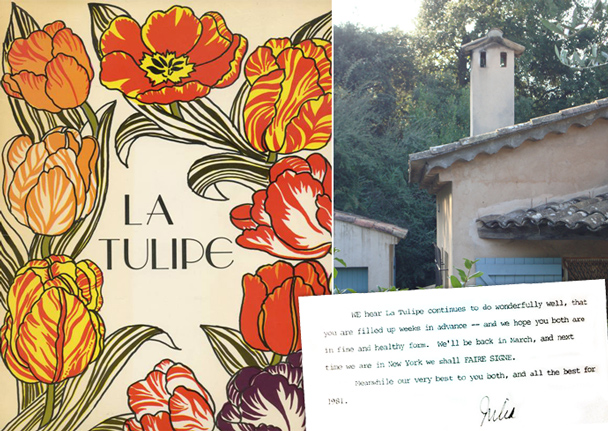

It was the spring of 1980, and La Tulipe, the little restaurant my husband, John, and I owned in Greenwich Village, was still overflowing with more customers than we could seat. Not quite a year had passed since we'd earned three stars from Mimi Sheraton, the New York Times restaurant critic, just six weeks after our May 1979 opening. "Your phone will not stop ringing for five years," advised Leon Lianides, owner of the nearby Coach House restaurant—a Greenwich Village legend and now the site of Mario Batali's Babbo—when he called to congratulate us on the review.

I was the chef, and my husband, John, formerly a noted minister and schoolmaster, was up front. During the evenings, my kitchen doors often swung open unexpectedly, and John would be there with a customer in tow. Many times it was a celebrity who had loved the apricot soufflé or lamb chops and was then encouraged by my husband to "tell her yourself." That's how I met Julia Child for the first time.

Julia was such a charmer, I soon forgot how I looked in my food-stained apron and messy hair after hours of cooking on the line. She shook hands all around and asked questions of the young kitchen staff—mainly C.I.A. graduates—who all were thrilled by her surprise visit.

She had adored her garlic chicken and wanted to tell me in person. "You can always tell a really good cook by the chicken she roasts," she wrote me years later, recalling that night.

Julia and I immediately hit it off, and as we chatted, she asked if we had made any vacation plans for when the restaurant closed in July. I mentioned that we were thinking of going to France, and she stunned me by immediately suggesting we stay in her house in Plascassier, a small village near Cannes.

"Is that a serious offer?" I asked incredulously.

"It certainly is," she replied. "Paul and I will be traveling."

That was an offer we could not refuse.

The day we arrived at La Pitchoune—the Childs' name for their Provençal cottage, meaning "the little one"—we had no sooner set our bags down on the stone terrace to breathe in the scented air and admire the olive trees, the mimosa, the neighboring vineyards, and the house itself, with its red-tile roof and long wooden shutters, when the phone rang. It was Simone Beck, the Childs' neighbor and one of Julia's co-authors of Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Simca, as she was known, was calling to invite us to a garden party that evening on their adjoining property, Domaine de Bramafam.

For a moment, I imagined the party was for us—a neighborly welcome to La Pitchoune—but I was soon told that the guest of honor was none other than Escoffier's nephew. John and I were jet-lagged, and John was in no mood to socialize, but the foodie in the room could not say no to meeting an Escoffier—and in Simca Beck's garden, no less.

It was a gala affair, with lanterns and white-coated waiters serving Champagne and Simca's tasty hors d'oeuvres. There were restaurateurs and chefs and, of course, Escoffier's nephew. I hate to admit I have no memory of the nephew, but I do remember the heated disagreements—in French—about restaurant ratings in the Gault Millau guide. If, instead, it had been the Zagat guide being trashed, and in English, the setting could have been the Hamptons, and Plascassier just a dream.

John was determined not to let our stay at La Pitchoune turn into a busman's holiday, because there was so much to see and rediscover since our last trip to France. But on rainy days too nasty to be out and about, I was "allowed" to be in the cozy kitchen, baking pastry for a fruit tart, or putting Julia's shiny copper pots to use making something good for dinner. Once I was about to roast a nice plump chicken—in our absent hostess' honor—but we couldn't figure out how to light the oven. That's when we remembered the "Black Book." In the months leading up to our visit, a flurry of letters had been exchanged between the Childs and the Darrs, with Julia reminding us more than once about the "Black Book" and where to find it. It had all the answers, she said, to any problems we might have during our stay at La Pitchoune. Sure enough, the answer was there. It began: "TO LIGHT THE OVEN: Lie down on the floor." Hilarious, but it worked.

John and I loved exploring the surrounding villages on their market days, and the long wooden table in Julia's kitchen became cluttered with artichokes, lettuces, wild herbs, and much more of Provence's beautiful summer bounty. I also had my eye on Julia's large marble mortar and pestle, which sat on the floor near the kitchen door, and I just had to find an excuse to use it.

As it turned out, the opportunity came when we invited the Fischbachers (Simca and her husband) along with four of their houseguests to lunch on La Pitchoune's terrace. I planned to do a butterflied sea bass and mushroom dish that I was going to put on La Tulipe's menu when we returned to New York. We drove to Nice for the fish and found the market, which had always been bustling in previous visits, almost empty. Unbeknownst to us, there was a strike occurring that day. The fish section of the market looked surreal with so few people and no fish in sight. We searched the market anyway, and in a stroke of luck, discovered that the only fish to be had were hidden in barrels: beautiful shiny sardines. We bought a few pounds and spent hours cleaning them. I prepared them en escabeche (lightly sautéed and then marinated) as the appetizer.

Under the circumstances, I abandoned my vision of the sea bass and chose instead to make the main course a soupe au pistou, the hearty Provençal vegetable soup similar to an Italian minestrone. How could I have considered any other dish, I wondered, as I admired the green finger-length zucchini and yellow squash, the leeks and luscious tomatoes, the white beans so fresh they needed no soaking, the fragrant basil, and the bright blue-and-gold can of Alziari's olive oil that we'd gathered in Nice, all spread out on the long kitchen table.

What makes soupe au pistou so special is the pistou—a pesto without nuts—that you add to the soup just before serving. Pistou is magical in how it turns a simple vegetable soup into something totally different and infinitely more wonderful. What better excuse did I need to use Julia's mortar and pestle? Crushing handfuls of the basil and garlic with oil with Julia's pestle took a lot longer than grinding it in my food processor, as I usually did, but speed was not a factor here. Even though I don't have a single cooking friend who owns a mortar and pestle or would consider making pesto in one, I just loved mashing the pistou in that mortar. The resulting thick purée was a revelation, and the soup was exceptional.

Dessert was a strawberry tart. Pastry has always been what I do best; as James Beard once told me, this is because I have cold hands. A thin layer of pastry cream covered the baked shell, and beautiful strawberries from nearby Carpentras—famous for its fraises—topped the cream.

I'll admit I was a little nervous about cooking for Simca Beck, but I was pleased with how the lunch turned out. As the Fischbachers were leaving, Simca told me that Richard Olney, the American food writer who lived in Provence and was best known for his French Menu Cookbook and Simple French Food, had visited them the week before. "He did soupe au pistou," declared Simca. I've never been sure if she was implying that Olney's version was better, but happily I'll never know. That would spoil my memory of meeting Julia, and of our perfect stay at La Pitchoune, complete with bragging rights to bathing in the same narrow tub Beard got stuck in on one of his many visits.

Sally Darr started out as a textile designer, but a passion for cooking led her to the test-kitchen staff of the Time-Life Foods of the World series, and in 1969, at James Beard's suggestion, to the Gourmet magazine test kitchen as the food editor. Ten years later, she and her husband opened their own restaurant, La Tulipe, in New York City, which ran successfully for 12 years.