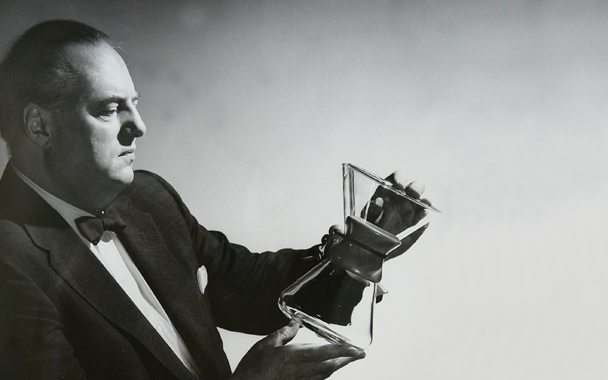

The Chemex coffee maker is part chemist’s funnel, part Erlenmeyer flask, with a blond leather band in the middle corseting its hourglass curves. An iconic symbol of German modernism and simple, functional Bauhaus style, the device—a Pyrex glass container with a sturdy paper filter—produced M.F.K. Fisher’s favorite cup of coffee and still holds an alluring power over coffee purists and design geeks. Its success launched its inventor, Dr. Peter Schlumbohm, into the arms of the design establishment (the coffee maker has been a part of the MOMA’s design collection since 1944, just three years after Schlumbohm patented it), and in the early years of World War II, it was considered a patriotic alternative to products made from metals and plastics (which were essential to the war effort). A Time Magazine article from November 1946 quotes the ebullient inventor as saying, “with the Chemex, even a moron can make good coffee.”

Though the sleek product is now firmly established in the design canon, none of Schlumbohm’s other inventions had the same staying power. But these lost gadgets spoke to his hedonistic lifestyle, and to the particular preoccupations of bachelors in the Mad Men era.

Wait, there’s more. For the man about town lugging a warm bottle of Champagne, the disposable Instant Ice container chilled the bottle in brine (just add water!) down to 44 degrees in less than 20 minutes. And why doesn’t water taste more like Champagne, anyway? The Minnehaha forced water through hundreds of tiny perforations, supposedly improving its flavor through aeration and cooling, and doubling, conveniently, as a cocktail mixer. Cocktail shakers leaked and jammed, but Schlumbohm’s Pyrex shaker apparently did neither. And the oddly named Tubadipdrip was primarily a coffee and tea maker; without surprise, it too pulled double duty as a cocktail mixer.

And for the gourmet stuck in a small apartment, there was the original combi-appliance: electric oven, ice-cream maker, frozen food chest, thermos, dishwasher, and air conditioner, all in one. In Schlumbohm’s world it was known as The Tempot, and Time Magazine predicted in 1946, without a hint of sarcasm, that this invention would “make its way without trouble in the commercial world.” When Time returned in 1949 to report again on the inventor, it found that only 20 Tempots were ever made and that the machine was, sadly, “no longer in production.”

Schlumbohm—more than six feet tall and nearly three hundred pounds, with a booming voice and burly laugh—spent eight years pursuing a doctorate in chemistry at the University of Berlin (after striking a deal with his family to give up all rights to his father’s estate and his inheritance if they would support him through school). The young inventor wrote papers published by the University of Hamburg calling for the abolition of the military (he’d reluctantly served as an artillery captain in World War I), and studied Gestalt psychology under Wolfgang Kohler, one of its founders, who believed (in opposition to prevailing views of the time) that not all problems were solved based on past experiences or trial and error. Schlumbohm’s learning under Kohler would prove essential to his process of discovery.

As would his bachelor lifestyle. “He loved to drink and he loved to eat,” says Roy Doty, a cartoonist who was a friend of the late inventor, “so going out for dinner with Dr. Schlumbohm was a horrifying experience.” Guests were treated to epic all-night food crawls in his huge Cadillac Coupe De Ville, which he pimped out with built-in shades and a solid-gold Chemex coffee maker bolted to the driver’s door. (When he traded in his car every two years, he removed the golden amulet and set it on the newer, larger model.) Like many German immigrants, Schlumbohm felt at home in Manhattan’s Yorkville neighborhood, once a stronghold of German restaurants and coffee shops. He drove his guests up into the 80s, handed anyone loitering near the area a ten-dollar bill to watch the car, and then marched in for his first course. Soon, they all piled back into the car and moved on to the next joint. “Eventually,” says Doty, “you’d be somewhere eating streusel with him and by that time it was two or three in the morning.” But three in the morning was nothing to Schlumbohm, who surrounded himself with fellow night owls and often made calls around that time to discuss his newest ideas.

Pinterest

Pinterest