Marriage to Victor Hazan, a New Yorker, meant straddling the Old World and the New. In 1969, Marcella began teaching Italian-cooking classes out of their small apartment kitchen in midtown Manhattan. Her first American students were six ladies she met while taking a course in Chinese cooking. “What do you eat at home?” they wondered, and so Marcella introduced them to lamb kidneys, squid, rabbit, and fish with the head on. After a year, it was time to recruit more students.

Victor recalled having seen a list of cooking schools come out in The New York Times food section toward the end of the summer. “I’ll write to them,” he said, “and perhaps they’ll add your name to the list.” Shortly thereafter, we received a letter from the Times. They were sorry, but the list had already been set and it was too late to include my classes in it. “That’s that!” I said. My new career had been a short one, and I started to look around to see how I could fill my time.

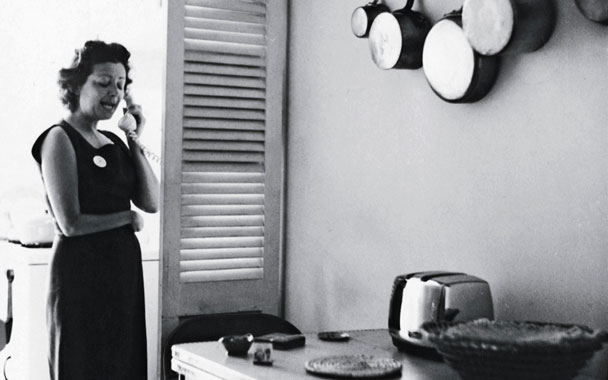

Two or three weeks later, I had a telephone call from a stranger. I was then—and to a degree, I am today—uncomfortable speaking English over the telephone. On the phone, a foreign language sounds even more foreign. It was a man from the Times. He wanted to come over and interview me about my cooking class.

“When would you like to come?” I asked. “How about Wednesday?” he said. “That’s fine,” I said. “What time?”

“Twelve-thirty.”

“Oh, at twelve-thirty my husband and I are having lunch.”

“Well, then, how about Thursday?”

“That’s fine,” I said. “What time?”

“Twelve-thirty.”

“But my husband comes home for lunch every day at twelve-thirty. If you really want to come at that time, come for lunch.”

He said he did not usually accept lunch invitations, but he was intrigued to hear that Victor would be there, and he accepted.

“Anything new this morning?” Victor asked at lunch. I told him about the call from the Times. “Who was it?” he asked. “Someone named Crec, Greg, I didn’t catch the name.” I have never been a good catcher of names. “Could it have been Craig Claiborne?” “That’s it!” I said. “You know who he is,” he said. “Don’t you remember that you always read his columns in the food section of the Times? He is the most famous food writer in America.”

I decided to serve Claiborne a complete Italian meal—appetizer, first course, second course, salad, dessert. For the appetizer, I made carciofi alla romana, artichokes served upside down with their stems pointing up, as I had learned to do in Rome. My first course was one we used to make often at home in Cesenatico, tortelloni di bieta e ricotta, hand-rolled pasta shaped into tortelloni and stuffed with Swiss chard and ricotta. The second course was rollatini di vitello, veal rolls stuffed with pancetta and parmesan cheese, cooked in butter and tomatoes, and sauced with a few drops of their pan juices reduced with white wine. The salad was raw finocchio sliced very thin, seasoned with salt, olive oil, and black pepper. It was too much food to end in a sweet dessert, so I prepared one of my favorite fruit bowls, arance marinate, peeled, sliced oranges marinated with a little bit of sugar and served cold. It was a lovely meal. Nearly 40 years have passed, but I don’t think I can improve on it.

I knew nothing about interviews. To me, it was just a guest joining us for lunch. The food was the thing. In Italy, when someone comes to eat, you don’t bother with preliminaries; you go straight to the table. When the doorman rang to let me know that Claiborne was coming up, I turned on the heat under the saucepan of water in which I was to cook the pasta and put the cooked veal rolls back in the pan to reheat them. When Claiborne came in, however, he said he wanted to interview me before we sat down to eat, so I rushed back to the kitchen to turn all the burners off. When the interview was over, I turned on the heat under all the pans again, and I brought the artichokes to the table. We had just started on the artichokes when the doorman rang to say that there was a photographer from the Times downstairs. Claiborne had him come up, saying that if I didn’t mind, he would take some photographs before we continued with the meal. Back into the kitchen I went to turn off all the fires, convinced that the veal was going to be leather-hard by the time I finished warming it up again. Miraculously, every dish was very good, and Craig, who in the years to follow would become a close friend, was enchanted. On the following Thursday, Craig’s story covered the better part of a page. He printed my telephone number, and my cooking classes sprang to life again. It was October 15, 1970. I have never since then had to be concerned about how to occupy my time.

Marcella and Victor shuttled between Italy and New York with their young son, Giuliano, and they always spoke Italian at home. Consequently, when Giuliano was enrolled in the third grade at a New York school, language was one problem he faced. Lunch proved to be an even bigger hurdle, because the other children ridiculed the food he brought from home. Marcella substituted innocuous sandwiches for homemade tortelloni with ricotta and parsley or cannellini- bean soups, but realized that she, too, faced the same cultural chasms.

I had a call one morning from a woman at Giuliano’s school who said she was organizing an event for parents and children. “There is going to be a buffet,” she said, “and I was hoping that you could contribute a dish.”

“Certainly,” I said.

“Could you bring some Swedish meatballs?”

“Oh, I don’t know what they are.”

“Can you make a tuna casserole?”

“I am afraid not.”

“How about a chicken casserole?”

“I don’t even know what you mean by ‘casserole.’”

“Well, all right,” she said, sounding somewhat cross. “Can you contribute a dozen bottles of Coke?”

“Certainly.”

“Can you bring them next Thursday evening?”

“I’ll have to send them with someone, because on Thursday evening I have a cooking class.”

“Of course, I understand. I hope you are making progress.”

In the spring of 1973, Marcella’s first cookbook, The Classic Italian Cook Book, was published to enthusiastic reviews, and demonstrations on television weren’t far behind. Newfound acquaintances such as James Beard, restaurateurs Tom Margittai and Paul Kovi, and actor Danny Kaye became friends for life.

Like others who have been nurtured by the settled life of a small town, I have never felt a strong urge to expand my habitat. I am not a self-promoter, but New York is a bellows that can fan great flames from small sparks. In the year that my cookbook was published, I was invited to dinners and parties, and in a few months, I had met nearly everyone in, or at the margins of, the city’s food world. I immediately felt strong empathy for and from James Beard. I was startled at first by the open-air shower that he had in the back of his house on West Twelfth Street, but I soon understood that it wasn’t crude exhibitionism; it was a manifestation of his natural candor, of his aversion to cover-ups. I was amazed by what he knew and remembered. He was my living encyclopedia: Whenever I had a question, he had the answer. He had a sonorous voice that he used as a foil for the mischief in his eyes. His laugh was magnificent, rising from deep within his capacious belly. An example of it still rings in my memory’s ears. Sometime after we had become friends, we were both giving cooking classes in Italy—Jim at the Gritti Palace, in Venice, and I at my school in Bologna. He phoned me there to ask a question about an ingredient.

“Marcella!” said the booming voice. “I came across a recipe in an Italian magazine I would like to use. It’s for shrimp with a beautiful pink sauce, and it sounds delicious, but it’s driving me nuts.”

“What’s the problem?”

“There is a mysterious ingredient in it that has to be essential to the pink sauce because nothing else in the list has that color. I have looked it up everywhere, but there is no description of it in any of the sources. I hope you can help me out.”

“I hope so, too. What is it?”

“Rubra.”

“Oh, sure, Jim, it’s ketchup.”

“Ketchup?”

“That’s right. It is the best-known Italian brand of ketchup.”

Ho, ho, ho, the big laugh came rolling over the phone line, over and over, such a happy laugh, as though he had just heard the funniest joke in the world.

Tom Margittai and Paul Kovi, both Hungarians and both executives at Restaurant Associates, became the new operators of the Four Seasons and the Forum of the Twelve Caesars restaurants when their company divested itself of those two properties. Paul was very old-world, wearing well-tailored three-piece suits, the vest crossed by a gold watch chain and resting on a prosperous paunch. He spoke English with a suave accent and had an air of great connoisseurship. When he found out that I came from Cesenatico, he said, “I know it well. When I was young I played on a professional Italian soccer team, and we trained near there.” He was the only person I had met in New York who had been in my hometown. Tom was jet-settish, fashionable, and briskly entrepreneurial. Both became generous friends.

Tom offered to give my cookbook a boost by hosting a fortnight at the Forum of the Twelve Caesars restaurant based on my recipes. For $25, one could have an antipasto, a first course, a second course, sal-ad, and dessert. Three Italian wines were included. The event was to run from November 11 through November 23, but it was so successful that they held it over until December 7.

I was there every evening to talk to guests. One evening Tom told me to expect Danny Kaye, who was coming with his daughter, Dena. Danny left me no opportunity to talk to anyone else that evening. I learned that cooking was one of his great loves. He had others, of course, including piloting airplanes and dabbling in a variety of medical subjects, but he was obviously an extremely well-informed and deeply committed cook.

I discovered too that, aside from Italian cooking, we had another culinary passion in common: Chinese food. Danny described the special Chinese kitchen he had built in his Beverly Hills house. He had gas burners with several concentric rings able to reach such high temperatures that, to make getting close to them tolerable, he had had to install a steel trough in front of the stove with a stream of ice water circulating through it. “Do you know how the Chinese make chicken lollipops?” he asked me. “Come into the kitchen and I’ll show you.”

If you are Danny Kaye, you can walk into a restaurant’s busy kitchen unannounced and ask someone to give you a chicken thigh and a knife. He loosened the skin at the knob end of the bone, scraped the flesh upward to leave the bone clean, and turned the skin inside out over the thick part of the drumstick. “There! You now have a chicken lollipop ready for frying. Let me know if you come to California,” Danny said, “I’ll make you a Chinese dinner.”