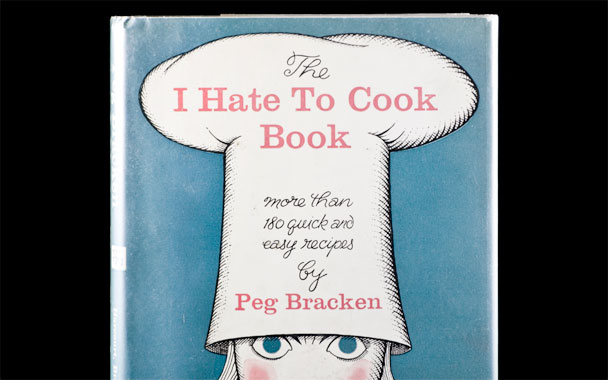

Looking back on 2007, the year we lost both Norman Mailer and Peg Bracken, I can tell you which one of these icons of Americana I’m going to miss, and it won’t be the pugnacious little misogynist who kept his ego fully inflated long past the early death of his talent. I’ll miss Peg. No, I didn’t know her personally, nor was I ever tempted to try one of the recipes in her masterpiece, “The I Hate to Cook Book,” which came out in 1960. By the time I fell in love with the book, it was some 40 years old; and even I, a pathetically gullible reader of cookbooks, no longer believed a teaspoon of curry powder was going to do anything very positive for canned cream-of-chicken soup. That didn’t matter. Food was nowhere near the heart of Peg Bracken’s greatness. It was freedom—a word she might have piped in frosting across a cake-mix cake, if it weren’t such a ridiculous amount of trouble to start writing on cakes.

Bracken’s target was all the emotional baggage that women dragged into the kitchen with them whenever it was time to cook. Back in the 1940s, when she was starting married life, women who cooked badly and were horribly aware of it had guilt snapping at their heels from breakfast to dinner. To fail at cooking was to fail at femininity, not to mention love, motherhood and the honor of the family. Good cooks had an easier time of it, but by midcentury even they weren’t fully immune, because the very definition of good cooking was always moving just out of reach. No sooner had you mastered pot roast and chocolate cake than seafood tetrazzini and madeleines hovered into view. Only the women who cooked as naturally as they breathed, and liked to confess laughingly that they couldn’t follow a recipe if they tried, lived in that blissful realm beyond the icy grip of inadequacy.

But easy recipes alone were not going to banish guilt and self-loathing. By the time Bracken sat down write a cookbook, easy recipes had been abundant for years without making any discernible headway against kitchen guilt. The food industry was churning them out as automatically as it churned out boxes of instant pudding, and helpless cooks had to look no further than the food section in the daily paper to find detailed instructions for opening two cans of soup and mixing them together. What’s more, it was perfectly okay to cook that way. You could serve a Shanghai Salad made from a can of beansprouts and another of water chestnuts without embarrassment; you could pass around slices of bologna folded like little cornucopias over dabs of cream cheese and call them hors d’oeuvres; you could even mix vanilla ice cream with Grape Nuts and pour over it a sauce made from melted caramels and marshmallows—this was entirely permissible by the standards of the time. But crossing the finish line didn’t mean you felt victorious.

Bracken’s easy recipes were a lot like everyone else’s—except for the writing. She perfected the relaxed voice and style of a genial neighbor to whom humor was a way of life, and she absolutely refused to take cooking seriously. That turned out to make all the difference. The food didn’t have to change; your perspective on life and dinner had to change, and she could make the shackles of guilt fall away just by eyeing them with a dry and relentless skepticism. Feeling like a wastrel because you bought a frozen chicken pie or a box of pie-crust mix? Quit beating yourself up about it. “Maybe you do your own wallpapering, while that lady down the block, who so virtuously rolls her own noodles, pays vast sums to paper hangers. Maybe you make your own clothes, or sell Christmas cards at home, or maybe you’re just plain cute to have around the house.” If you’re hesitating to serve some desperate glop of ground beef topped with corn-muffin mix even to your husband, one quick way to improve it is to haul out a bottle of wine. (Note: this was a genuinely radical suggestion. Nobody had wine for family dinner in 1960, except recent immigrants who still knew how to live). “The sort of wine doesn’t matter too much,” Bracken counselled. “It can be a whimsical little $4.95 bottle or a downright comical 59 cent vintage; it’s the principle of the thing that counts.” And, of course, I can’t overlook what is probably the most beloved instruction all American recipe-writing, from her directions for Skid Road Stroganoff: “Add the flour, salt, paprika, and mushrooms, stir, and let it cook five minutes while you light a cigarette and stare sullenly at the sink.”

“The I Hate to Cook Book” sold some three million copies, many of them to people like Bracken, who didn’t mind cooking at all but hated the moral, social and culinary commandments that came raining down like arrows when they started to plan a meal. It’s still worth a place on your cookbook shelf. True, the recipes show their age every time canned potatoes or processed cheese make an appearance. But her sense of humor remains beautifully in tune to this day. What’s more, it’s clear today that an honest food-lover is presiding over this book, someone who insists on a real vinaigrette, a decent loaf of French bread, a dash of brandy in the pumpkin pie, and crystallized ginger just about anywhere it will do some good.

Bracken didn’t start a revolution, either in food or in women’s lives, though for sure she could hear both those revolutions rumbling in the distance. What she did manage to establish was a healthy bit of distance between the cook and the meal, the homemaker and the home, the woman and her assigned lot in life. She used wit as if it were a handy screwdriver, gently prying apart two entities that had been clamped together for centuries; and she created a little breathing room. Okay, Brillat-Savarin was right; we are what we eat. But most assuredly, we are not what we cook. For that welcome lesson in culinary sanity, pour a glass of the best you have and offer a toast to Peg.

Pinterest

Pinterest