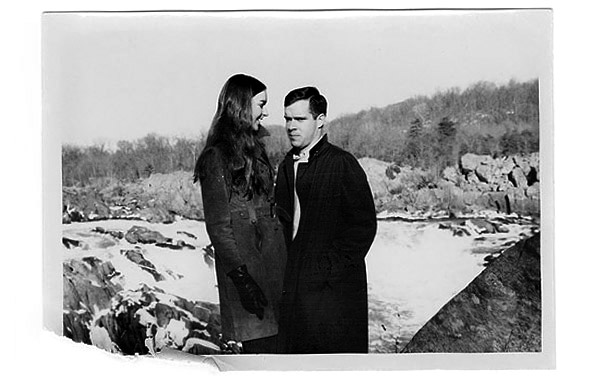

It was 1970. Stevie Wonder’s “Signed, Sealed, Delivered, I’m Yours” topped the R&B charts. Women wore their hair long, straight, and shiny. Gail Kennedy was 21 and had just married 22-year-old Jim Van Buren. She was pregnant in this photo, though she didn’t know it yet. He would leave for Vietnam in a few months, and would not meet his first daughter—my older sister—until she was six months old.

Every year around St. Patrick’s Day, certain Irish food stereotypes are resurrected: the endless potatoes, the corned beef and boiled-to-death cabbage (a dish that’s rarely eaten in Ireland, overcooked or not). But the Irish culinary experience is far richer and more varied, reaching far beyond this single day to hundreds of ordinary days and ordinary meals. Recently, as I thought about the foods that my Irish-American mother makes for St. Patrick’s Day (and their possible relationship to my own bizarrely enduring hatred of cabbage), I started to wonder about the everyday dinners in her life. This is her story—the story of a girl who grew up poor in a family of nine in 1960s Long Island, and of a woman who fell in love, moved to Boston, and supported her family on a waitress’s salary.

My parents attended neighboring Catholic high schools and first met on a double date. Mom had sewn an empire-waist dress out of one of her mother’s old skirts. It was covered with a green turtle print. Dad was struck by her long, dark hair and Irish looks—though he is of mixed Irish descent himself, “She didn’t look like anyone else I knew.”

Soon Dad was going to Mom’s house for dinner. Her three sisters would stand on the front staircase and sing the popular tune “Jimmy’s Back,” with synchronized dance moves, to greet him. Mom’s father, a first-generation Irishman, worked a low-paying job as a buyer at JCPenney; Granny, also first-generation, would stretch a pound of meat to make meatball-sized burgers for dinner. There would always be potatoes on the side, and the kids filled up on bread and jam afterwards. The first time my six-foot-tall father ate with the Kennedys, he took one look at the scant supply and knew this wouldn’t be a filling meal. He let his stomach grumble that evening; from that point forward, anytime he went there for dinner, he made sure to eat at home beforehand. He was one of eight kids, but his father was a doctor, and their burgers were the size of hockey pucks.

On Fridays, both families ate fish. At Mom’s house that meant a couple cans of tuna, hard-boiled eggs, lettuce, and tomato. At Dad’s it was tuna sandwiches or fish sticks. Granny would occasionally splurge on fresh sole as a treat, but Mom vividly recalls her first taste of a fresh clam while visiting a wealthy friend in the Hamptons: “It was like putting on glasses for the first time.”

My parents married in a ceremony full of polyester, with purple flower-print bridesmaid’s dresses. Mom lived with her parents while Dad went overseas with the Marines. Thirteen months later, he returned to scoop up wife and baby and move to Boston, where he had enrolled in law school at Boston University. The G.I. Bill paid tuition, and Dad got paid internships during the summers, but they still needed rent money—so Mom took a waitress job at the original branch of Legal Sea Foods.

The staff was a florid group of Irishwomen twice her age. They perched my sister at the bar to drink ginger ale and eat crackers while they washed down the tables and floor with piping-hot coffee, a tradition that one coworker imposed on the group. The staff meal consisted of odds and ends—bits of fish, or a few dozen potatoes. After everyone had their fill, waitresses packed fish scraps for their cats. Eventually word got out that Mom didn’t have a cat—just a baby and a husband. “After that got out,” says my father, “the number of shrimp and scallops in her portion went up exponentially.” (My mother laughs: “We never saw shrimp or scallops,” she says. “Maybe once or twice—your father has a way of elaborating.”)

With her Irish background, my second-generation mother almost fit in at work—until one St. Patrick’s Day, when she brought in Irish soda bread that she’d made using a traditional recipe. No one would touch it.

“I finally said, ‘What’s wrong with it?’” she recalls, still bristling at the memory.

Her coworker pointed out, in a thick brogue, that she had failed to press the sign of the cross into the top before cooking it. It was sacrilegious. No real Irishwoman would touch it. “I always just thought that was an ‘X,’” Mom explains glumly. “And that was a good soda bread recipe!”

Mom waitressed at Legal until she was nine months pregnant with me. Men jumped out of their chairs as she approached their tables balancing plates on her belly: “My tips were pretty great that year,” she remembers. After I was born and Dad had finished school, they moved to a small suburb west of the city. My father started his own legal practice. A third baby—my brother—arrived. My parents continued to scrimp and save, moving to an old fixer-upper Colonial followed by an unattractive rental split-level house in Worcester.

Now, at last, they have their dream home, a modest house by the water painted in the colors of the sea. Dad grills burgers in whatever size he wants, and Mom’s favorite food to cook is still fish. She makes the famous Legal chowder, so good that Dad brags about it to anyone who will listen. Its beauty, she has taught me, is simple: really good cream, butter, white fish, white pepper, and white onion. She cooks, and he does the dishes.

Walking home one night to my rent-stabilized studio in Brooklyn, I listen to Stevie Wonder on my iPod and ponder what I have in common with my mother. I am 32. She is 59. My navy dress is from a clothing swap. The vintage coat is “inherited” from a friend. I splurged on the pretty yellow bag, sure, and the one pair of good boots. There might be a hole in these stockings, but it’s hidden. They still work to keep out the cold.

My frugality comes from a different place than hers did: I am neither a mother nor an immigrant, but a freelance writer cautious in a new economy. And about love, I have nothing to add. Like many single women, I am nearly inarticulate about what I think I’m looking for.

I trot up the steps of my walkup, swing open my door, and sit at my laptop. A photo blazes through the ether. Another ’70s snapshot. They are both smiling. Her eyes are almost crinkled shut with happiness. He gazes at her and looks—there is no other word for it—incredulous at his good fortune: Signed, sealed, delivered, I’m yours.

Pinterest

Pinterest