What are you having for lunch today? Street-cart falafel or Indian takeout? What about dinner tonight? Think you might splurge on pad thai and tom yum goong soup or slender slices of yellowtail sashimi? In today’s culinary landscape, eating and thinking globally is taken for granted, but it wasn’t always the case. Just how did we make the jump from corn dogs and cotton candy to sashimi and Sangria? For clues, look no further than Queens, New York, the site of the historic 1964 World’s Fair.

Before 1964, Continental cuisine (read: French) reigned in the United States with restaurants like Le Pavillon, Lutèce, and La Grenouille epitomizing fine dining, while American palates were just learning to love lo mein. Home cooks angling to be cosmopolitan simply had to perfect a spinach soufflé and name-check James Beard. But there were stirrings of a revolution. Julia Child’s high-spirited French Chef premiered in 1963, taking the hoity-toity out of French cuisine, while New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne was turning readers on to paella and cilantro.

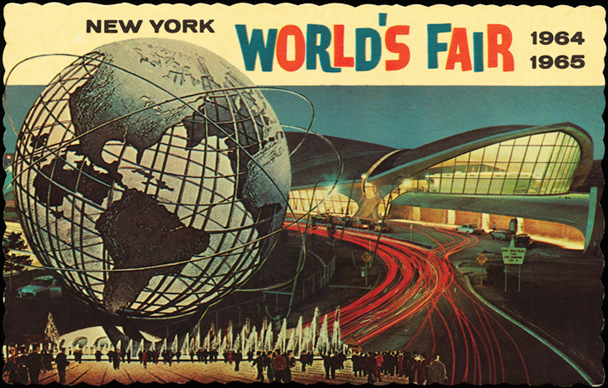

Into this nascent foodie scene came the World’s Fair, a messy affair muddled by mismanaged funding and political infighting—the sort of things that would never muck up a civic project in our current, enlightened times—wink, wink. Robert Moses, the infamous New York City urban planner in charge of both the 1939 and 1964 fairs, gave pride of place to the World of Food pavilion as one of the star attractions at the main entrance.

For this proposed exhibition of American ingenuity, brands like Hershey’s, Whirlpool, Morton Salt, and Miller Brewing signed up to showcase their wares inside the World of Food. Yet even with this impressive laundry list of vendors, construction was underfinanced and the building scrapped a month before the fair opened, according to Bill Young, editor of nywf64.com and coauthor of The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair: Creation and Legacy. Companies already pledged to the World of Food were left scrambling for new homes at other pavilions.

Into the void came the exotic offerings at international pavilions, where vendors hawked affordable meals for big families and young visitors who couldn’t or wouldn’t have dined at the kind of upscale restaurants that dominated the 1939 fair. Because of a dispute with the Bureau of International Expositions (the governing body of official World’s Fairs), many of the more established European countries eschewed a presence in Queens in 1964, opening the door for smaller nations like Lebanon and Sierra Leone to take spots previously held by the United Kingdom or France. Instead of avenues lined with five-star restaurants, an appealingly ad hoc street food–style bazaar took shape.

“Looking back, you realize there was no national fast-food presence at the fair,” says Bill Cotter, Young’s coauthor and a New York native who visited the fair as a teenager more times than he can count. Instead of the run-of-the-mill hamburgers, hot dogs, and snow cones offered at the basic concession stands, he says the more interesting places were the international pavilions, “particularly ones that had a budget-priced accessibility to them.”

Thanks to the combination of low cost—99 cents for a full meal—and big tables at the Chun King pavilion, a considerable number of Middle American fairgoers were given their first extended foray into Chinese food. Just one taste solidified our country’s love affair with those little white foldable boxes. “I had Chinese food before the World’s Fair, but this was my first full experience,” remembers fair enthusiast Gary Holmes, whose immersion at 10 years old led to a lifelong appreciation for Chinese cuisine. Likewise, regular Joes and Janes were discovering just what sushi meant at the Japanese pavilion, filling up at the Thai pavilion buffet, trying tandoori under a temple-inspired ceiling at the Indian pavilion, and sampling their first sips of Sangria at the Spanish pavilion.

Many of the smaller international restaurants hedged their bets by putting American dishes alongside the national specialties. At the Moroccan café, a sign advertised hamburgers for 50 cents or shish kebabs and kofte steak for $1. The Jordan pavilion offered a Sudanese hamburger with tahini sauce. Adventurous palates often won out over the burger tedium.

But far and away the biggest international sensation of the fair was something that today’s food truck fans are intimately familiar with: the Belgian, or “Bel-Gem,” as it was called, waffle. The waffles were such a hit that other pavilions started cashing in on the trend—regardless of the fact they were Belgium’s geographic and culinary antithesis. “Even at the Lebanese restaurant, one of the things listed next to the falafel were Belgian waffles,” Cotter says. “It was a tidal wave, and everybody had to have a waffle stand by 1965.”

As for the many vendors originally slated for the World of Food building, Young supposes its last-minute demolition left them without time or resources to secure spots elsewhere. Among the companies absent from the fair following the World of Food’s demise were Miller Brewing, Lipton, and Wise Potato Chips. Apart from brands with their own pavilions, like Coca-Cola and Chunky candy, fairgoers found it hard to find American snack foods beyond the generic concession stands. Instead of its place in the World of Food, Hershey’s was relegated to the massive Better Living Center that funneled its audience along a one-way path past every vendor. “You were trapped, and sometimes I’d say, ‘Oh, forget it, I’m not going through all that to get a Hershey bar,’” Holmes says.

Pinterest

Pinterest