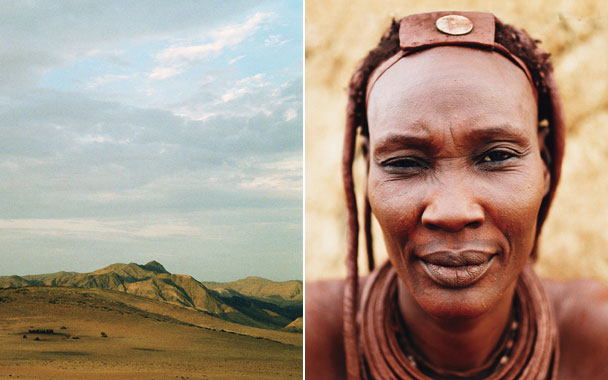

The balloon was not supposed to fly over the dunes. It was supposed to rise with the sun, drift over the pale green savanna and the bone-dry bed of the Tsauchab River, and ease to the edge of the red Dune Sea in southern Namibia, the centerpiece of what’s known as the Oldest Desert in the World. The undulating sand mountains around Sossusvlei—at sunrise, they’re colored the vermilion of a dragon on a Japanese kimono—are the arresting face of one of the most barren, most peaceful, and least-known countries in southern Africa, one that’s nevertheless becoming the next frontier of luxury travel.

I had arisen long before dawn at nearby Little Kulala, one of three upscale camps run by Wilderness Safaris, a conservation collective begun two decades ago to promote ecotourism across southern Africa. Little Kulala, situated on a private reserve, has 11 thatched villas—complete with air-conditioning, plunge pools, and open-air mattresses for stargazing—decorated in muted grays and beiges that are more Calvin Klein than Ernest Hemingway.

The lodge is adjacent to Namib-Naukluft National Park, which hugs the Atlantic coast. The park, the largest in Africa, is almost twice the size of Massachusetts. But it’s not the only mega-desert in Namibia; the Kalahari runs along the country’s eastern border, abutting Botswana. In effect, Namibia (the name means “vast open space” in the language of the Nama people) has a desert to the east, a desert to the west, and very little in between. Although it’s twice the size of California, it has a population about the same as that of Houston—just 2 million people concentrated in the north, where rain is more plentiful. On a U.N. list of population densities, Namibia ranks 225 out of 230, barely ahead of Mongolia. Neighboring Angola, by contrast, has 5 times as many people per square mile; South Africa, 15 times; and Rwanda, 137 times.

For all practical purposes, Namibia is empty.

The main reason for this vacuum is the harshness of the terrain. When the European powers were eagerly divvying up Africa in the 19th century, even they were put off by the rugged conditions. Beginning in 1884, the Germans did eventually annex the territory as South-West Africa, but South Africa, a British ally, took it over during World War I. South Africa eventually lost the territory as the result of an uprising led by the Marxist South-West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), formed in 1960. Namibia became independent in 1990.

Still, the new country has few resources. (It reminds me of that old joke about Moses wandering 40 years in the desert before picking the one place, Israel, that had no oil. Moses would have loved Namibia.) Half the inhabitants depend on agriculture, mostly subsistence farming, for their livelihood. There are some minerals, but the uranium and diamond mines have been well picked over. Even the mackerel and hake fisheries, once the backbone of the economy, have suffered from overfishing, currency fluctuations, and rising fuel costs. Flying north one day above the Skeleton Coast, a fearsome stretch of the Atlantic where countless ships have run aground in the wind and fog, I asked the pilot of our four-seat Cessna about all the vessels anchored in the harbor. I had heard that ships had been prospecting for new diamond supplies offshore.

“They are fishing boats from Spain and Lebanon,” he said.

“And what are they fishing for?”

“Sardines.”

Ah. Profitable, perhaps, but hardly a growth industry. Namibia is depleted.

But therein lies its allure. Most first-time tourists to sub-Saharan Africa come for the game. They stay in one of the pricey hideaways that have proliferated in Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Botswana, and they go on game drives at dawn and dusk to spot the vaunted “big five”—lion, leopard, elephant, Cape buffalo, and rhino—and enjoy luxurious beds, spa treatments, and a bottle of French Bordeaux with their Cuban cigars. While these dream getaways provide a fantasy introduction to Africa, they are, well, passive. What sets Namibian travel apart—and what makes the country an ideal destination for a second trip to the continent—is that it is active. Game is not the focus of a trip here; the enormous sweep of countryside is. And in most places you can get out of your Land Rover and walk right into it.

The best place to do that is Sossusvlei, where the dunes, which form a natural corridor along the riverbed, summon the adventurer to climb them and experience, firsthand, the strange ecology of living sand. Like many things in Namibia, the sand on these dunes comes from someplace else. The red-tinted grains—which, depending on the time of day, change in color from apricot to sweet potato to cardinal—come from the eroded sediments in the Orange River (which forms the border with South Africa), flow northward from the cold South Atlantic in the Benguela Current, then gust eastward onto the Dune Sea. The farther inland the dunes are, the redder they become, because the freshly blown grains mix with older sand, in which the high iron content has had more time to oxidize.

Climbing in the dunes (some of them 1,000 feet high), as visitors can do at famed Dune 45 or the gigantic Big Mama and Big Daddy, you realize that they aren’t static but constantly shifting. Much of each dune is held in place by vegetation and inner moisture. But the tops move like slithering snakes, as year-round winds blow sand onto the slip face and send it avalanching down the leeward side. The peaks can migrate as much as 25 feet in a year. Put footprints along one face while climbing up, and by the time you climb down an hour later, they will be gone. In Sossusvlei, the dunes are alive.

Pinterest

Pinterest