My friend Gobbie gave me my copy of the 1957 edition of Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls when I was seven years old, and I still have it. The back cover has come off, the pages are yellowed; yet it has survived not only my childhood, but also my adulthood’s gradual divestment of childhood artifacts through countless moves and annual spring cleanings.

Within the spiral bindings of this book are the origins of my love of cooking. My earliest memories are of Raggedy Ann Salad made from canned peach halves; and Heart Cake, baked in a round and a square cake pan, then spliced together and subsequently adorned with fluffy white frosting and heart-shaped red candy. I made Apple Crisp and Sloppy Joes, and so many Whiz Cinnamon Rolls that the pages for that recipe are now stuck together.

There were a few rip-offs, like the Carrot Curls that didn’t stay curled no matter how long you soaked them in ice water. The Good Kid Cookies were another bust; though they were supposed to look like children’s faces, mine were never much more than blurry blobs.

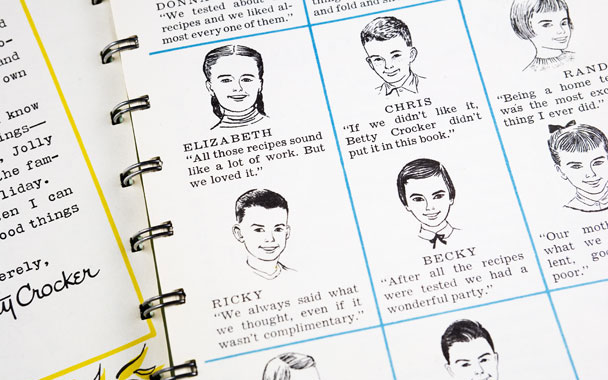

No matter. I tried nearly every recipe in the book. At no point did I question whether I was up to the challenge of making a successful Cheese Dream or Jolly Breakfast Ring, and for this lack of anxiety I credit the panel of 12 children whose headshot illustrations appear in the front of the book: “Meet Our Home Testers,” it says.

They look like prim Eisenhower-era kids, and they have wholesome names to match: Donna, Peter, Lucy, Elizabeth, Chris, Randee, Ricky, Becky, Linda, Bette Anne, Eric, and Eileen. The hairstyles are equally conventional: pageboys and bobs for the girls, Beaver Cleaver cuts for the boys.

If you spent any time at all in the pages of this book, you felt like you knew these children, because their pictures were scattered throughout, each appearance accompanied by a helpful tip. “This makes dreamy fudge,” quips Donna. “Betty Crocker said not to worry about a crack in your nut bread,” says Chris.

According to General Mills, the book was aimed at 8- to 12-year-olds—children old enough to make their way in the kitchen but young enough to enjoy being there. The full flowering of pubescent cynicism was a few years away, which meant that readers were still capable of belief in, if not Santa Claus, a benevolent Mom-ish woman named Betty Crocker and her brood of child testers.

Anyone who regularly used Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls wished he or she could have been one of those 12 children. They knew Betty Crocker! They got to make Funny Bunny Cakes! Their opinions were consulted on whether or not to include the Spanish Rice! As I frosted cakes and assembled casseroles in my mother’s kitchen, my heart yearned for a spot on the Betty Crocker testing panel.

Recently, I started wondering what ever became of those kids that I so admired. And so I went in search of the panel of testers, beginning with General Mills. Pam Becker, manager in the brand public relations department for Betty Crocker, sent me a fax stating that there were indeed actual children who tested the recipes, but that the company archives has no record of their last names or whereabouts.

Then, after much fruitless online browsing for any mention of the kids, I finally found a 2004 Website for a cookie jar exhibit in a museum in tiny Cranbury, New Jersey—population 3,200 when everyone is home for the holidays. The exhibit included Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls and claimed that—well, well, well—the 12 testers were from Cranbury. But my calls to the museum’s posted phone numbers went unreturned, a trail gone cold.

In the meantime, I found the book’s illustrator, Gloria Kamen, who has had a long career as a children’s book illustrator and author. In 1957, she was an expecting mother of one whose fee did not include royalties for her copious illustrations throughout the book, something she regretted as it sold more than a million copies. I could hardly wait to hear the story about her sketching these children from Cranbury, and how they fell under such a bright beam of luck.

“Oh, no,” she told me, “I was hired to illustrate the book after it was finished and in the hands of Simon & Schuster.” She had some photos, she said, but mostly she made up the illustrations by using her daughter and her friends in the neighborhood. If there were indeed 12 children who tested the recipes, she never met a single one. “General Mills is in Minnesota, right?” she said. “So they wouldn’t have been from the East Coast.”

As for Eric and Donna, Linda and Peter, I began to suspect that the children on the testing panel were just like Betty Crocker, a palace lie.

The Cranbury lead—decidedly East Coast—was the only thread still hanging. A final call to the Cranbury Historical and Preservation Society reached a staff member. “Yes, that’s right,” she said, “the children were from Cranbury.” I told her that no one at General Mills knew anything about this, and she said, “Well, they’re all too young.” Then, to my shock, she gave me the testers’ full names and their phone numbers.

In short order, I was speaking with Eric Sonnichsen, the very same Eric who says in the cookbook, “Baking is as much fun as my chemistry set!” It seems that Eric’s mother, Thelma Sonnichsen, was the cookbook’s linchpin. Thelma had worked as a "home economist" at Lever Brothers with Janette Kelley, who went on to develop the first test kitchens at General Mills. The two women had kept in touch, and one day Janette called Thelma about putting together a pamphlet of recipes for children, to be sold with sacks of flour.

Pinterest

Pinterest