IAN'S TAKE

A sense of humor is an admirable quality, a sense of whimsy,

too. Stanton Social, a high-end restaurant on Manhattan's Lower East Side, appears

to have both. The menu reads like a sophisticated joke book: "Old-School

Meatballs - $11"; "Potato and Goat Cheese Pierogies - $8";

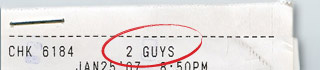

"Kobe Beef Sliders - $6." Last night, Alan and I strolled into an

empty Stanton Social. The

hostess painfully explained that they were fully booked, but we could eat

at the bar. Already, we knew, this high-low joke was on us. I paid $10 for what

turned out to be one-fifth of a bottle of Guinness, served in a flute. We

ordered four sliders and a side of fries. The sliders were good, but they were

sliders, I didn't want more than two. The fries were good, but they were fries.

With tip: $62. As we left, the dining room was still empty. Our research was

far from over. We headed to one of Manhattan's most raucous dive bars, The

Patriot Saloon—where sliders cost $1 apiece. We vowed to spend $62 with tip,

but once again, the joke was on us. Twenty-six dollars into our endeavor, we

reached our bursting points, after a dozen grilled, greasy, and perfectly

cooked mini-burgers (Stanton's were overdone), and there was plenty of food

left over, along with half a pitcher of beer. Eating high-low cuisine is like

having an affair to save your marriage: Sometimes it can actually work. But

it's risky, needs to be executed well, and in the end has to be worth the price

you're willing to pay . . . usually, it's not.

ALAN'S TAKE

A little Kobe beef here, a dash of smoked fleur de sel

there, top if off with some truffles, and the classics will be as good as new,

right? I'm supposed to write here in defense of the chefs who think like this.

But I can't. Humble foods are getting played with at restaurants around the

country. Burgers, fries, hot dogs, chicken wings, and even jalapeno poppers are

classics for a reason. It may seem silly to say this about hamburgers, but the

appeal is primal—it's about comfort and deep satisfaction. The sliders at Stanton Social are

indeed satisfying. They're good, even. But are they better than the sliders at

The Patriot? No. Try as I might to think of the advantages that the Kobe sliders might have over the plain old sliders, I can't. Too often the high-low dish

is simply the end result of a chef throwing a few expensive ingredients into

the mix, dressing up the presentation, and jacking up the price. Stanton

Social's sliders are no exception. Instead of ketchup, they use some kind of

sauce. But that sauce? I'd be shocked it if weren't ketchup-based, because it

adds the same amount of sweetness, tang, and moisture that Heinz would. The

miniature brioche buns that Stanton Social serves their sliders on are

perfectly fluffy, perfectly soft, and are perfect replicas of the bought-in-bulk

Martin's Famous dinner rolls that Patriot uses for theirs. Sure, the dinner

rolls are made with cheaper ingredients and might be a day or two old, but when

you're talking about cheap burgers, who cares? The beef that Stanton Social

calls Kobe, but is in reality American Kobe-style, is moister and

beefier-tasting than the no-doubt-it-was-frozen-this-morning beef at Patriot,

but with condiments piled high, it's a wash. As for the herb-dusting that the frites

(they'd never be so gauche as to call them fries) at Stanton receive? They're

no crispier and no more flavorful than Patriot's frozen fries. They might even

be the same frozen fries that Patriot uses. After all, even the world's best chef approves of Sysco fries. So what's the point?

The point is that great restaurants are great restaurants, but the money needed

to get the best ingredients and to hire a staff that can consistently make the

highest quality food is lost when you use it to make sliders or French fries

with red chile mayo. When I drop $60, I want to be impressed. Burgers are as

good as they're going to get—and they are really good—and no matter

how much micro arugula and heirloom ketchup you use, you're not going to make

them any better.

Pinterest

Pinterest