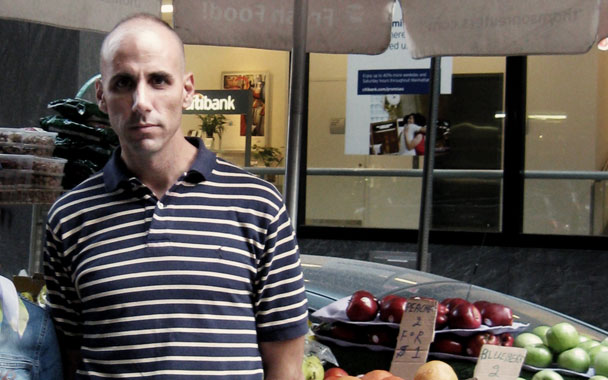

Lawyer and former street-food vendor Sean Basinski is the founder and project director of the Street Vendor Project, a member-based advocacy group for street vendors’ rights at New York City’s Urban Justice Center. For gourmet.com’s Street-Food Week he spoke with research chief Marisa Robertson-Textor about the challenges facing vendors in the Big Apple; his recent research trip to Lagos, Nigeria; and the fantastic success of the Vendy Awards.

Marisa Robertson-Textor: You founded the Street Vendor Project exactly eight years ago, just after September 11, 2001. How has the organization changed since then?

SB: We’re now at about 900 dues-paying members, but our activities remain much the same. A certain amount of our focus goes to defending vendors in lawsuits, getting cases dismissed, recovering confiscated property, etc. The rest is spent on networking, advocacy, and negotiation. Here’s a typical scenario: Today I received a phone call from vendors outside a hospital in Brooklyn. For the past week, local police have been telling them they can’t set up shop—no one knows why, but if they do, they’ll face arrest. And in the meantime, they’re not earning any money. So we’re going to head out there shortly to talk to the police.

MRT: Do vendors here in New York City face particular challenges they wouldn’t elsewhere?

SB: Because many city streets are legally closed to vendors, people here are struggling for a fairly small piece of valuable public space. You or I might think there’s plenty of room on some of these closed streets for a few food carts, but they’ve been deemed too crowded. And then there’s the question of fines. Back in 2004 the city raised the maximum street-vendor fine from $250 to $1,000.

MRT: $1,000 is a hefty fine.

SB: Yes, and that’s for infractions like not displaying your license prominently or not being parked the requisite ten feet from the crosswalk. We sued the city for raising the fine without first holding hearings on the matter that were open to vendors. We had 150 vendors testify, and we ultimately won the case, which put about $2 million back into vendors’ pockets. But in 2006 the city re-raised the fine to $1,000, so it was a short-term victory. Our basic goal is to encourage constructive change, and that remains a real challenge. Also, these sorts of laws have a hugely negative impact on the street-food culture. Portland, Oregon has over two times as many street-food vendors per capita as New York City, and they’re doing it better out there in large part because there’s less bureaucracy.

And speaking of bureaucracy, perhaps the biggest problem involves the laws governing the issuing of new permits. There are a few exceptions in the form of summer permits and “green” permits for fruit and vegetable peddlers, but for all intents and purposes, the cap on new, year-round, city-wide permits is 3,000 a year. So procuring one is difficult, and it leads to all kinds of maneuvering. Let’s say I have a permit, but I don’t need it anymore—I’m a nice guy, I’ll “rent” you the use of my permit for, say, $8,000. You can either pay me that money, or you can wait 15 years—ten if you’re lucky—to get one legally. What would you do?

MRT: Hmm. That would depend in part on how much I could expect to earn once I had the permit. What’s the income of your average street-food vendor?

SB: Almost every vendor I know would be happy to net $100 a day—$140 on a good day. That works out to about $20,000 a year, less if you take a month or two off in winter and visit your family in your home country. So the guys selling fruit, roasted nuts, hot dogs? They’re not making a lot of money.

MRT: Professor Irene Tinker, who’s spent decades studying street food around the world, reports that, the world over, people enter this business to make a living and support their families. As soon as they’ve made a reasonable profit, they move on to something else. Is this true in New York too?

SB: Absolutely. We lose a lot of our best guys to yellow cabs. And that’s quite a statement on how undesirable it must be to be a street vendor, because it’s not heaven to be a taxi driver in New York City. Also keep in mind that these people aren’t entrepreneurs, if by that you mean someone who’s infected by new ideas and wants to transmit them to others. These are workers. Most of the guys selling hot dogs probably don’t even eat hot dogs—they’re eating their wives’ rice and curry lunch. Why not sell that instead? Well, they’re not foodies—they’re not reading Gourmet, they’re not checking out food blogs. Their lives consist of the garages where they keep their carts, the streets where they work, their apartments in the Bronx. It’s not necessarily so easy for them to think outside the box.

MRT: What about the new, “boutique” street-food vendors—how are they doing?

SB: I suspect that for a lot of them, working in street food is a branding opportunity, one step on the path to opening a restaurant or expanding a catering business. But I doubt they’re earning all that much money either. That said, they’re bringing a certain trendiness to the field, and that’s invaluable, because it’s raising the profile of the community as a whole.

MRT: Speaking of trendiness, you’re the brains behind the annual Vendy Awards, which are given to the best street-food vendors in the city. The Vendys have certainly had an enormous impact on the hipness quotient of street food.

SB: We held the first Vendys in 2005, and I think we threw the whole thing together in about three weeks. Now, we’re working a year in advance. We just set next year’s date—September 25, 2010—in part to secure Bobby Flay’s attendance. Bobby Flay! We’ve created a street-food monster. Did you know that owners of Calexico, last year’s Vendy winner, were first inspired to get into the business when they attended the inaugural Vendy Awards? That’s incredible.

MRT: Let’s talk for a minute about the Vendor Power pamphlet, another project of yours. How did that come about?

SB: There’s a great organization called the Center for Urban Pedagogy that pairs advocacy groups with designers, and we worked with them on the pamphlet. Prior to that, the only information available on becoming a vendor was provided by the city, and it was a quarter-inch-thick manual written in undecipherable legalese. Ideally, we’d like every vendor to have a copy of Vendor Power. But the pamphlet is also for the general public, to tell them more about street food and encourage them to value it more highly. Not to mention, the manual is beautiful.

MRT: Beauty and brains! The pamphlet also contains a fascinating statistic on ethnicity: A hundred years ago the vast majority of street vendors in New York City were Jewish—which makes sense given that the Lower East Side was at the time the most densely populated place in the world—while today, 18 percent are Bangladeshi. And as Irene Tinker tells us, in Bangladesh the vast majority of street-food vendors are men, while in Nigeria, where you’ve spent time, street food is a female trade.

SB: What I found in Lagos is that street vending in general is divided about fifty-fifty, which isn’t surprising given that about 70 percent of the local economy takes place in the informal sector. But yes, if you’re talking about home-cooked street food, in Lagos it’s sold almost exclusively by women. Go to the South Bronx, though, and you’ll find it’s women peddling the street food. Is that because in Mexico it’s mostly women who sell street food? I’m not sure. And for that matter, why is almost every guy selling coffee and bagels throughout the city Afghan?

MRT: Back to Lagos: How did you end up there, and how does the street-food scene there compare to New York?

SB: After seven years with The Street Vendor Project, I wanted to take a sabbatical and broaden my horizons. I received a Fulbright to spend half a year in Lagos, a city of 15 million people where the street-vendor culture is far richer than it is here, not by design but by necessity. And the timing ended up being really bad—or maybe really good, depending on your perspective—because two weeks before I arrived, the Lagos state government issued an enormous crackdown on vendors and razed the Oshodi market, which had contained between 20,000 and 30,000 stalls. So there was a lot to talk about, and I ended up writing a report for the local CLEEN Foundation.

But what’s interesting is that the Nigerians I met couldn’t understand why on earth I was studying street food. In their wildest dreams, it had never occurred to them that Americans even eat street food—they think we all shop at supermarkets. And they want to mimic us by doing the same thing. But the irony is that over here we’re trying to mimic them by returning from the unsustainable supermarket model to local food, including street food. So we’re chasing each other.

MRT: That’s another point Irene Tinker touched upon: the inherent unsustainability of the supermarket, with all its hidden costs, versus the sustainability of, and general need for, street food.

SB: Right now in New York City you’re seeing a lot of supermarkets closing due to high rents—they can’t meet their overhead. Yet last week the City Planning Commission approved a proposal to offer tax incentives for the development of new full-service supermarkets. Here’s my question: Why not take that same money and use it to support local fruit and vegetable vendors instead? They’re too small to take business away from the supermarkets, but they can prop up a table, work for a few months, make some money, support their families. Our priorities are in the wrong place.