It began innocently enough. “I’d like the ñoquis, please,” said my new friend Leo Miño, a 41-year-old public defender, as we sat at Don Chicho, one of the city’s countless old-school pasta joints. I already had my eye on the sorrentinos, huge ham-and-ricotta-stuffed ravioli being shaped expertly by the tiny nona sitting at an equally tiny table just inside the entrance, so I almost missed the waitress’s response. “Martes,” she said. Leo nodded comprehendingly.

“Martes?” I asked. “They only serve gnocchi on Tuesdays?”

“Yes,” said Leo, just as his old schoolmate Guillermo Katz, an English teacher and expert on all matters porteño (Buenos Airean), chimed in, “No. In Buenos Aires, we only eat ñoquis on the 29th. And that’s this coming Tuesday.”

“But why the 29th?” I asked. They looked at each other in silence for a full minute, then shrugged in unison. “We don’t know,” Guillermo admitted sadly. (He wasn’t used to not knowing things.)

“Then let’s find out,” I said, smiling at the idea of a challenge.

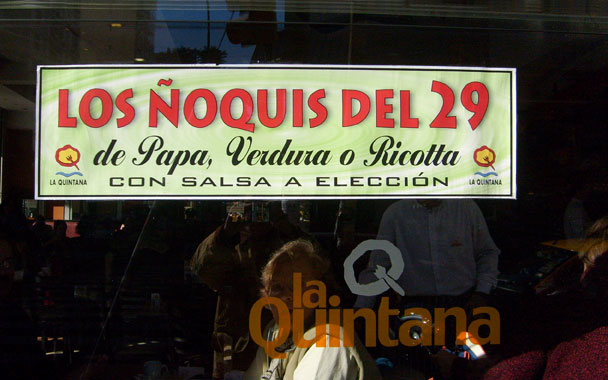

Over the next few days, Buenos Aires came down with gnocchi fever. Every Italian restaurant in the city—and in a city where the gossip rags are peppered with names like Guillermo Coppola, Dolores Fonzi, and Martín Palermo, that’s quite a few restaurants—had a handwritten sign in the window saying “Tenemos ñoquis el 29.” It was hard to believe that supply wasn’t outstripping demand.

“Claro que no,” said Sergio Feldman, a 37-year-old PR executive. “We all love them. Me, I eat ñoquis on the 29th of every month.” “But why?” I asked. “Where does the tradition come from?” He paused. “No lo sé.”

Next! “Ah yes,” said 71-year-old pensioner Isabel Binsenzwald knowledgeably. “Of course. It’s a Genovese tradition, brought over by Italian immigrants.” Overhearing her, Alejandro Logegaray, a fiftysomething engineer, shook his head vehemently. “Absolutely not,” he said. “It’s not Italian at all—it’s Uruguayan. We borrowed it from them.” Ana Laura Lusardi, a 34-year-old makeup artist, jumped into the fray. “We didn’t borrow it from anyone,” she said hotly. “It’s an old Argentinean tradition, because in this country you receive your paycheck just once a month, around the 29th. So when you get the bill for the ñoquis, you leave your money under the plate, and it brings you financial luck until your next payday.” “Hardly!” cried Juan Lucangioli, a 29-year-old musician. “You’ve just been paid, so who needs luck? You’re eating ñoquis to celebrate. And anyway, it’s a new tradition. People have only being doing it for the past ten years.”

I was getting nowhere. Clearly, it was time to consult the experts. On the morning of the 29th, bright and early, Guillermo and I placed a call to El Obrero, a working man’s canteen that enjoys cult status amongst porteños and savvy foreigners alike. “Tienen ñoquis?” we asked. “What do you mean, do I have them?” came the answer. “I’ve been kneading them since six this morning!”

That was all we needed to hear. We hopped in a cab and headed for rough-and-tumble La Boca, the old Italian quarter of Buenos Aires. The city may be the Milan, Paris, and Rome of South America, all wrapped into one, but La Boca is its Naples, which means that if your cab driver doesn’t know precisely how to get to El Obrero, find another one—or else be prepared to scour the area’s meaner backstreets until you find fleet of new BMWs crowded onto a decidedly vintage-Chevy kind of block.

Safely ensconced at a back table, we hatched our plan: order two plates of ñoquis and prepare for enlightenment. Just before we placed our order, we learned that our server, Francisco, had been at the restaurant since it opened in 1953. He boasted the particular brusque charm of the career waiter—the man who knows everything there is to know and just may impart his secrets—provided you, the patron, avoid irritating him before he’s done so.

Francisco being Francisco, he refused point-blank to bring us two orders of ñoquis, insisting that I try the handmade spinach ravioli instead. (And, Francisco being Francisco, he was right—unlike the tiny Parmesan- and mozzarella-stuffed ravioli, the ñoquis weren’t particularly tender or flavorful. Not that it mattered—the food at El Obrero is quite good, but even if it were abysmal, you’d still pledge your undying love for the place.)

Deeming the moment right for a little gentle detective work, Guillermo brought out the soft soap. “So how long have you been serving ñoquis?” he asked casually. “Oh, ever since I started here,” came the answer. “Ah,” said Guillermo. “But just on the 29th, right?” “Claro,” said Francisco, looking puzzled. “Saben porqué?” Guillermo continued. But here we had clearly crossed the line, and Francisco’s patience snapped. “I’m very busy right now,” he said stiffly. “If you have questions, call tomorrow.”

Thus dismissed, we headed for another La Boca institution, Il Matterello, the elegant Sigourney Weaver to El Obrero’s scrappy Melanie Griffith. There we were greeted with a regal nod by dueña Carmella Manfredini, who moved to the neighborhood from Bologna in 1947 as a young girl. Like every other item on the menu, she explained in pitch-perfect Italian, her gnocchi are made from scratch. They were a dream, pillowy and tender.

And yet, over espresso and housemade limoncello, it emerged that while Carmella could certainly feed us, she couldn’t help us. “I’d never even eaten gnocchi before moving here,” she confided shyly. “I first tasted it here, in La Boca.”

“On the 29th?” I asked with a sigh.

“On the 29th.”

Leaving our bills under the plate, we stumbled home, where I swore I would never take another bite of ñoquis again. Gnocchi Day had beaten me, and I was none the wiser for it. Guillermo took that moment to chuckle under his breath. “What’s so damn funny?” I growled. “Aaaa! Do you know what I forgot to tell you?” he said with glee. “Ñoquis aren’t just food. They’re people, too. They’re what we call the kind of bureaucrats who are on the payroll but don’t actually work. They turn up just once a month to collect their paychecks…” “Just like the ñoquis,” I finished.

Normally I would have found this tidbit fascinating, but I was too irritated—and far, far too full. “How is it possible that no one knows where this damn tradition comes from?” I yelled at Guillermo. “I’m fed up! I’m stuffed and I’m fed up! I’m never eating gnocchi again!”

But I was underestimating the power of Gnocchi Day. At 11 P.M., appetite and good spirits restored, Guillermo and I headed to Casa Cruz, in the glamorous Palermo Soho district, for dinner. (Such is the popularity, or ethos, of Casa Cruz that even with a reservation, we had to wait for our table—not a common occurrence in Buenos Aires.) At first glance, the restaurant seemed to have been imported lock, stock, and attitude from Manhattan’s Meatpacking district, the kind of hotspot where, or so it would seem, food is the least of the attractions. But a refreshingly tart cassis cocktail quickly raised my hopes. “Ooh,” I thought, “Foie gras brulée. That looks fantastic. And poached oysters! And look at the pastas. Oh… no…” There it was: Gnocchi. Was I mad? Did I just plain not know when to quit? Yes on both counts, but I couldn’t resist. And, as it turned out, I shouldn’t have. Laced with crisp bits of morcilla, or blood sausage, the gnocchi were phenomenal. Better still? Like the mystery itself, they’re on the menu all month long.

Casa Cruz Uriarte 1658 (011-4833-1112)

El Obrero Agustín R. Caffarena 64 (011-4362-9912)

Il Matterello Martín Rodríguez 517 (011-4307-0529)