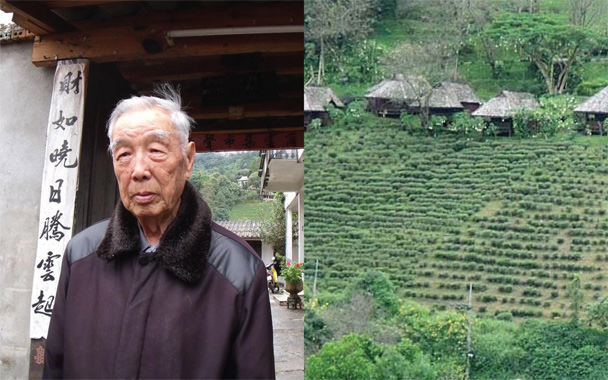

The general is tall and thin, with silver hair and wild, wispy eyebrows that fly from his face like a set of wings. He sits before the windows of a concrete room painted mint-julep green, wearing a brown winter jacket with a fur collar that rings his wrinkled face. It’s cold up here in the mountains along the Thai-Myanmar border; wintry air invades the general’s home.

Lue Ye-tein, 92, is known for soldiering. He fought in Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT) army against Mao Zedong. Later, he was instrumental in defeating Thailand’s Communist insurgents. But first, before any talk of war, he offers tea—a pale, peach-colored oolong grown in his garden. “The plant is from Taiwan,” he says. “The Taiwanese government gave the plants to the people here to help us grow them.” Tea is key to General Lue’s story.

The “Lost Army,” as the general and his comrades were known, fled Yunnan in 1949 as Mao Zedong took victory in China. The men and their families spent a decade in Burma’s jungles before taking refuge in the mountain village of Mae Salong, Thailand. The Thai government granted the soldiers asylum in exchange for protection against Communist insurgents—an agreement that kept the general’s army fighting for another 20 years. It wasn’t until the early 1980s, after innumerable battles, that Thailand’s Kuomintang soldiers could rest in relative peace. “My whole life was always walking and climbing mountains and carrying guns,” General Lue says.

War was what the Kuomintang knew, and so was opium. Although General Lue doesn’t address this issue himself, Mae Salong long had the reputation of an opium-growing haven. As General Tuan Shi-wen, Lue’s predecessor, told a 1967 journalist in an oft-repeated quote: “We have to continue to fight the evil of communism, and to fight you must have an army, and an army must have guns, and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains, the only money is opium.”

When war ended, the Thai government encouraged the soldiers to grow alternative crops. Tea proved a useful contender. Not only could it make money, Lue says, but “we used the tea as an excuse to make contact with Taiwan,” home of the KMT headquarters. General Lue knew nothing about tea before the Taiwanese government invited him to the island, to see how the plant grows. He discovered he actually liked the taste of oolong, and he returned to Thailand with seeds that would change Mae Salong’s economy.

The former soldiers were given 200 plants each, “to go and help themselves,” General Lue says, and the industry spread from there. Today, village plantations and family growers produce the majority of northern Thailand’s tea; exports go to China and other countries in the region. Tourists now ply the narrow mountain roads leading to the tea-lined streets of Mae Salong.

This is a little piece of China in Thailand, with Mandarin as the most common language and Yunnanese pork a perfect reason to stay for dinner. Mae Salong now ranks among the area’s top tourism destinations. This pleases General Lue, who has turned a former soldier’s training camp into the Mae Salong Resort.

“I’m not a soldier anymore,” General Lue says, as steam wafts from glasses of his home-grown tea. “That’s all history.”

Pinterest

Pinterest