Full o’ th’ milk of human kindness” is how Shakespeare describes one of his leading men, but it is a better description of Lou DiPalo. Lou is the proprietor and genius loci of DiPalo’s Fine Foods, a 97-year-old latteria, or milk store, that has grown into a cheese and Italian specialty foods shop (the world’s greatest in my opinion) on the corner of Mott and Grand streets, in what used to be Manhattan’s Little Italy (but is now Chinatown). Lou’s face is equal parts kindness, tiredness, and boyish animation. Milk is his lifeblood. On occasion, when he looks pale and weary, after a night driving a delivery truck and a long day spent behind the counter, I imagine that milk is actually running in his veins. It is whole milk from happy cows, unhomogenized, warm, full of caseins (proteins essential to the production of cheese)—and it is what keeps him going, seven days a week, working the kinds of hours that would wear out somebody with mere hemoglobin to rely on. “We sell three hundred Italian cheeses,” Lou told me recently. “We counted them one day, my brother and me, and when we were done we said, ‘We are out of our minds.’ ”

Twelve years ago, I moved into an apartment four blocks from DiPalo’s and became a regular customer. Later, Lou and I became friends. I discovered that Lou likes to talk. He is fond of the soliloquy. He will explain what different cows were eating and metabolizing when they were milked—either spring flowers or intense first-growth summer grass or delicate autumnal second-growth grass or winter hay—and how cheese can contain whole landscapes and traditions in its flavor, color, and texture. “I talk too much,” he admitted recently, and I planned to protest, but he decided to elaborate. “I want you to taste everything. Before I sell it to you I have to share it with you. The shop’s an extension of my home. The counter is my dining room table.”

DiPalo’s is a warm, raucous, multigenerational family dining table. Lou’s late father, Sam, designed the store logo, which Lou describes as “a happy cow, giving a little wink. The mouth is a little squashed, but that’s because it’s supposed to be up against the window to give you a kiss.” It is a fantastical sort of place. And Lou DiPalo is, in a way, a fictional character—his real name is Luigi Santomauro, as was his grandfather’s. When the original Luigi, with his wife, Concetta, first opened the latteria, there was already a Santomauro’s on the block, so they put Concetta’s maiden name on the sign instead. DiPalo stuck, and Lou, like his father before him, still uses it professionally. Compromise became a culinary institution.

Last summer, I asked Lou if he thought there was any part of Italy in need of discovery.

Without hesitation he replied, “Trentino-Alto Adige, in the very north. It’s the bridge between the Mediterranean and Germanic and Austrian northern Europe. The people act like they’re not Italians, but they love being Italian.” Coincidentally, my favorite cheese is Crucolo, a semisoft cow’s-milk product, riddled with holes (Lou calls this “eye formation”), that is made by a family in Trentino’s Valsugana Valley.

“Do you mountain climb?” Lou asked. “Do you want to spend the night on a glacier? I can put together some wine and cheese and speck people, suggest some unvisited places, maybe find you a mountain guide.”

He was serious, I knew, but then he completely surprised me: “If you want, I could come with you.”

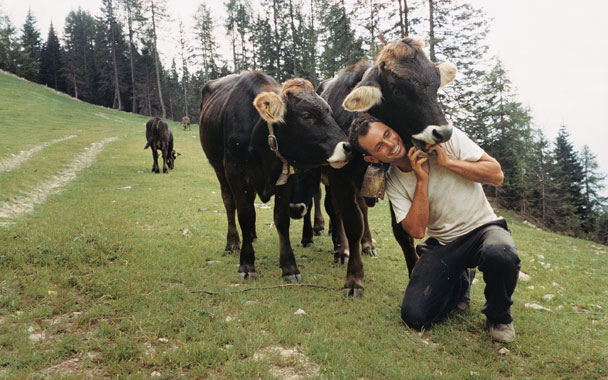

Since Lou’s is a magical reality, everything fell into place. My wife, Daphne Beal, and our son, Owen, came along, and in the middle of July we met Lou in Merano, a small town in the northern part of the region. Thirty minutes later we were on a gondola heading up a mountain. It dropped us off in a pasture, where we followed hand-lettered signs pointing toward lunch. A path took us through high meadows where the bells of brown and gray cows rang like wind chimes. There were no fences. Walking right up close to these cows, Lou explained their bells in much the same way he explains cheese in his store: “These are bruno alpina and grigio alpina cows, and their bells differ in size according to their value and importance. The head cow, the one that leads all the others up the mountain in the spring and back down in the autumn, will have the largest and most elaborate bell and collar.” From then on, every time we spotted cows—and they were everywhere—Lou slowed down, hopefully, trying to spot the leader’s bell.

“Alto Adige,” like “Lou DiPalo,” is an alias—after World War I, just before Concetta and Luigi Santomauro were getting their latteria going on Mott Street, South Tyrol, then part of Austria, was ceded to Italy and renamed Alto Adige. Most locals speak German and call the region what it has always been called, Südtirol. All the towns in the area have Italian and German names on their signs. Depending on how close you are to the border, the German name will come first.

After seeing cows and admiring their bells, we were hungry for cheese, so we visited a man who describes himself as a “cheese caretaker.” Hansi Baumgartner ages and refines cheeses in a Mussolini-era decommissioned bunker deep in the woods near the Brenner Pass, and sells them in a beautiful store and tasting room in Varna (a.k.a. Vahrn). All the milk in Hansi’s cow’s-milk cheeses is raw and comes from the Pinzgau breed, which is brown with a white stripe down the back and produces a small amount of milk with a high percentage of caseins. This is a cheese cow par excellence.

We tried a Pinzgau cheese, covered in high-mountain hay, that had been aged in barrels full of more hay. It tasted like summer. We sampled one called “the brick,” which was covered in smoked tea, tea having tannins that help conserve and mature—and, in this case, bring out a surprising sharpness in a young cheese. We learned about wine-soaked, or “drunken,” cheeses—a common trick for masking the taste of an inferior product, though Hansi makes a deliciously subtle one with the local grape, Lagrein. We tried more than a dozen different cheeses. My favorite was a sweet Gorgonzola mixed with fresh cream—cheese crossed with gelato. The more we tried, the more eager we were to try more—and the more Hansi gave us to try, moving back and forth from his cheese case and cheese board, opening bottles of Pinot Bianco, until he eventually sat down and joined us, bringing along some dessert wine. Our lunch consisted entirely of cheese.

Following tradition is the best way to make good food. Despite his improvisations, Hansi makes cheese the way cheese used to be made, and the small scale of his operation allows him to be an exception to current trends toward the mechanical and the oversanitized. (Brined cheeses that are now power-washed and blow-dried were once rubbed with oil and dried in the sun; others used to age on wooden shelves—most still do—but the EU currently wants all such surfaces to be made of aluminum or plastic.)

Speck, which is still produced on a relatively small scale because it’s consumed almost entirely in Trentino-Alto Adige, is an example of something that, though industrialized, is made in much the same way it has always been made. Alto Adige’s cuisine is simple Italian combined with surprising elements of the elevated and technical cuisine of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. So you might think of speck, the echt expression of the region, as prosciutto with an imperial influence. Whereas prosciutto is salted and cured in a uniform fashion, speck is rubbed with herbs, spices, and berries and, depending on the Alpine microclimate, smoked for different lengths of time and with different hardwoods. While prosciutto is well defined and consistent, speck is variable and you could even say eccentric.

Before meeting Franz Recla, who produces the magnificent speck (low salt content, very light smoke) sold at DiPalo’s, Lou wanted to try what he described as “farmhouse speck,” made by a family for their own consumption. To this end, we drove a series of tight mountain switchbacks, pulled onto a nearly invisible dirt road, took it through some fields, skirted the edge of a cliff, traversed another field, and arrived at a whitewashed stone farmhouse. The house has a name—Johannser Hof—and during the fall, after the harvest, visitors can arrange to come and have a meal here. For the rest of the year, the Brunner family raises livestock and makes speck. Georg Brunner, a lean, white-haired man in his sixties, showed us a chamber where speck has been smoked for the past 800 years—the ceiling and walls were lacquered black from centuries of single-minded purpose. Then we visited the cool cellar where postsmoke aging occurs. Farmer Brunner cut down a piece and carried it up to the family dining room, where Michaela, his daughter-in-law, in dirndl, brought us a ceramic pitcher of homemade red wine.

Lou sliced. Grandchildren appeared and took bites straight from his fork. We felt very much at home. Then Brunner took us outside to meet “next year’s speck.” In the farmyard his son came and said hello. As we admired two pigs, we heard frantic noises from the adjacent cattle barn. A cow was calving! I turned to Michaela, who had changed out of her dirndl and into blue coveralls, and said, city boy excitement in my voice, “Is it having a baby?”

“No,” she said. “It’s having a veal.”

Shortly thereafter a brown and white calf, one of Hansi’s Pinzgaus, I imagined, was born right at our feet, yanked into the world by two generations of Brunners (father, son, daughter-in-law) pulling on a rope.

Lou says he goes to Italy for two reasons, personal (“Coming here is not only about getting new items, new food, but about people, bonding. It makes me a better person”) and commercial (“Italian business isn’t done in an office, it’s done at a table”). After my visit to the Recla speck factory it occurred to me that, because of the personal relationships Lou has with his suppliers, by shopping at DiPalo’s you can take home food that has arrived there at the end of an unbroken chain of respect, care, knowledge, friendship.

The first thing you see on entering the tasting room at the Recla factory is a photo of Lou, prominently displayed, an arm around the company’s export manager, at DiPalo’s, the two men proudly brandishing the first speck to be sold in the United States after an absence of many years.

Franz Recla, the company’s owner, walked into the room, embraced Lou, and said, “Oh my dear Lou! How is your mother?” As at the farmhouse, family is at the center of the business. Franz is a third-generation speck maker, and when we toured the plant we met the fourth, his 12-year-old son, checking out the packaging line. We were walked through every stage of the process. Amaz-ingly, Recla’s is a meat-processing plant that actually makes you hungry.

At the end, as we watched finished packages of speck being inspected by his son, Franz Recla pointed to Lou and said: “I once visited a cheese and cured-meats store in Milan, early in the morning, and saw an old counterman who did things very much in the correct way. He was slicing prosciutto, and when I asked him why he did it the way he was doing it he explained that the lower leg was for the students, the upper leg for the working people, and the best part, the culatello, was for the refined ladies of Milan. He took me through the whole process of how to slice each part.

“Then, when I first came to New York with speck, for the Fancy Food Show, people asked me, ‘Can you eat this?’

“I thought, ‘Oh, no, I’ve got a long way to go in the U.S.’ Until I went to DiPalo’s. I saw my speck there, being handled and cut correctly (against the muscle’s grain) by this man—just like in Milan—and I was so happy.”

In Trentino, where the signs are no longer in German, we were offered Prosecco, meat, cheese, and a tour of a slaughterhouse in the village of Scurelle. The slaughterhouse was in a gorgeous spot, “tucked in by mountains,” as Lou observed. Our expert guide was Danilo Purin, who told us the place used to be a sock factory. Danilo’s father, Giordano, invented Crucolo, which has a gentle, Asiago-like sharpness. Danilo is keen to expand the family’s food business, and a modern yet traditional facility, not unlike the Recla plant, is his idea of how to do it. The slaughterhouse will not only process meat from local farmers, who have a cooperative stake in the operation, but will allow visitors to actually see the butchering take place, and instruct students in curing meat. Danilo, gesturing toward Mecca, informed us that it would also do halal slaughtering for Muslims. Lou turned to me and said, “He’s got a vision, this man.”

That evening, in the family’s restaurant, we toured the dirt-floored basement, where Crucolo and meat were aged, and where a single long sausage circled the ceiling like a carnal chandelier. An entire side of pork—head, belly, legs, trotters—was being made into “the world’s biggest speck,” and a Crucolo cheese the size of a child’s wading pool was aging in its own alcove. Then we met and talked with Giordano Purin.

Giordano, like Hansi Baumgartner, had started out as a restaurateur and discovered a cheesemaking streak. “Another guy was making a cheese around here,” he told me, “but it was only a cheese in name, not taste. So in ’67 I started working on my own cheese for the restaurant. All our customers were local at the time. And until recently this was an area of Italy where the only tourists were migrant laborers, so we were making something to suit our own tastes. I spent five to ten years playing with the ratio between fat and protein.”

When I told Lou about our conversation, and the cheese only in name, he deadpanned: “We have that cheese too.”

Cheese breathes. It’s like a sponge, and it takes on the flavor of whatever is around it. Likewise cured meat. In every aging room we visited, from Recla to the Brunner farmhouse to Hansi’s Mussolini bunker to the Purins’ basement, Lou pointed out the screened vents (or gun sights) that allowed fresh mountain air to circulate inside. “If you make a cheese by a highway,” Lou told me, “it’s going to taste like a highway.”

Our last stop on the trip was Pinzolo, at the center of an unspoiled valley where whole vistas were organic, and where they make Grana Trentino “Biologico,” an organic mountain cousin of Parmigiano-Reggiano that Lou is about to start selling in the shop.

At a hilltop milking station and pasture, called a malga, we met Fabio Maffei, a wiry, sunburned young man in sweats and a soccer jersey who is in charge of the local organic herd. He introduced us to his herd’s bull, deftly bringing the animal close using the ring through its nose, and invited us to lunch at the summit lodge of a nearby ski resort with views of the slopes where Pope John Paul II used to ski. To get there, we took a chairlift straight up, while Fabio, improbably, took a motocross bike.

It was a setting that, transposed to America, would have guaranteed microwaved nachos and frozen burgers, but, this being Italy, the summer chef was a teacher from a culinary institute in Trento, the district capital, and his specialty was mushroom risotto—the best I’ve ever had. We all ordered it. Fabio told me that his cows were never tied up, not even in the stalls during milking. The rennet he uses comes from cows that have been treated the same way. He took these strictures very seriously, while noting that “Italians would rather spend money on a lot of things before spending it on organic cows.” He himself, for example, though sunburned in sweat pants, drove a Ferrari.

Lou gave Fabio a DiPalo’s baseball cap with a happy cow on it. Then we said good-bye and took the chairlift down the mountain.

At the bottom we were surprised to see Fabio reappear on his motorcycle with something large draped over his shoulder. It was a cowbell on a beautifully tooled leather collar. He took it off his shoulder and gave it to Lou.

A rare moment of silence, till Lou said, “I’m going to put this in my window. This is the lead cowbell.”