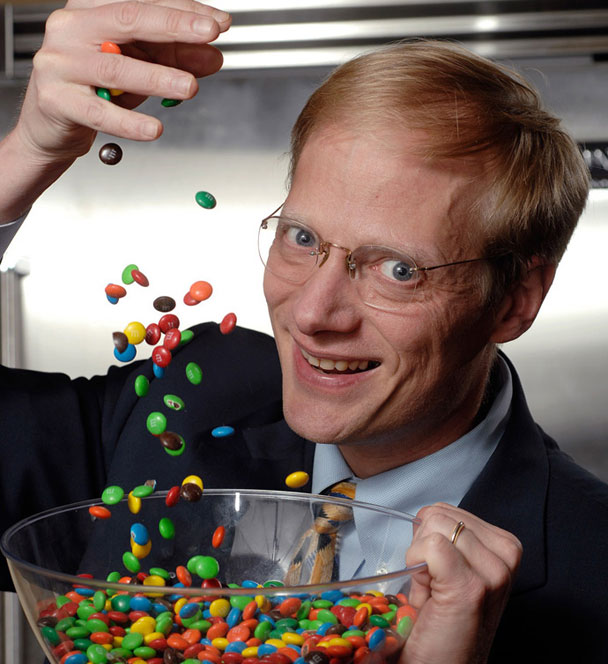

He’s been called the Sherlock Holmes of food, having conducted more than 600 experiments focused on eating behaviors and the psychology of consumption. And for Brian Wansink, Ph.D., it’s a question of learning not only what people are eating but how much. As a professor of consumer behavior at the Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University, and author of Mindless Eating, Dr. Wansink has devoted his entire career to researching how environment influences our eating habits. He weighed in with his most surprising finds, kid–friendly tricks for balanced meals, and what influence the USDA’s recent switch from a food pyramid to a plate has on our diet.

Gourmet Live: What’s the single most powerful change people can make in their lives that would have the greatest impact on improving their health?

Brian Wansink: Identify one major problem that is most vexing for you. Is it meal stuffing, snack grazing, restaurant indulging, party bingeing, desktop or dashboard dining? We all identify with them, but there’s really only one that is the most problematic. Then, find one or two things you can do for one month —just 30 days—that will help you mindlessly tackle that problem.

GL: Of all the experiments you’ve done, which one surprised you the most with its outcome and why?

BW: What shocks me is that I’ve done maybe 600 experiments, and in every single one of these situations where someone is influenced [to overeat], they insist that they weren’t. They might acknowledge that someone else is influenced, but “No, no,” they say. “That would never happen to me.” The total unwillingness of people to even entertain that they could be influenced by anything other than their iron will and their impeccable reason is what is repeatedly stunning to me. And [food professionals] end up being the worst. They are as inaccurate as the person on the street. It’s a wacky, fun world.

GL: Which experiment required the most work?

BW: We wanted to find out if people eat with their eyes or with their stomachs. So first, we asked 150 Parisians how they know when they’re through eating dinner, and the Parisians said, “When we are no longer hungry.” Then we asked 150 Chicagoans the same question, and they said that they know they are full when the plate or bowl they are eating from is empty. So we decided to develop a bottomless soup bowl. And building it was very difficult because you had to have it designed so that the bowl would refill very slowly. As they ate, the level would drop slowly, and when they stopped eating, the bowl would start to fill up again. From a chemical engineering standpoint, it was probably the most technically complex experiment because it had to be realistic.

The outcome of the experiment was really interesting. The typical person who ate from the refillable bowl ate 73 percent more calories of soup, but they didn’t rate themselves as any more full than the person who ended up eating a lot less than a normal bowl. In their mind, they’d eaten a half bowl of soup, so how could they be full?

GL: When you are doing an experiment in a restaurant, and different tables are getting differing treatments with food, drinks, or service, how do you keep the participants from realizing it?

BW: We use something used in magic called “misdirection.” For instance, for a test about wine [in which participants were all given the same wine, but half were given a bottle with the label of a California winery and the other half a bottle with a North Dakota winery label], we tell the participants, “After dinner tonight, we’re going to ask you about your server. We’re training servers so we’re going to ask you about what you think of the server.” Actually, we couldn’t care less about the server, but we kept repeating the word server so they think the experiment is about the server.

GL: What changes have you and your wife made to encourage healthy eating among your three children? Has it worked?

BW: We did research that if you give one group of mothers carrot juice to drink every day during their last trimester, and you give another group water, when you give the baby carrot–flavored cereal, the babies whose mothers had carrot juice in vitro eat more than the babies whose mothers had just water. So the one thing we made sure we did was eat as wide a range of foods as possible, even ones my wife didn’t like. It worked out really well.

GL: What tricks do you use to maintain healthy eating habits while traveling?

BW: I always make sure that I have hot protein for breakfast. If you start off with a hot protein, you’re not going to fall into the crazy habits. The second thing is to drink glasses of water. When we get dehydrated, we confuse our lack of hydration for hunger. We know something’s wrong in our body, but we don’t know what it is. We know we need something, so we think we need food. But more often than not, we need water.

GL: The information you learn from your studies is useful for consumers as well as food companies eager to increase sales. Have any conflicts ever arisen over this?

BW: I’ve found that even companies that you might not think are healthy want help in figuring out how to sell something that’s healthier. I recently helped McDonald’s with their new Happy Meal. We did some research a while back that showed that a child slows down or stops eating a Happy Meal the second they open the toy, and that the majority of the French fries in a Happy Meal weren’t eaten by the child but by the parent they were with. So we reasoned that if McDonald’s dropped the number of calories they give a child in French fries from about 240 to about 100, no child would complain, and their mom or dad wouldn’t get fat. Then, by adding a quarter of the serving of apples to replace those lost fries they could keep the price of the Happy Meal the same.

Pinterest

Pinterest