you’d have parsley oil. It will taste like parsley and oil.’

It’s no accident that these particular books come from restaurants devoted to what I’ve termed “techno-cuisine” and others call “experimental” cuisine, or “hypermodern” cuisine. You know what I mean—food that’s been chemically processed and redesigned beyond recognition, served in dozens of arduous little courses over many hours and costing hundreds of dollars. The fans and practitioners of this cuisine love to talk about the chemical properties of the ingredients and the complex physiology of taste; but what they’re really doing is creating the first common ground between science and faith. Nobody goes to one of these restaurants to eat dinner with friends. Nobody just drops in. You can’t, for these places are difficult to reach—so remote from our everyday culinary expectations that you have to reserve months, maybe a year, ahead of time. These aren’t places for skeptics and infidels. When at last you sit at a table waiting to consume a feather made of apricot pulp, radish skins, and cotton candy, suspended over your mouth by an attentive waiter, you do so in the sure and certain belief that you’re about to be transported to realms undreamed of in the world of mere food.

I don’t want to give the impression that these chefs are too lofty to distribute recipes, however. Far from it! Their books are packed with recipes, each written up in solemn and precise detail. Here are such classics of the ritual as beet spheres and gin-compressed rhubarb (Alinea), spherical-I green olives served on a medicine spoon (El Bulli), and a flaming sorbet (Fat Duck), all perfectly achievable in a home kitchen. Or so the masters claim. Ye of little faith, go eat Ring Dings.

Pinterest

Pinterest