José Bada is convinced he has the best job in the world. Admittedly, the cell phone reception at his office isn’t so great, and his competitors can be wolves. But the 50-year-old makes a decent living, his work environment can’t be beat, and he is confident of his product’s quality. “I get to work in the Picos de Europa,” Bada says, referring to the mountain range stretching through north-central Spain that constitutes his office wall. “And the cheese we make is very special.”

That’s an understatement. Cabrales is one of those intensely indigenous cheeses, tightly linked to the tiny region of northwestern Spain where it is made. In fact, only four towns can claim the Cabrales name for their cheese. The region, in the Asturias province, is startlingly beautiful. Bright green grass surrounds the base of soaring granite peaks that even in summer can be topped with snow and are broken only by the occasional alpine lake. Small herds of cows, sheep, and goats graze in the area, the syncopated music of their bells puncturing the brisk air.

That’s the other special thing about Cabrales: It’s typically made from a mix of milk of three animals—sheep, goat, and cow. Bada keeps all three species, and his herd currently measures 60 sheep, 55 goats, and a handful of cows. Every day, as long as the snow isn’t too deep, he and his dogs lead the herd up from his home in the village of Tielve to the steep highlands of the Picos. He’s been doing the same thing for as long as he can remember. “My parents, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, they were all shepherds,” Bada explains. “This is what I was born to do. It’s all I’ve ever known.”

Bada inherited his cheese recipe from those ancestors, and he hasn’t changed it. It starts by mixing the morning milk with the evening milk. The quantities of each animal’s milk vary with the seasons—sometimes it’s more sheep, or more goat—as does the amount of rennet, and the amount of time spent gently heating the mixture. “Every cheesemaker has his or her own process,” Bada notes, “but in general you heat it for about 90 minutes.” The whey is then separated from the paste, and the cheese is set into molds, salted, and left to dry for anywhere between 15 and 30 days.

And that’s where things get really interesting. Because Cabrales cheese—real Cabrales—can’t be cured in what Bada calls an “artificial” room. It has to be left to ferment in one of the dark, dank caves that populate the Picos. When the cheeses are ready, Bada will hike his up to the mountain—either on foot, if there are only a few of the rounds to transport, or by horse if he’s got 20 or 30—and place them in “his” caves for anywhere between one and three months. Like any proud artisan, he won’t tell you where his caves are located, only that they have to be “natural,” not manmade rooms. “Cabrales gets its flavor from nature,” Bada says. “You can’t fake that.”

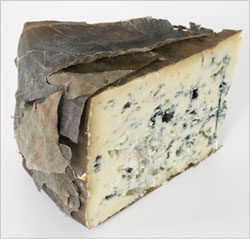

That flavor is distinct. Cabrales is the bluest of blue cheeses—so blue, in fact, that it often appears almost uniformly gray. Made from raw milk, Cabrales tastes intensely funky and rich, with a bit of spiciness on the finish, and so much mold that those with penicillin allergies—including this writer—have been known to suffer for it. The texture, Bada counsels, should be creamy. “I always say that the way you know a good Cabrales is that, 30 seconds after eating it, you want another bite.”

For centuries, Cabrales was the most idiosyncratic of foods, a cheese that farmers with any kind of livestock would make from whatever milk was on hand. The weather also plays a role. “You have to respect the season, and work with nature,” says Bada. “If it’s sunny out, you do one thing; it it’s rainy, you do another. But it all depends on nature. She’s the one who commands.”

Pinterest

Pinterest