My friend Patricio writes some of the best wine tasting notes I know of. They are peppered with tactile sensations: round, crispy, crunchy, velvety, sharp, furry, silky. They sound like he’s really tasting the wine, rolling it around in his mouth, enjoying it, taking it all in for the pleasure of it.

Texture doesn’t play much into the wine tasting lexicon; the Court of Master Sommeliers and other official wine study organizations hew to a strict protocol that focuses on more quantifiable aspects such as color, fruit flavors, acid, alcohol, concentration, and length of finish. It’s an attempt to make a subjective act more objective—useful when you’re blind-tasting a wine and trying to figure out what it is, but entirely missing the point when enjoyment is the object. Who cares whether it tastes like red currants or more like red cherries? The essential question is whether it makes you happy or leaves you feeling abused—beaten down by buckets of overripe plums, scratched up by acidity, or sucked dry by tannins.

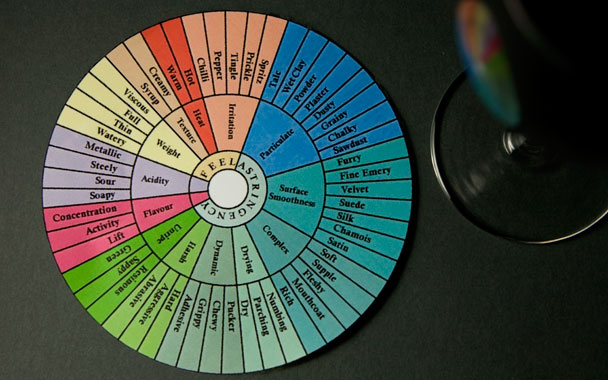

Now there’s a reference for wine texture. Gary Pickering at Brock University in Ontario, Canada has come up with the White Wine Mouthfeel Wheel, inspired by the lesser-known mouthfeel wheel for red wines that a team of Australian researchers developed in 2000. Pickering, who specializes in the psychophysics of taste—that is, how we perceive physical stimuli—put nose clips on his subjects so that aroma and flavor wouldn’t inform their perceptions, and had them taste 71 white wines. Any terms used more than four times by more than one panelist became candidates for the final lexicon; the panelists then developed definitions for each term, running off to the local grocery or Wal-Mart to find velvet, foam, felt, marshmallows (small and large), chocolate mousse, eggs, fruit punch, aluminum foil, and whatever else they might use as a reference point.

In the end, they came up with 54 texture descriptors. Smoothness is broken down into silk, satin, and chamois; what they call “mouthcoat” (I’d call “body”) is divided into baby oil, sunflower oil and olive oil, and so on.

Like the Wine Aroma Wheel developed by former UC Davis professor Ann C. Noble, a mouthfeel wheel seems ridiculous if taken too seriously. Texture, like taste, is a personal thing; what feels like satin to me might feel rougher—like fine emery, to choose from the wheel—to someone more sensitive to acid, alcohol, tannins, or any other aspect that affects texture. The wheel also plays up the importance of experience. I couldn’t figure out what the difference might be between “fresh meringue” (defined as 2-3 egg whites beaten to stiff peaks) and “whipped cream” until I whipped up some of each. Whipped cream has a—duh—creamier feel, and sticks to the tongue longer.

Useful? For scientists, sure: a common vocabulary helps them talk about and qualify the interaction of physical components of wine and human perception, like, say, how certain elements affect the perception of viscosity and density of wine. Now, when someone in Pickering’s lab says a wine feels like velvet, everyone there will know what he means.

For the rest of the wine-drinking world, I doubt the mouthfeel wheel is going to have much (if any) impact, but it did inspire me to try something new, to notice something I hadn’t before. Maybe it’ll help me become as good at describing wine as Patricio. Or maybe I’ll just enjoy my wine more.

Pinterest

Pinterest