I’m becoming my mother. It’s a realization I have often, but it was on a family vacation this summer that I saw the change in every aspect of my life. Even food. I thought my mom and I had grown apart, or never really been alike, in this regard: my mom loves a bargain; I just love good food. Don’t get me wrong, she loves good food too (she once conceded that Nobu’s lobster tempura was “almost worth it”), but she gets the greatest thrill when she finds a “good deal” on culinary luxuries. (So, surf and turf for $20 is a good deal; mixed green salad for $8 is not.)

For my mom, a chemist-turned-business-executive, the calculations come naturally. So too does the perceived value of meat and seafood, all rarities for her during her childhood in post-war Hong Kong and her days as a poor international student at Berkeley. It was her frugality during her pursuit of the American dream that gave our family the means and freedom to eat well.

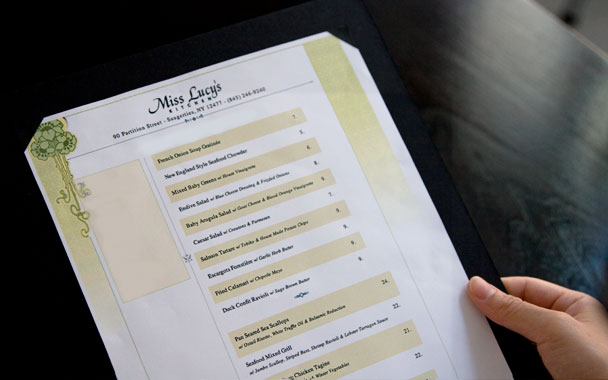

Knowing this, I carefully chose the restaurant for our final vacation dinner in Saugerties, a quaint New York town. I settled on Miss Lucy’s Kitchen, an upscale but fairly priced place that features ingredients from local farms. Once seated, my mom studied the menu, making her decision out loud.

“What’s a hanger steak?” Her tone teetered between skeptical and hopeful. “Is it like filet mignon?”

In other words, is it worthy of its listed price? Should I tell her that hanger steak is a cheap butcher cut, but, because it’s trendy, restaurants sell it for the same price as filet mignon?

“It’s very flavorful, Mom, even meatier than filet mignon. A little more like flank steak.”

She wasn’t buying it and moved on down the menu. I tried to ignore her mumblings: “I wonder how many pieces of lobster come with the pasta? Why does their duck entrée only include the breast?”

While I tuned out her chatter, I couldn’t ignore the voice in my own head: “That pasta sounds good, but is it homemade? Ooh, the sea bass comes with fava beans—I wonder how many?” I started weighing whether the appeal of fava beans, a pain to shuck and peel at home, were worth more to me than seared duck breast, which I was craving. For how many fava beans would I trade my real desire?

“This looks good!” my mom said, pointing to the bottom of the menu, “A paella with rabbit and shrimp and sausage and snails.”

“Mmmm, you’re right, Mom. Let’s get it.” The dish sounded both delicious and like something I wouldn’t make at home.

And then it hit me. I was doing the exact same thing my mom was, just based on a different set of gastronomic values. My mom’s calculations, like a mental Excel spreadsheet, ultimately gave her what she wanted, namely a good price for a lot of protein. My fuzzy logic, combined with dreadful mental math skills, favored items I considered priceless, dishes that I couldn’t make at home for lack of time, expertise, or ingredients. Dining out, for us, seemed to be an exercise in measuring what we value against the numbers printed on the menu.

When our entrées arrived, my mom’s eyes widened. The paella, studded with plump snails and bits of rabbit confit, was topped with two jumbo shrimp, a glistening crimson sausage link, and what appeared to be half of a pan-fried rabbit. But it wasn’t just the quantity of food that was impressive. Each component was perfectly cooked and came together into a perfect whole.

After eating as much as she could, my mom waved down the waitress.

“I have a question about the paella.”

I was terrified she was going to ask about its price, whether there was some hidden charge we had to pay for the dish’s opulence, its warm, wild flavors, its rustic charm.

Instead, she asked, “Where’s this sausage from? Do you make it here? The pork tastes really fresh, and the spices too.”

Wait. My mom wanted to know the sausage’s provenance rather than its price? That’s something I would ask. Was my mother becoming me?

The waitress indulged us, “We don’t make the sausages ourselves. They’re from a smokehouse just down the road.”

As she reached down to clear our plates, my mom and I simultaneously said, “Oh, we want to pack that up,” gesturing towards a tiny mound of paella. It’s a compulsion I picked up from my mom—and of which I’ve learned to be proud—I always save any food that’s left.

After we shared a few deeply satisfying desserts, my husband picked up the bill; my mom didn’t even ask to check the math like she always does. Neither did I. We both just thanked him. We were full and fully content, happy to have had such a wonderful meal with our family. And that’s really what both of us value most.