Tap picture to advance the slideshow.

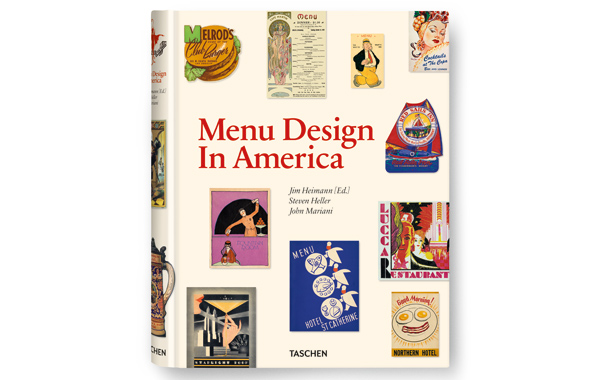

If Jim Heimann had lived in Renaissance Europe, he’d surely have had a private museum of curiosities, containing dodo eggs, unicorn skulls, and the like. Since he was born in mid-20th-century California instead, he has a museum-quality archive of curiosities of a different kind, relating to Americana of all sorts, including car culture and the history of design. Heimann’s collection includes printed materials, original photographs, artifacts, and, by no means least, some 5,000 menus, representing high-end restaurants, roadside stands, and everything in between. Heimann is a lecturer, pop anthropologist, designer, executive editor at Taschen America, and now editor of Menu Design in America: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design 1850–1985, a magnificent large-format, three-language, 400-page survey by Steven Heller and John Mariani of this surprisingly profound subject.

Standing in his labyrinthine Los Angeles archive, surrounded by boxes of meticulously catalogued menus, Heimann explains to me that the book’s final form took some time to determine. “Initially, we thought we might do menus of the world, but the American material was so rich, we knew we had to focus.” His own collection was always meant to play a central role, and it was supplemented by archival material from the Culinary Institute of America and the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University, among other institutions. “But it turns out there really aren’t that many collections," Heimann notes. "So we started looking for individual collectors, and then somebody said, Well, you know, the best menu collection in the world is right around the corner from you in L.A.”

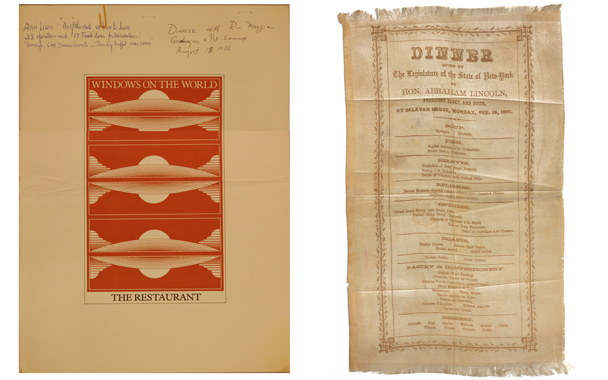

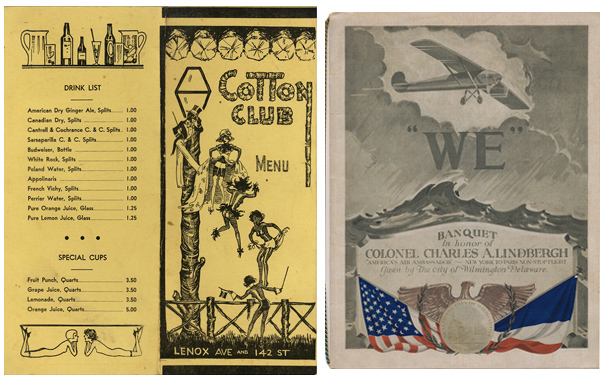

On making contact with this collector (who still wishes to remain anonymous), Heimann found him very welcoming and his holdings a revelation. “It trumped all the other collections,” says Heimann. “I handed him a wish list. There were key menus I was looking for, such as the Lindbergh dinners after his transatlantic flight. I knew there was a dinner in Paris, and I knew there must have been one in New York, and when we met this collector, he said, ‘Well, which one do you want?’ It turns out there were 40 of them. After Lindbergh came back from Europe, he barnstormed across the country and they had dinners in 40 different cities.” Three examples made it into Menu Design.

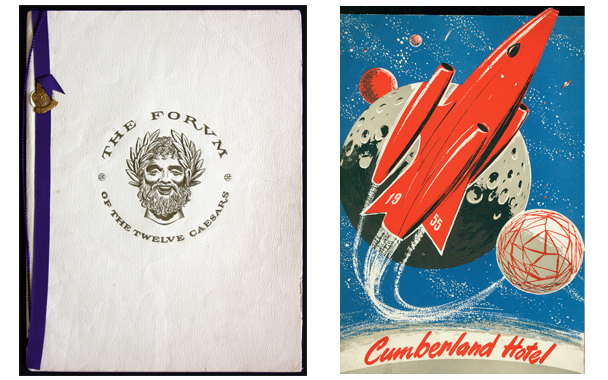

By necessity, Heimann acknowledges, “the book is in part ‘the best of,’ but I also wanted to tell a story. Once I saw the scope of what was available, I realized there’s clearly a tale here of American eating.” In fact, the book contains a double narrative, of the menus’ form and content—that is, the food they offered. Some readers will focus primarily on the beauty of the designs—the extraordinary convergences of color, illustration, and typeface. There’s the cover of a wine list from the Burlington Route railroad that I find just exquisite. Readers may also be amazed and amused by menus in the shape of pigs, crabs, bunches of bananas, or conga drums.

Other readers will prefer to regard the menus as social documents. One of the earliest in the book dates from 1861, documenting a dinner given by the New York State Legislature for President-elect Abraham Lincoln; terrapin soup and larded grouse were among the options. Toward the end of the book is a menu from Windows on the World, which crowned the North Tower of New York City’s World Trade Center before it was destroyed on September 11, 2001. Both artifacts are reminders that something as simple as a menu can have tremendous resonance.

Pinterest

Pinterest