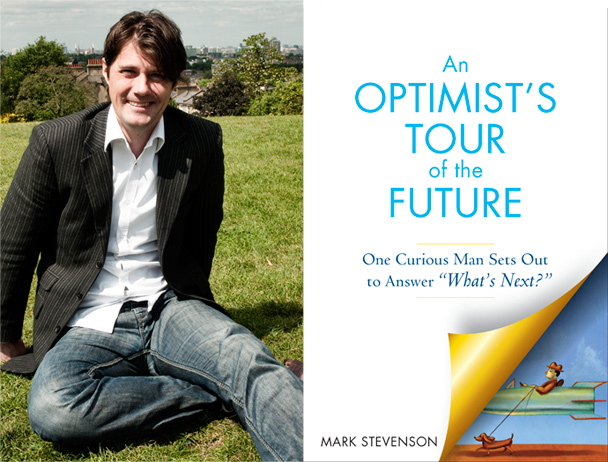

Who’s not a little weary of hearing grim predictions about the future? In search of a fresh perspective, we consulted Mark Stevenson, comedian, consultant, and author of An Optimist’s Tour of the Future: One Curious Man Sets Out to Answer “What’s Next?” (in hardcover now and paperback next month). For the book—which has won praise from The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, and Wired—Stevenson traveled the world talking to farmers, engineers, philosophers, inventors, scientists, and others, who, while not Pollyanna about the future, “see problems and go ‘ooh, goody—now I’ve got something to get my teeth into.’”

Gourmet Live: What made you decide to approach the future from an optimistic viewpoint?

Mark Stevenson: I didn’t. Originally the book was called A World Tour of the Future, but as I did my research, I came to realize that, rather than our future being terrible, it could be a renaissance. I’m not saying the future will be better, but I do believe we still have everything to play for—and everyone of good conscience should be in that game.

GL: Futurists often paint a dire picture when it comes to food, with famine and extinction of various species of plants and animals as two common themes. How would you address their concerns?

MS: With pragmatism. We have the technologies and the knowledge to solve all of our grand challenges right now. I went to the Australian outback to see cattle farms that were increasing their stocking levels, reducing their costs, increasing biodiversity, and pumping carbon from the atmosphere into the soil—all by changing the way the cattle moved between paddocks. Certainly we need to work more in tune with the land rather than trying to make up for our abuse of it with ever more chemical fixes. Also, we need to bear in mind that we haven’t had a shortage of food production; there are more than enough calories per person being made each year. Our crimes are ones of distribution and needless waste, but these can be addressed—that’s not me saying it’s easy.

Species extinction could be reversed, in some cases, if we can rescue—or re-create—the DNA using synthetic biology techniques, but much of what we have lost we have lost forever. The good news for biodiversity is that as human beings increasingly live in cities, natural ecosystems can recover. It’s a little-known fact that Europe is reforesting, for instance—a combination of afforestation policies and natural expansion of forests, mainly onto former agricultural land. That’s not to say we can stop worrying about our forests. We’re still deforesting if you take the world as a whole, but the rate is slowing and its reversal in some areas is encouraging.

GL: In the preface to your book, you have two quotes: “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known,” from Carl Sagan, and “The future is here. It’s just not widely distributed yet,” from William Gibson. How can these ideas be applied to what we eat and drink?

MS: Well, Carl Sagan could have been talking about a new restaurant or dish he hadn’t tried. More seriously, I interpret William Gibson’s point—in part—as saying that ways of thinking and technologies to solve many of our grand challenges already exist, but they take time to propagate. The Holistic Management method of farming I saw in Australia is an example, but that’s only gaining traction now after several decades of dealing with some resistance from the prevailing orthodoxy—a hazard for every idea. So, the solution to your problem might already be waiting for you, but you may need to let go of some old ways of thinking to embrace it. I certainly found a bunch of those solutions on my travels, but I had to let go of some personal biases I’d become comfortable with to appreciate them.

GL: Based on your research, what do you think an average day of eating will look like for Americans in 200 years?

MS: I don’t make predictions. They’d tell you far more about my prejudices than what will actually happen—and that’s the case with many so-called futurists. My work is about saying we have choices, we need to engage with those choices pragmatically, and in that way we’ll get more of the good and less of the bad. I’m not saying it’s all going to be good—I’ve read my history. America has more things to worry about than its future dinner plate. It may not exist in 200 years in its current form if it doesn’t sort out its fossil fuel addiction, Industrial Age education system, and dysfunctional politics—although that’s the same for a lot of countries!

GL: On your “optimist’s tour” of the world, what were your favorites among the foods you sampled?

MS: I spent some time in the Maldives, where the food was a lovely fusion of Asian influences. Also, Stuart Witt, the CEO and general manager of the Mojave Air and Spaceport, gave me a rather nice elk burger (he’s a keen hunter).

Pinterest

Pinterest