Ask any immigrant what she misses most about her homeland and she’ll undoubtedly say the food. This is especially so for villagers accustomed to fishing, farming, and hunting their daily meals. Everything changes on arrival in a new land. Chicken is no longer a feathery alarm clock clucking in the yard—it’s five boneless breasts on a Styrofoam tray. Pig? The squeal is long gone by the time it reaches an American plate. Gone, too, is the shaman’s garden, which grew the medicinal herbs to heal injuries and disease. The years pass, and the kids opt for McDonald’s and donuts. A deep sense of loss festers in some kitchens—until a budding young cook steps up to record the recipes of her ancestors.

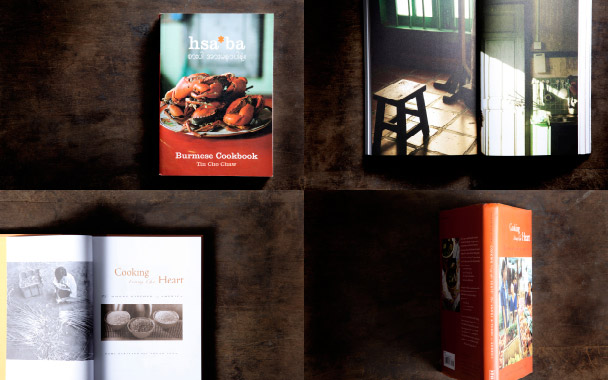

When that happens, we’re all better chefs because of it. In recent weeks, two stellar cookbooks have arrived on my kitchen shelf. Has*ba (order off the author’s website, $31), by Tin Cho Chaw, is a pretty little paperback with colorful photos and 100 detailed Burmese recipes from the relatives she left behind after moving to England at age 8. “Growing up in a quiet town in Devon, I missed the familiar, comforting food of my childhood,” Tin Cho Chaw writes. “This was when I began to develop a keen interest in cooking Burmese food.” The book, which means “please eat” in Burmese, combines recipes with the author’s personal tips for preparing and eating traditional foods, and her relatives’ “unspoken secrets that make a particular dish outstanding.” She also offers cultural insights and explanatory notes. I love it when I feel smarter after reading a cookbook. I never knew that a tiger prawn’s head contains a tiny drop of yellowish-orange oil, “like gold dust,” that’s used to infuse Burmese curry with intense flavor and color. And although I haven’t recently had a baby, I can’t wait to taste her sticky rice with chicken, a “hot” dish with ginger and rice wine served to women in the one-month “confinement period” after childbirth.

No surprise, maternity food also centers prominently in Cooking from the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America (University of Minnesota Press, $29.95). “The most important role for a traditional Hmong woman is motherhood,” write co-authors Sheng Yang and Sami Scripter, who include in their book a chicken soup for new mothers, a “medicinal chicken” for healing injuries, and other recipes for life’s milestones—weddings, births, funerals, and celebrations. Yang was born in Laos and immigrated to the United States with her family in 1979. Scripter was her neighbor and partner in the kitchen. Together, they have created the first thorough record of Hmong culinary traditions. “Writing things down felt important because no comprehensive written record of Hmong cooking seemed to exist.” Not only do readers get recipes, but the poetry and personal narratives of Hmong people living across the United States. While Tin Cho Chaw, Sheng Yang, and Sami Scripter cannot physically transport their readers to Asia, they triumphantly bring the heart of their kitchens to the Western table.

Pinterest

Pinterest