In 30 years in New York City, I have shared a table with more cockroaches than I can count. Only once, though, has a frog ever come to dinner. It arrived with our friend Mark W. Moffett, Ph.D., aka Dr. Bugs, who was fresh off an appearance on The Colbert Report promoting his children’s book, Face to Face with Frogs, and it sat out the meal on a banquette at Toloache in the Theater District—a restaurant known for its authentic Mexican cuisine, including Oaxacan-style grasshopper tacos.

But what the frog wrangler and the other seven of us at the table ate that night was anything but entomological. Moffett and his wife Melissa Wells (Lady Bugs, as he calls her) try never to order insects anywhere bugs are not normally part of the cuisine. In Cambodia or New Guinea or Venezuela, sure. At the Explorers Club’s annual orgy featuring the likes of scorpions, maggots, and worms in New York, not so much. “It would be like eating Chinese food in Ohio,” Moffett says.

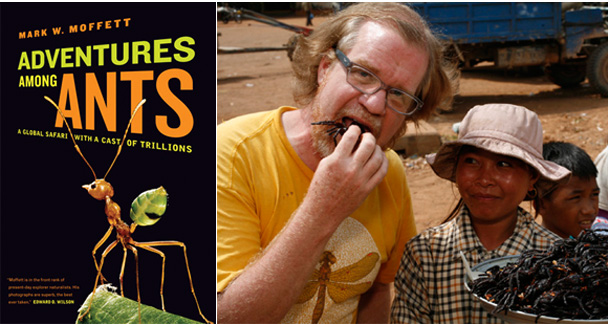

Dr. Bugs, who earned his doctorate in organismic and evolutionary biology under E.O. Wilson at Harvard, has devoted his life to exploring the natural world, primarily studying and photographing insects, including for his latest book, Adventures Among Ants: A Global Safari with a Cast of Trillions. National Geographic has called him the “Indiana Jones of entomology.” He has discovered new species of ants and, he says, “I’ve had a ground beetle from Peru, a rocket frog from Venezuela, and a big-headed ant from French Guiana named after me, as well as a fictional aphrodisiac phallic plant in Amy Tan’s book Saving Fish From Drowning, where I am also a character who grows pot.”

Not surprisingly, his travels have given him endless opportunities to taste extreme cuisine, starting with the guinea pig he faced down on his first trip to South America while in college, back when this kid accustomed to pizza and hot dogs thought a fresh mushroom was exotic. He has been to every country in both Latin America and tropical Asia, plus 30 in Africa, but none in Europe: “Places where they eat normal food I’m apparently not allowed to go.”

In France he certainly would not be dining on one delicacy that he has had in South America but experienced most memorably in Gabon, where he was on a French expedition that dropped the explorers on top of the rain forest canopy by dirigible. The tour leaders had been keeping the explorers nourished with “pâtés and aperitifs, the full French thing going for all meals,” Moffett explains. “We started wondering what Gabon was actually like and on the way out instructed the driver to stop at an actual restaurant where people eat. It was a dirt floor, 15-watt lightbulb, and the menu was all forest meats: pangolin [a scaled anteater that balls up like an armadillo], porcupine, antelope, various kinds of things. One in our group was a vegetarian and was panicking, but she got a vegetarian platter and was really loving that vegetarian platter. She passed it around and I noticed very little brown flecks. Apparently they didn’t grasp the vegetarian idea and had added bits of rat. She not only ate rat but liked it.” He adds, referring to the moment she realized what she’d eaten, “I’ve never seen such a face.…”

Moffett has also eaten one of the world’s largest tarantulas, the Goliath bird-eating spider, which is the size of a dinner plate. And that he had to hunt himself in Venezuela, wearing a tarantula mask to get close enough with a stick to snare it from its burrow, then bringing it back to roast on a fire, which also burns off its poisonous hairs. “Once you’re eating it, you would think it’s crab.”

He will not touch tofu (“needs flavor”) but has had witchetty grubs in Australia and mopane worms in South Africa. (“If they’re not fresh they’re a waste of time. If they’re fresh there’s some butteriness to them.”) In New Guinea he ate palm grubs, raw. (“They’re a big explosion of buttery blubberiness.”) And he ate spiders there called nephila that are so big they can catch birds.

“I once ate a whole wasp colony,” he says. “It was vinegary and crunchy.” Interestingly, texture generally trumps taste with insects because of their exoskeletons. Crunchy is the adjective used most often. Says Moffett, “It never tastes like chicken when it comes to bugs.”

Maybe the tamest things Moffett has put in his mouth are ants, which are used as a spice in many places, including northern India, Venezuela, and Southeast Asia. “Often the toxins associated with their stingers are acids that taste citrusy and pungent,” Moffett explains. “In Venezuela, in any small village restaurant, the hot sauce is made with ants—the heads of leaf-cutter ants.”

“Some villages are famous for their ant colonies. You go to Bordeaux to get the right wine. In Cambodia a single village is famous for its ant larvae. It’s the Bordeaux of ant larvae.” He adds, “The best chicken I ever had was in Cambodia, with ant tapenade: garlic, fish paste, ants. Ants were part of the zest, very punchy.”

Not surprisingly, Moffett is on board with the idea of insects as a food source for a planet that cannot depend on beef forever, which was the subject of a recent article in The New Yorker by Dana Goodyear. Moffett was part of a 1995 conference in China on biodiversity for survival in the future where he learned Mexico and Thailand are the countries that eat the largest variety of bugs, tied at 90 types. “The really nice thing about insects is that they’re good for small-scale agriculture—a village can raise worms and sell them, while owning cattle is expensive and risky.”

Pinterest

Pinterest