My first trip to Paris was anything but glamorous. I was traveling with the lowest, least desirable company a 15-year-old boy can imagine for himself—his parents. My budget-conscious father had booked us on one of those package trips that combined London and Paris for a price that sounded too good to be true, as indeed it proved to be. The less said about the damp, foul-smelling hotel on the outskirts of London, the better. The hotel in Paris was also run-down and odoriferous, but the blue Art Deco tiles in the small lobby hinted at a grander past, and from the window of my parents’ room we had a view of the Place Pigalle and the rooftops of the 18th arrondissement.

Now the haunts of Jean-Paul Gaultier and Johnny Depp, Pigalle at that time was best known for prostitutes and petty crime, and despite its proximity to Sacré-Coeur, the place horrified my parents. But thanks to my reading, I had a nascent case of nostalgie de la boue, and the seediness of the area was redolent of bohemian romance. My parents’ mortification and my fascination converged at the moment I was accosted by a prostitute in the Place Pigalle. She grabbed my arm as I was walking toward the hotel. There ensued a brief tug-of-war, my mother pulling one arm and the prostitute pulling the other. It must have been one of the more traumatic events of my mom’s life, but I saw it as a seminal moment in the development of my sensibilities. I couldn’t help being beguiled by my near brush with Eros.

More predictably, perhaps, I also discovered wine and food in Paris, although not at a restaurant; the few experiences I remember of dining out there were awkward and embarrassing. This was a time when Parisian waiters delighted in torturing tourists. I had assured my parents that I spoke passable French, but my attempts to communicate elicited blank stares or sneers. Our one experience with a Michelin-starred restaurant was a disaster. We ended up ordering the few items we recognized, grateful as Dickensian orphans for the favor of being served, and fled as soon as we were able. Partly because of that experience and partly because of my father’s thrift, we decided on our second full day to buy lunch at a little grocery and eat in the hotel. The simple snack of bread, cheese, and red wine was one of the best meals I’d ever eaten. The cheese was something like Comté, the bread was crusty and soft within, and the wine, which cost three or four francs, might have been a Beaujolais or a Côtes du Rhône—it was robust and dry and perfect with the cheese. Paris became, in my mind, inextricably associated with sensual pleasures, although I harbored a vestigial fear of “fancy” Parisian restaurants.

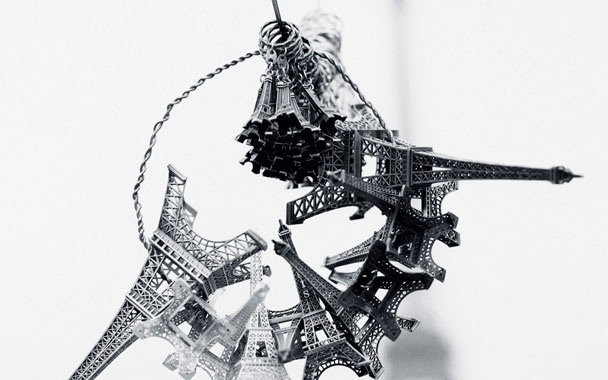

It would take me more than a decade to return to Paris, but I returned on a triumphal note, for the publication of my first novel. This time I stayed on the Left Bank, at the ancient Hôtel de l’Abbaye. I discovered foie gras, in its cold-terrine form, on my first night and ate it at every subsequent meal in a series of bistros. On the last night of my visit, as a reward for my promotional work, my publisher sent me to the three-star Lucas Carton. Facing the prospect with some trepidation, I invited a pretty journalist who had interviewed me to come along and discovered that foie gras was also wonderful in its hot, sautéed form. I wish I could remember all the dishes we ate. It was certainly the most exciting meal I’d ever had, and the bottle of ’79 Gruaud-Larose cast a rosy glow on the whole evening. The service was efficient and helpful, almost obsequious. The room was beautiful. I felt lucky. My first three-star experience was magical, thanks in part to my dinner partner, who did nothing to change my perception of Paris as a city of erotic intrigue. We walked back to my hotel via the Eiffel Tower, which is much more romantic at night.

Pinterest

Pinterest