A decade ago I had my wisdom teeth extracted, and during the several days of convalescence that followed, I watched most of Robert Bresson’s films. I’m not sure which of the two was more painful.

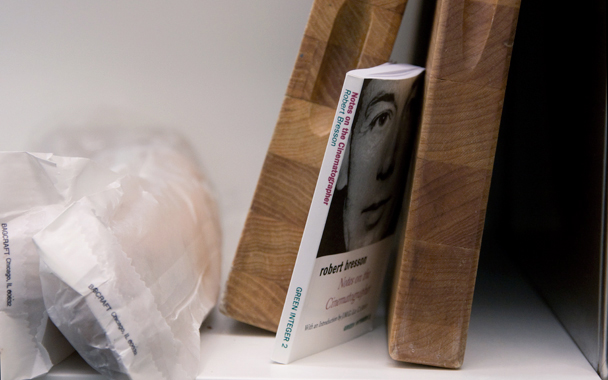

Probably the least watched of the French auteurs, Bresson made uncompromising, severe films—including Pickpocket, Diary of a Country Priest, and Au Hasard Balthazar—that somehow manage the trick of remaining irresistibly alive. Moved by my mini-marathon, if in no hurry to watch the films again any time soon, I tracked down a copy of Notes on the Cinematographer, a collection of Bresson’s observations about filmmaking written between the years of 1950 and 1974.

I liked to carry the small book around in my back pocket, and gradually I found that I had starred pretty much the whole thing, the way other people mark up the Tao Te Ching or Letters to a Young Poet. Many of the notes were wonderfully open to interpretation; they made sense if you applied them not just to filmmaking but to life: “The point is not to direct someone, but to direct oneself.”

But it wasn’t until years later, when I started to take seriously the craft of cooking, that I realized the real value of Bresson’s Notes as a kind of Art of War for the kitchen.

Until then, I’d heeded the advice of one laddy mag or another and nailed down a couple of go-to dishes I could rely on for dates—risotto with [x] and omelets with [y]—but I didn’t yet have a real feel for the kitchen, and as I found myself bookmarking more ambitious projects in my growing cookbook collection, the wisdom in Notes on a Cinematographer kept me grounded.

“A whole made of good images can be detestable” was instructive when I made my first (very dry, bland) paella. As countless doomed soufflés became egg sandwiches, I comforted myself with Bresson’s belief that “a thing that has failed can, if you change its place, be a thing that has come off.” Then again, sometimes there was no way to save a dish. “A single movement that is not right,” such as, say, too much cumin in the black bean soup, “gets in the way of all the rest.”

As I spent more time in the kitchen, I saw that to “put oneself into a state of intense ignorant curiosity, and yet see things in advance,” was what cooking was all about. “Everything escapes and disperses.” The cook must “continually bring it all back to one,” a holistic singularity, a meal. Whenever my inattention resulted in the butter burning or the pasta overcooking, I remembered Bresson’s injunction: “Dig deep where you are. Don't slip off elsewhere. Double, triple bottom to things.”

Gradually, I improved at making do with what I had on hand. Grating market-fresh beets to use as a condiment on a sandwich, or roasting them to put in a salad, demonstrated that “a small subject can provide the pretext for many profound combinations.” At other times the best ingredients needed nothing but to be eaten, and with a fresh pluot or pear in hand I remembered to “be sure of having used to the full all that is communicated by immobility and silence.”

That rigorous paring down is the most important thing I’ve learned from Bresson. Cooking is as much about taking away as it is about adding; it’s good to remember the concept of plenitude and to let the inherent flavor of something speak for itself.

Or, in Bresson’s words, to have the wisdom “not to use two violins when one is enough.”