Most food manufacturers start small, and if they expand into industrial-scale production they don’t turn back. Then there’s the Koeze Company. The family-owned, 83-year-old peanut butter producer went from small to big and then back again—deliberately taking a huge drop in sales in order to focus on quality and tackle the high-end market. Its story is a window into the trials that face a small manufacturer trying to turn back the clock on the food industry.

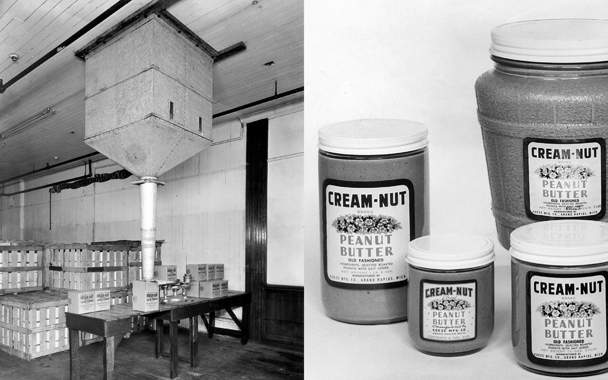

When Sibbele Koeze founded the Koeze Company in 1910, six years after peanut butter was introduced at the Universal Exposition in St. Louis, the company sold only manufactured goods like salad dressing and vinegar. Koeze began making peanut butter in 1925, at a time when, according to current company president Jeff Koeze, “there were literally hundreds upon hundreds of small manufacturers” around the country who sourced their peanuts from throughout the South. This abundance of local PB producers didn’t last: Thanks to the effects of agricultural and production industrialization, and the Depression—during which peanut butter was marketed as an inexpensive source of protein—peanut butter became just another mass-produced food.

“That was a train we rode for quite awhile,” Koeze admits, referring to the more than two decades that his company churned out peanut butter on an industrial scale. But in 2000, he felt the time was right to re-introduce the product “with the right packaging to the right kind of consumers.” His father, he adds, had long been frustrated with the unwillingness of industrial peanut butter buyers to consider anything but cost, causing quality to pay the real price.

Leaving that market was, Koeze says, “a huge risk”—two thirds of the company’s total sales came from peanut butter. But his strategy, “to get a higher-quality handmade product into the hands of people who appreciate it,” worked. While sales did fall by two thirds, the company kept its profits constant by working to increase from its chocolate and nut mail-order catalogue.

But making a product the old-fashioned way comes with its own modern problems. First, there’s the issue of finding the 1940s-era machinery that Koeze uses to roast, grind, and blanch its 300-pound batches of peanuts. “It’s virtually impossible to find new equipment in the right size,” says Koeze. “As food products became industrialized, the equipment went from being able to make small batches to making huge quantities.” He likens the search for vintage machinery—at auctions, over the Internet, through a scattering of dealers—to the hunt for classic car parts. The company spent two years seeking out and restoring the equipment to make its new, crunchy peanut butter, which is scheduled to debut in January. (The crunchy variety is made by dicing the nuts in one machine, and then blending the diced nuts in a controlled way into the peanut butter with a second special machine.)

Then there’s the problem of finding good peanuts. “There’s no consistent quality from a single farm unless you’re the luckiest farmer in the world,” Koeze says. He adds that for Koeze’s new organic variety, Virginia peanuts weren’t even an option, since the company couldn’t find an organic grower.

Making artisanal food in a non-artisanal world is anything but a quaint endeavor—and that’s one reason, Koeze says, why so many specialty food makers “go astray,” leveraging specialty-store recognition into high-volume sales at large grocery chains.

He adds that around 2 percent of his company’s $10 million total annual sales comes from peanut butter. “I’m guessing this year we’ll make 100,000 jars,” Koeze says. “When people from Smuckers”—which churns out 250,000 jars of Jif every day—“read that, they’ll laugh.” But, he admits, back in the old days, when 100,000 jars of peanut butter were merely a couple days’ work for the Koeze Company, “we would have laughed, too.”

Pinterest

Pinterest