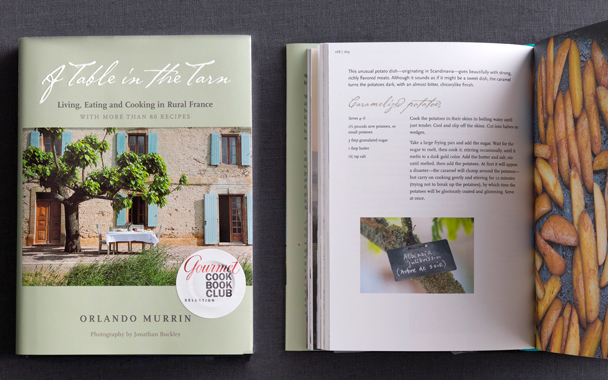

All bed-and-breakfasts are not created equal. Nosy hosts, insipid waffles, bizarre fellow guests, allegedly haunted rooms—we’ve all been there. But then the cover of Orlando Murrin’s handsome book, A Table in the Tarn (a new edition by Stewart, Tabori & Chang; 256 pages; $30), turned my head. There it was: a photograph of a crisp linen-covered teak table set out on the gravel terrace of a blue-shuttered French manor house; a vase of newly cut flowers, a plate of fresh muffins, and a tall jar of homemade granola on the table—the B&B of my dreams. Inside, I found the heartwarming story of two men from London who, back in 2002, mapped out a plan to leave their professional jobs (Murrin, editor of the BBC magazines Good Food and Olive; his partner, Peter Steggall, an IT director in financial services) to open a posh yet minimalist guesthouse—Le Manoir de Raynaudes—in the Tarn département in southwest France, near the Pyrenees. Although they now work 18-hour days (Murrin in the kitchen, garden, and markets; Steggall attending to the guests, wine, cheese course, and accounts), they clearly love every minute of it. Murrin’s very personal stories of the land, his own garden, and the passionate, food-obsessed locals are fascinating; his lovely recipes, rooted in the cuisine of the region, take you to a gastronomic place that will, no doubt, influence your own cooking.

After introducing us to “the cast”—the lucky few who work at the manoir and the villagers of Raynaudes (population 16), who happily share their culinary wisdom with him—Murrin breezily recounts the ups and downs of the planning, house searching, and renovating that went on before the first guests arrived in May 2004. But the true heart of this book lies in the recipes that he has perfected over the years. His savory “le cake”, with its heavenly blend of herbs (we use parsley, dill, and/or chives for brightness), salty pancetta and olives (Kalamatas are ideal), and mild Reblochon, is amazing when served in warm little slices with a glass of wine—or, as Murrin suggests, an aperitif, such as a Kir Royale—and nothing more. (If you make a loaf beforehand—and it really is more like bread than cake—be sure to reheat it, wrapped in foil in a 350-degree oven, for maximum oomph.) This seductive recipe, the first we tried, had us swooning for more. Chapters of hors d’oeuvres, starters, main courses, desserts, and, of course, breakfasts later, we are still swooning.

And for those of us who enjoy cooking tips and secrets, A Table in the Tarn is packed with them. In one recipe, Murrin uses a darning needle (an idea he picked up from neighbor Mme. Bonné) to puncture prunes before marinating them in tea, and then in syrup and Armagnac; in another, he spells out a plating secret for pommes dauphinoise (he bakes the potatoes in a parchment-paper-lined pan, refrigerates them, cuts them when cold into round, square, or rectangular portions, and then reheats them at the last minute—voilà!); in another, he tells you how to make your own baking tiles. Murrin also sets aside pages that serve as mini-lessons. In one, he offers up his stock recipes (naturally, all include a glass of wine), another demystifies making foams, and another—my favorite—lists his trusty kitchen gadgets. (I’m now searching for a necklace-style timer so I, too, can garden while I cook.)

Recently, I hauled out the atlas and found Raynaudes. A girl can dream. Meanwhile, I have the recipes, and now you do, too.

the shape of cakes to come

Modern baking came to be the way all good things (antibiotics, petting zoos, firecrackers) came to be: through trial and error. As techniques improved over the centuries, what was essentially dry porridge evolved into familiar breads, cakes, and pastries. Different cultures tinkered with local ingredients (ancient Egyptians used honey, the Romans added yeast), and the path of baked goods diverged into the savory and the sweet. But some overlap still exists: rice cakes, fruitcakes, and “le cake.”—Chris Dudley

- Selected recipes: (registration required)

- “Le cake” Aux Olives Et Au Reblochon

- Salade Aveyronnaise (Web-exclusive)

- Choco-Walnut Armagnac Fudge (Web-exclusive)