The balloon was not supposed to fly over the dunes. It was supposed to rise with the sun, drift over the pale green savanna and the bone-dry bed of the Tsauchab River, and ease to the edge of the red Dune Sea in southern Namibia, the centerpiece of what’s known as the Oldest Desert in the World. The undulating sand mountains around Sossusvlei—at sunrise, they’re colored the vermilion of a dragon on a Japanese kimono—are the arresting face of one of the most barren, most peaceful, and least-known countries in southern Africa, one that’s nevertheless becoming the next frontier of luxury travel.

I had arisen long before dawn at nearby Little Kulala, one of three upscale camps run by Wilderness Safaris, a conservation collective begun two decades ago to promote ecotourism across southern Africa. Little Kulala, situated on a private reserve, has 11 thatched villas—complete with air-conditioning, plunge pools, and open-air mattresses for stargazing—decorated in muted grays and beiges that are more Calvin Klein than Ernest Hemingway.

The lodge is adjacent to Namib-Naukluft National Park, which hugs the Atlantic coast. The park, the largest in Africa, is almost twice the size of Massachusetts. But it’s not the only mega-desert in Namibia; the Kalahari runs along the country’s eastern border, abutting Botswana. In effect, Namibia (the name means “vast open space” in the language of the Nama people) has a desert to the east, a desert to the west, and very little in between. Although it’s twice the size of California, it has a population about the same as that of Houston—just 2 million people concentrated in the north, where rain is more plentiful. On a U.N. list of population densities, Namibia ranks 225 out of 230, barely ahead of Mongolia. Neighboring Angola, by contrast, has 5 times as many people per square mile; South Africa, 15 times; and Rwanda, 137 times.

For all practical purposes, Namibia is empty.

The main reason for this vacuum is the harshness of the terrain. When the European powers were eagerly divvying up Africa in the 19th century, even they were put off by the rugged conditions. Beginning in 1884, the Germans did eventually annex the territory as South-West Africa, but South Africa, a British ally, took it over during World War I. South Africa eventually lost the territory as the result of an uprising led by the Marxist South-West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), formed in 1960. Namibia became independent in 1990.

Still, the new country has few resources. (It reminds me of that old joke about Moses wandering 40 years in the desert before picking the one place, Israel, that had no oil. Moses would have loved Namibia.) Half the inhabitants depend on agriculture, mostly subsistence farming, for their livelihood. There are some minerals, but the uranium and diamond mines have been well picked over. Even the mackerel and hake fisheries, once the backbone of the economy, have suffered from overfishing, currency fluctuations, and rising fuel costs. Flying north one day above the Skeleton Coast, a fearsome stretch of the Atlantic where countless ships have run aground in the wind and fog, I asked the pilot of our four-seat Cessna about all the vessels anchored in the harbor. I had heard that ships had been prospecting for new diamond supplies offshore.

“They are fishing boats from Spain and Lebanon,” he said.

“And what are they fishing for?”

“Sardines.”

Ah. Profitable, perhaps, but hardly a growth industry. Namibia is depleted.

But therein lies its allure. Most first-time tourists to sub-Saharan Africa come for the game. They stay in one of the pricey hideaways that have proliferated in Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Botswana, and they go on game drives at dawn and dusk to spot the vaunted “big five”—lion, leopard, elephant, Cape buffalo, and rhino—and enjoy luxurious beds, spa treatments, and a bottle of French Bordeaux with their Cuban cigars. While these dream getaways provide a fantasy introduction to Africa, they are, well, passive. What sets Namibian travel apart—and what makes the country an ideal destination for a second trip to the continent—is that it is active. Game is not the focus of a trip here; the enormous sweep of countryside is. And in most places you can get out of your Land Rover and walk right into it.

The best place to do that is Sossusvlei, where the dunes, which form a natural corridor along the riverbed, summon the adventurer to climb them and experience, firsthand, the strange ecology of living sand. Like many things in Namibia, the sand on these dunes comes from someplace else. The red-tinted grains—which, depending on the time of day, change in color from apricot to sweet potato to cardinal—come from the eroded sediments in the Orange River (which forms the border with South Africa), flow northward from the cold South Atlantic in the Benguela Current, then gust eastward onto the Dune Sea. The farther inland the dunes are, the redder they become, because the freshly blown grains mix with older sand, in which the high iron content has had more time to oxidize.

Climbing in the dunes (some of them 1,000 feet high), as visitors can do at famed Dune 45 or the gigantic Big Mama and Big Daddy, you realize that they aren’t static but constantly shifting. Much of each dune is held in place by vegetation and inner moisture. But the tops move like slithering snakes, as year-round winds blow sand onto the slip face and send it avalanching down the leeward side. The peaks can migrate as much as 25 feet in a year. Put footprints along one face while climbing up, and by the time you climb down an hour later, they will be gone. In Sossusvlei, the dunes are alive.

Water is the other great mystery of Namibia. Terrain is classified as arid if it gets no more than 100 to 200 millimeters of rain a year. The Namib Desert gets less than 50 millimeters of rain annually, making it extreme even in the realm of desert climes. So everything has to adapt. Springbok survive by eating plants that store water in their leaves. Elephants, which survive on less food and saltier water and have smaller bodies, longer legs, and larger feet than elephants elsewhere in Africa, break their tusks digging up roots and bulbs. A local beetle, the tok-tokkie, rests on the west side of the dunes in the morning with its head facing downward. Droplets of fog condense on its back, then drip down its head and into its open mouth.

“If you came here during the summer,” advised my guide, Angula, “you’d never come back. It’s so hot—sometimes a hundred and twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit—and so windy, I would have to carry you and beg you to put clothes on.”

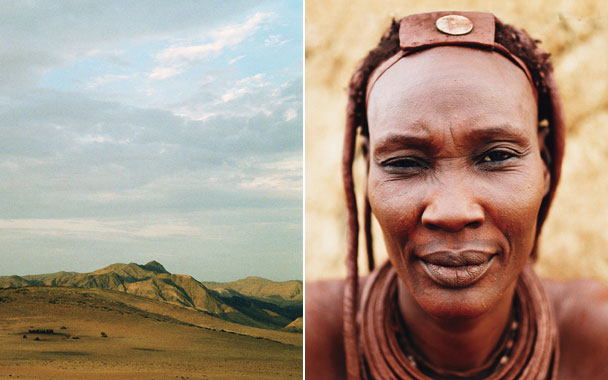

It’s not just the desert that’s forbidding here. Up north, where the Kunene River divides the mountains of northern Namibia from the even taller peaks of southern Angola, the landscape reminds me of Asian scroll paintings, with looming mountains on one side, rolling dunes on the other, and, way at the bottom, a winding river lined with a tiny ribbon of green. Studying this kind of art in Japan years ago, I learned one secret. The special something that holds the scene together is the human element—the bridge, the lantern, the artist contemplating nature. In this case, the human element is a collection of thatched cabins, built on stilts and huddled beneath a thicket of ana trees. This is Serra Cafema, the five-star tree house at the end of the world.

There’s little to do at Serra Cafema other than experience the inhospitable yet breathtaking terrain. Over several days, I slid down the banks of dunes on a four-wheel quad bike, hiked along mountain crests, and visited a nearby village. The Himba, one of the smallest of the dozen or so tribes that inhabit Namibia, are pastoral and build their dung huts in a circle around a livestock corral in order to protect their animals from hyenas and other predators. Women cover their bodies with a terra-cotta-colored mixture of red ocher and goat fat that moisturizes and protects their skin, which they wash as seldom as once a year.

Any hopes I had that I might enjoy a float down the river were quickly quashed by the presence of a gargantuan crocodile right outside my hut. Crocs are a deadly reality along the Kunene: One of the village women had been nicknamed Crocodile after being attacked while washing clothes; and a camp employee had lost her four-year-old daughter, who was seized by a crocodile while fetching water.

The stock-in-trade of the African luxury safari lodge seems to be this tension between living close to the wild and enjoying otherwise unattainable sumptuousness. Serra Cafema uses generators to run electricity and pump water to its showers and has a small pool where guests can swim without fear. Nearly all the food that arrives in a seemingly endless procession of meals—breakfast, morning tea, lunch, afternoon tea, sunset cocktails, dinner—is flown in. Local beef and oryx (a large antelope also called gemsbok) are accompanied by heavy, German-style sauces and sides, followed by bread pudding.

I asked the Namibian chef what he would cook if his president were to arrive for a visit. “Oryx fillet,” he said, “with a wine sauce. Like all game, oryx is leaner than beef. Plus, it’s on our coat of arms.”

On my last stop in the country, Etosha National Park, oryx were plentiful, along with many of the big five. In two days of game drives, we saw an extraordinary array of animals, including elephant, white rhino, eland, giraffe, the yellow-billed hornbill—a.k.a. the flying banana (Zazu in The Lion King)—the rare Hartmann’s mountain zebra, and 20 lions. One reason for the abundance: The rainy season had been an unusually generous one, and many animals, understanding that this meant their young had a better chance of survival, responded by mating more than once in the same year. We had stumbled into a rainy baby boom.

Our guide, Sunday, explained why the heavily built oryx—with zebralike stripes on its head, white legs, and long black horns—is the symbol of Namibia. First, he said, it can survive in the desert. Like the camel, the oryx can raise and lower its blood temperature to cool down its brain and can go for long periods without water. Second, because it is very brave. “Even humans have been killed by oryx.” And third: “Because it is very beautiful.”

Beautiful, brave, able to thrive in the desert. A perfect symbol of the country.

Namibia is extreme.

Which was exactly what I was thinking that morning on the balloon ride. As we lifted off at sunrise and climbed into the air above Sossusvlei, I was struck by the variations in starkness below—the impoverished riverbed, the endless vista of dunes on one side, the craggy mountains on the other.

But even though the balloon was supposed to stay over the riverbed and not venture above the dunes, a sudden gust sent us off course. Our pilot, Willem, attempted to steer us back, but we lost altitude rapidly and headed toward the crest of one of the dunes. “Hold onto the edge of the basket,” Willem instructed. “Bend your knees. If we tip over, try to fall backward.”

For a second, it seemed as though we were going to crash. The basket brushed the top of the dune, with its tufts of grass the color of sea oats. I held my breath.

Then, suddenly, we slid past the summit and back into the air. There was total silence. We were safe. And looking down at the landscape, I no longer saw the parched ground or the deadness. I noticed the liveliness of the grass. I noticed the acacia trees lining the banks of what will become a torrent of water during the next rainy season. I noticed the ostriches sprinting on the open plain. Underneath this bleakness lie hidden lines of life. Here, the invisible is animate.

“There is nothing in Namibia,” said Willem, after he had landed the balloon neatly on the back of a truck, sliced open a bottle of Champagne with a machete, and served a four-course breakfast, complete with fresh apricots, muesli, home-baked croissants, and zebra jerky. “No minerals. No business. This is a tourist destination, full stop. And I love it. As far as your eye can see, this is my playground.”

This is the gift of Namibia. Being in such an extreme environment forces you to look beyond the aridity to the meridians of moisture hidden underground. You cannot merely receive this place, you must pursue it. Namibia may be empty, but being here makes you feel undeniably full.