The first thing I did in the morning—I do this every morning—is make a pot of tea. Black tea. Irish tea. Barry’s Red. My wife, Dona, and I go through two pots in the morning. Piping-hot tea with goat milk, unpasteurized, delicious. I’m still drinking tea while I get the pail and cans ready for milking, while I’m putting on boots. That’s pot number one.

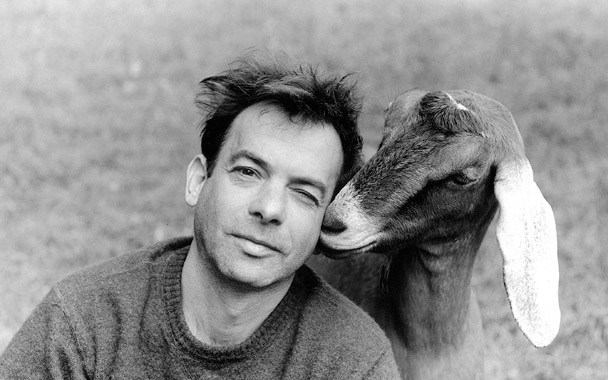

We milk the goats only seasonally, between May and October, so we can all have a break in winter. We’ve been doing this and making cheese for five years. We have nine goats now and a bunch of kids just born in May. I don’t eat anything until after milking. This morning, I toasted a few slices of pecan raisin bread and slathered it with fresh chèvre we made two days ago. My brother is a baker in West Virginia, and he routinely sends these enormous boxes of artisanal bread. So the bread was his, and the chèvre ours. The chèvre was unpasteurized and tasted like nothing you could ever buy in a store—it’s lighter, fresher, more creamy, and it actually tastes like something. It’s the reason we decided to raise goats in the first place. That, and a curious attraction to the animal itself and all the ancient mythology surrounding it: Pan, satyrs, Amalthea, et cetera. But once you’ve eaten a fresh, raw, farmstead chèvre, there’s no going back. You become a junkie. We became junkies. The problem is, you can’t buy or sell this type of cheese anywhere in North America. When we make chèvre—which we do usually twice a week—it’s less like making cheese than making moonshine.

Did I mention that breakfast was washed down with another pot of tea? That’s pot number two.

Lunch was the last stalks of asparagus from the garden and small venison steaks my neighbor Jean brought us. We trade cheese for her fresh eggs, but sometimes she brings us something else from the valley. I marinated the venison in homemade buttermilk—goat milk soured with a squeeze of lime—and let it sit in the fridge for a few hours. Fired up the grill. Coated the asparagus with olive oil, a sprinkle of salt. Grilled the venison, the asparagus, a few slices of pain au levain. Ran to the garden. Pulled a head of young garlic, stripped its green, and threw that on the grill too.

Just as I put everything on the table, one of the goat kids started screaming bloody murder outside. He had gotten out of the new fencing (they always find the weak link) and was screaming because he was separated from the others. Dona dropped him back over the fence and came inside. She’s a vegetarian and usually doesn’t eat lunch, but today she prepared a salad of baby lettuce and arugula from the garden, and took half a wheel of a tomme from the fridge. The tomme is the only cheese we can sell, because it’s aged for more than two months; a raw milk cheese can be sold in the U.S. only if it’s been aged that long. We make enough tomme for ourselves and we trade some locally, and occasionally we sell a few wheels to restaurants. Dona’s lunch was a nice wedge of tomme with the grilled bread and asparagus and the salad from the garden. My venison was red in the middle and surprisingly tender (I was able to cut it with a butter knife). I grabbed a cake of chèvre from the fridge—this one rolled in summer savory—and put a little on the grilled bread. Why not? We shared another pot of tea. That was number four or five for the day. I lost track.

Dinner was late, after the evening milking. We had fresh ricotta in the fridge that I made the night before after making tomme. You can make the most delicious, silken ricotta from fresh whey that comes from making tomme (or any hard cheese) but it takes a bit of time, and the yield is so meager, I usually don’t bother. From the ten gallons of whey, I made a ball of ricotta the size of a cantaloupe.

So the question was, what to do with the ricotta? We weren’t feeling very ambitious by then. I thought we could just eat it with fresh strawberries, but we had no fresh strawberries (they’re about a week away). Instead, I made ricotta fritters with Swiss chard from the garden. The ricotta, the chard, an egg, and breadcrumbs, a little flour. We ate that with a lightly dressed salad and garden radishes. A bottle of Michele Chiarlo Barbera d’Asti. So that was dinner. What else? There were pickles that we’d put up last year. Dill pickles from the garden for me; Dona ate bread-and-butter ones.

Dessert was peaches and—yes—a slice or two of tomme. Before we raised goats I never ate a lot of cheese. I was a bit intolerant of pasteurized cow milk, and the cheeses made from it, but our goat milk I have no problem with. We know everything that goes into our cheese, our labor and each doe’s labor, and what she’s been eating in the pasture and woods—the clover and wild bergamot, the birch and beech and ash leaves—and so ingesting it is a very intimate, almost familial experience. Now that we make our own, cheese constitutes a large part of our diet. We eat tomme throughout the year, and we freeze the chèvre curd and bring it out in winter. We also make a fresh mozzarella.

Most everything on the table that day—the tomme, the ricotta, the chard, the pickles, the eggs, asparagus, the venison—came from our valley. All except the peaches. The damn peaches. They came from Georgia. And, of course, the wine and olive oil. That would be Italy. Piedmont, Umbria. Alas, some things we just can’t grow in our backyard.

Pinterest

Pinterest