A few months ago, leafing through a kitchen-design magazine in the checkout line of the hardware store, I realized the kitchens in those pages were not created for people like me. It’s not just the income disparity. The people who use these high-design kitchens don’t cook like I do. The storage spaces are all wrong. The cleanup system is insufficient. The butcher-block countertops are not meant to have anything chopped on them, let alone butchered on them.

On our farm in northern New York, we produce a full diet, year-round, for 200 people, and grow about 90 percent of the food we eat in our own home. I’m at the extreme end of the whole-foods scale, but there are plenty of cooks on this continuum, from CSA members to farmers’ market shoppers to those simply striving to use more fresh, local food. I began dreaming of designing a kitchen for people like us, a space where cooking whole foods would be comfortable and convenient. It would also need to be durable, thrifty, and resource-efficient.

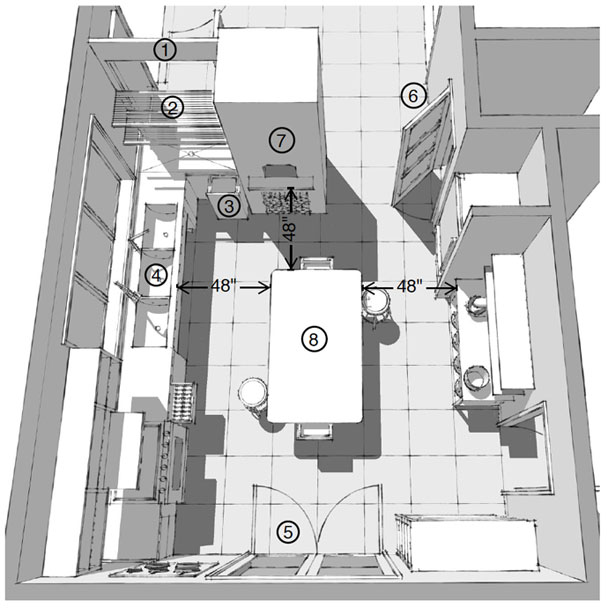

To help design the 21st-century whole-foods kitchen, I consulted my neighbors, Mark and Erin Hall: The Halls met at the Rhode Island School of Design and run a local studio together, Hall Design Group, specializing in practical, sustainable interior and building design. They also like to cook, and they belong to a CSA, so much of their food comes into their house fresh and dirty. When I told them about my kitchen-design challenges, they both got it. We agreed to meet in my kitchen, to look at the systems I currently use and address the problems I encounter. To keep ourselves grounded in reality, we imagined this new kitchen as a remake of my existing kitchen, with a total footprint of 270 square feet, about the same amount of space I have now. We did not set a specific budget for this project, but aimed for changes that a motivated farmer could actually afford to make.

The first step required an act of bravery on my part: It is embarrassing to bring people with a highly developed sense of aesthetics into my kitchen. Our farmhouse was built in 1902 and last renovated, from the look of it, around 1976. We have lived here for nine years and made no aesthetic improvements. Until our second child was born and life got too crazy, we cooked two meals a day in here for up to 15 hungry farmers, so the decor has evolved into a strange mélange of commercial efficiency and faux-brick funk. Imagine The Brady Bunch meets Top Chef with a dash of Green Acres thrown in, then add a few decades of wear. Parts of it work extremely well, but the form ain’t pretty. The Halls, to my relief, were professionally unshocked and got right down to business. Over a series of design meetings, we came up with the following plan.

Prep Space

I picture hell as spending eternity dicing root vegetables on a tiny plastic cutting board. The whole foods I cook with are bulky and require lots of prep space for everyday work, like paring potatoes, chopping kale, or cutting a chicken into pieces. And when it comes to big seasonal jobs—always more fun with multiple people—there’s no such thing as too much space for tasks like canning tomatoes or slicing rafts of strawberries for the freezer.

The Halls decided to make a proper butcher-block table the centerpiece of the new kitchen; before long they had added so many improvements that they dubbed it the Swiss Army table.

In my current kitchen, prep work is done at a large, much-loved, old dining table planted in the middle of the room. Years ago, we put the table up on blocks to make it the right height for chopping, and we use the whole table as a cutting board. (I scrape it off and scrub it down after use with salt and vinegar.) The Halls decided to make a proper butcher-block table the centerpiece of the new kitchen; before long they had added so many improvements that they dubbed it the Swiss Army table. First, the height is adjustable: I am 5’2’’ and my husband is 6’6’’, so a telescoping table is a necessity if we both want to work ergonomically. But an adjustable work surface is also handy for making low-down jobs like kneading dough more comfortable. I hate jogging around the kitchen for tools, so the Swiss Army table includes a place to keep knives and a few everyday utensils, with open shelving below for serving dishes. My favorite detail is a pair of deep, pull-out drawers at either end of the table: These hold removable stainless steel compost containers, so scraps can be scraped off the work surface and disposed of directly. This also neatly solves the problem of keeping the unsightly containers both handy and out of sight.

Food Storage

Shelter magazines tend to show boxcar-size refrigerators with cavernous freezers. This is a great way to supersize your food’s carbon footprint—more than 30 percent of food energy is burned after you bring it into your home, according to the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems—and if you’re cooking seasonal fresh food each day, all those cubic feet are totally unnecessary. A week’s worth of fresh food fits into a pretty small fridge. For larger or longer storage, a root cellar and a chest freezer in the basement offer more for less energy. The Halls sketched a small, efficient refrigerator and freezer into the kitchen and improved the utility of my root cellar by adding a sink at the bottom of the basement stairs, for rinsing farm-dirty vegetables before bringing them up to the kitchen. They also specified a one-way swinging door at the top of the stairs, to avoid fiddling with a doorknob while carrying an armload of rutabaga.

Cleanup Systems

I suspect that for many, one of the biggest barriers to cooking whole foods—rather than packaged or convenience foods—is a reluctance to make a mess. Who wants to face a giant stack of dishes and gear next to a little tiny sink at the end of the day? My answer is to supersize your sink: My current kitchen is home to a large stainless steel three-bay sink. We bought it at a dairy auction for $10 and built a tiled countertop around it. The original purchase was simply an act of frugality, but the system works so well I would not part with it, even in exchange for an automatic dishwasher. The first bay is where dishes are sprayed off, the second is for washing, and the third is for rinsing. Two sinks of hot water will wash a dinner party’s worth of dishes plus all the pots, pans, and irregular items that would never fit in a dishwasher anyway.

My new dream kitchen reuses this sink, but the Halls improved the whole system by installing drying shelves near the rinsing bay. Because these drip-drying shelves are set within a pass-through window to the dining room, clean dishes are within easy reach when it’s time to set the table. The Halls even call for an ingenious swing-out compost bin beneath the pass-through counter, where dirty plates can be scraped when they come back through the pass-through.

Creature Comforts

Maybe the most basic requirement of the whole food kitchen—OK, of any kitchen—is to make it an inviting space that you want to spend time in. To that end, the Halls added clerestory windows high up on the wall to bring natural light deep into the space, plus a set of French doors that lead to the kitchen garden, where I grow herbs and cherry tomatoes. Underfoot, we imagined acid-stained, scored concrete floors with radiant heat. They would look beautiful and also keep us comfortably warm in the winter, typically long in these parts. Erin, who specializes in interiors, noted that we’d want to offset the more commercial elements of this kitchen with warm, natural colors on the painted surfaces. She likes milk paints, which are durable and nontoxic, with no volatile organic compounds. You can buy milk paint commercially, but since we have our own dairy cows, I’d be tempted to make it myself. Finally, we added one aesthetic element that has long been on my wish list (even though it would bust this farmer’s budget): a wood-fired bake oven, large enough for loaves, multiple pizzas, or a slow-roasting leg of lamb. For now the bake oven, like the rest of the improvements, is part of a long-term renovation plan worth saving up for, but if and when this kitchen comes to life in my home, the Halls will be the first people I invite for dinner.

Kristin Kimball is the author of The Dirty Life: On Farming, Food, and Love and a frequent contributor to Gourmet Live. Her most recent article was Winter Feasting at Essex Farm.