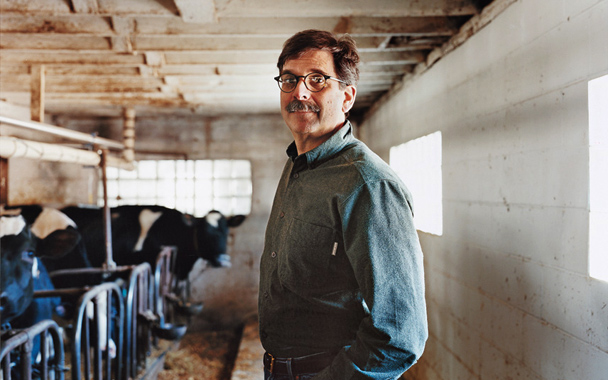

Writer David Tamarkin introduces readers to Mark Kastel in our November 2008 issue (“Organic . . . Or Else”). As co-founder of The Cornucopia Institute, Kastel and his team have spent years exposing the unsavory business practices of big corporations that claim to operate organically. Cornucopia’s dairy scorecard, an update of which was recently released, ranks every organic milk producer in the country according to how strictly they adhere to the organic movement’s principles, and the results for most corporate milk producers are far from flattering. Tamarkin spoke by phone with Kastel as he was making one of his regular road trips through the Midwest, so he had lots of time to expound on the spiritual side of organics, why he loves Publix, and why he can’t wait for a change—any change—in the Oval Office.

David Tamarkin: There are a multitude of issues facing the consumer at the supermarket. They have to think about whether products are Fair Trade, locally grown—all sorts of things—and organic is just one of them. So I’m wondering: Do you believe that sussing out which foods are honestly organic is the most pressing issue that consumers are facing?

Mark Kastel: One of my own little things is: “All I want is…everything.” As a consumer, obviously I want—and I think my sentiments are fairly representative of committed organic consumers—I want safe food. I want nutritionally superior food, and we know food that’s grown truly organically is truly superior—there’s a growing body of scientific literature that indicates that. I want food that’s really local, not just another kind of marketing hyperbole. So I want all those things. I want the environmental impact and the decisions of my purchasing to have a positive influence on how we steward the earth, and I want the animals and people involved to be fairly and humanely treated. So that’s everything. I want it all.

Organics continues to grow really aggressively; up to now, the day we’re having this interview, the indication from talking to people in the industry is it’s holding up phenomenally well, even in this terrible economic climate we’re in. But we’ve seen growth eclipsing even the organic growth in areas like the farmers markets around the country. There are now about 4,700 farmers markets in the United States, according to the USDA. That’s doubled in the last few years. The other mechanisms for local and direct marketing—CSAs, farm stands, web-based marketing and local home delivery—these vehicles have experienced exponential growth eclipsing even the historic 20 percent per annum that organics enjoy. So these consumers, many of them are voting to vet their organic product in a very intimate way. They’re forming relationships with local or regional farmers or business enterprises, so that they can understand who’s growing their food, how it’s being grown. And there’s a sense of place being built in, where their food is from. But many people around the country still need to depend on their supermarket chains or Whole Foods. And then the integrity of the organic label is of a paramount importance.

DT: For someone who’s a watchdog, you sound fairly optimistic right now.

MK: I’ve never lost my optimism about this industry. Yes, there are very poignant threats from powerful economic entities, but what makes me optimistic is that unlike all the other political fights I’ve been involved with in agriculture over the last 25 years, our secret weapon (and what we’re really engaged in here at Cornucopia) is that we have this coalition between the farmers and millions of consumers who just passionately care about these things.

To take all family farmers, all farmers in the United States—people who are by their livelihoods engaged in production agriculture—it’s about 1 percent of our population. Back in the earlier part of the last century, that was 30, 40 percent, and in some states demonstrably higher numbers. Then, when they talked about the farm vote, people had clout. Today farmers really don’t have marketplace and economic clout. And organics was founded as an alternative economic system, so that social justice would be built in. The reason that Cornucopia has any voice out there and has made a difference is that we’ve been successful in building these bridges between our farmer membership and consumers who get it. Consumers who really care. [And] it’s a two-way street, this love affair between the farmers who are engaged in these value-added enterprises and the consumers who are willing to compensate them fairly and go out of their way, whether it’s to pick up their CSA box or go to the farmers market or maybe drive all the way across town to a natural foods co-op. These consumers are willing to go out of their way to make that connection, and it’s rewarding on both sides.

DT: They really do have to go out of their way—it seems to me that as time goes by consumers have to go even more out of their way because they have to do more research to find out if their food is really what they think it is.

MK: Right. We’ve had as many as 9,000 hits on our organic dairy scorecard in a day (that’s usually after some sort of publicity comes out). These are people doing their homework. One of the things I say frequently in my speeches is that for many people, doing this research adds meaning to their food, that there’s actually a spiritual connection. And it’s not a coincidence that in most religious vernaculars, prayers at mealtime are an integral part of the religious practice. That in saying thanks for the creation and the creator, we understand that the food didn’t just come—and I’m speaking historically—that the food didn’t just come in this foam tray with shrink wrap on top. It came from the earth. It came from an animal that was part of creation. And it wasn’t that many generations ago for our species that when it didn’t rain at the right time, in the right season, your kids literally, literally starved to death. So when we thanked God for that meal, we meant it. And so for many families, joining a CSA or buying directly from a farmstand or buying off the Internet that quarter of beef, or that hog to put in the freezer, this is a way that food really is connected to the earth, and that these stewards and shepherds are the ones that bring us our meals.

Pinterest

Pinterest