Unfortunately for Michael Steinberger, his new book, Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine, and the End of France, was published after its sell-by date. (See “Good Living Travel Q&A,” page 38, Gourmet, July 2009.) The main idea for the book is that the food and wine of France aren’t what they used to be. But Gourmet wrote on this subject almost a decade ago in an article by French food critic François Simon, and Adam Gopnik similarly signed off on the subject for The New Yorker with his 1997 article “Is There a Crisis in French Cooking?”

Though ultimately Steinberger back-peddles a bit on his piquant subtitle by judiciously concluding that France actually does produce some pretty good food and wine, and that new gastronomic movements like bistronomie may in fact be creating a new rush of creativity in old Gaul, I doubt he’s totally in synch with Simon, whose lively, amusing, and insightful new book Pique Assiette: La Fin d’Une Gastronomie Francaise (Grasset, in French only) examines the same turf from a French perspective. (A pique assiette, by the way, is a freeloader, a wry reference to the complimentary meals many French food critics scrounge through their profession.)

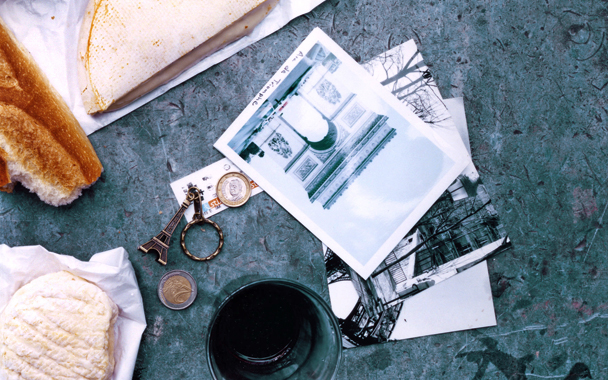

Simon, food critic for Le Figaro and probably the most feared and respected gastronomic writer in France, observes: “Foreign journalists regularly come to the bedside of our gastronomy, take the pulse of our great chefs, examine the gizzards of our markets, and depart in a storm of disastrous clichés—the end of the bistro, the mummification of our grandest tables, the disappearance of our best products, etc. These conclusions aren’t necessarily false, but for anyone who goes a step further, there’s a France that’s brimming with new delicacies, a country that’s filled with astonishingly talented young chefs, and a thriving cuisine. Everywhere you find superb baguettes and quite sincerely one has never eaten so well in France.”

To be sure, there are many things about the current condition of gastronomy in France that Simon finds appalling. Like Steinberger, he hates the idea of the commuter chef (Alain Ducasse and Joël Robuchon are specifically cited). He is mistrustful of the molecular cuisine championed by the Spanish, thinks the Michelin guide has had a decidedly pernicious effect on the French kitchen (“When one wants to find a dull restaurant in the provinces, one looks for the local one star”), accuses France of such an “extreme self-satisfaction that the whole world is excluded,” and rails against the menace of mediocrity.

Happily, however, he says, “another generation has arrived,” one that understands that “gastronomy had become a baroque principality” and is ready to set it free. So in the end, both Simon and Steinberger reach similar conclusions. Where they differ is that Steinberger now sees France as but one of many countries where you eat well, whereas Simon makes a hopeful but well-reasoned case for the likelihood the country will retain its historical culinary pre-eminence.

Pinterest

Pinterest