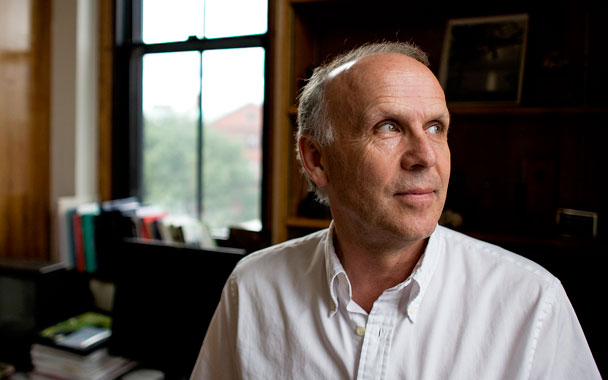

In his new book, Catching Fire, Richard Wrangham, Ruth Moore Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University, makes the case that cooking was the definitive evolutionary step that made us humans what we are. Gourmet contributing editor Jocelyn Zuckerman spoke with Wrangham about surviving in the bush on a chimpanzee diet; the health claims of raw foodists; and whether cooking can be blamed for the universal subjugation of women.

Jocelyn Zuckerman: According to your “cooking hypothesis,” you believe that it was cooking food—more than eating meat, more than agriculture, more than the advent of tools—that made us who we are, correct?

Richard Wrangham: Yes. People get rather aerated when one says more than this, more than that, but I think that for many people, the point at which Homo erectus emerged—1.8, 1.9 million years ago—was the most dramatic moment in the course of human evolution. And I think that was caused by cooking. Our ancestors from two and a half million years ago had been eating meat, and there’s no question that meat was very important. Agriculture also had immense impact on the total population size and the size of our communities, but it didn’t seem to have the same sorts of changes in our physiology as cooking.

JZ: Can you talk about the nutritional benefits of cooked food?

RW: The two big benefits boil down to, first of all, that cooking increases the digestibility of the specific nutrients. For example, cooking increases the digestibility of starchy foods. If you eat raw starch, then much of it is resistant, which means that you’re not getting the full benefit from it. If you cook it then you get much more energy out of it. So the first big thing that cooking does, and it’s very predictable, is to increase the proportion of the nutrients, particularly starch, but also protein, that goes through your body and is actually digested, as opposed to being passed out unused.

The second thing is the body does a lot of work to digest food, and we know this, of course, because after a heavy meal you feel sleepy. If you do the research you can see that the blood carries oxygen to the tissues of our intestines and away from our peripheral muscles, so no wonder you feel sleepy and physically unenergetic—because your body is doing work to digest, and the amount of work is quite significant. It can be ten or twenty percent of the total caloric value of the meal. Cooking softens the food. It makes it easier for the body, therefore, to digest, just because it is softer and more easily accessed by liquids, more easily churned up by the muscles in the stomach and so on.

There are various experiments that I cite in the book that show this dramatically. [In] the one I love, you take the ordinary hard pellets that rats are given in the laboratory, and you change them simply by adding air—that turns them from something like a wheat grain to a puffed wheat. Then you feed two groups of rats either the hard one or the puffed one; you give them exactly the same number of calories; and you monitor their locomotion so that they spend the same amount of energy involved in locomotion. The ordinary theory would predict that they would gain weight at the same rate. But now when you think about the cost of digestion, you think, well, wait a minute, maybe the one eating the puffed pellet would do better, and indeed they do. They gain weight faster and they have 30 percent more body fat by the time they’re adolescents and early adults.

JZ: And there’s also all the time involved, right?

RW: Think about it: Plato said that intelligent animals are the ones that spend very little time eating. And it’s quite clear now from a number of time-and-motion studies that we spend less than an hour a day chewing our food, whereas if we were a great ape of the chimpanzee-gorilla type, which our ancestors were once, we would be spending something between five or six hours a day eating on average. That would completely change the nature of our lives, because in addition to just literally chewing, you’ve got to find the food. But once you cook, then the food is soft, you can chew it quickly; it radically changes how you spend your time. The irony is, if you look at hunters and gatherers, who are the great evolutionary model for us, women pretty much translate the time gained by cooking into preparing and cooking food. So they appear not to have gained very much. But the men have been freed. Because in all hunter-gatherer societies, just like in every society around the earth, except nowadays some families in modern industrial society, women cook for men.

JZ: That’s a particularly provocative part of the book—where you draw a straight line from the advent of cooking to the subjugation of women.

RW: Yes. I mean, a straight line is a dangerous thing to say, but we do see these very strong influences.

JZ: Why do you think people like Charles Darwin and Claude Lévi-Strauss paid so little attention to cooking?

RW: I think one of the [reasons] is that people found it difficult to think that something as cultural as cooking had really been incorporated into our biology. People always thought about biology as something that did not involve anything as complex as cooking. And there were just no hints, or people never followed up on any hints, that humans are biologically adapted to cooked food. We know that we can eat all sorts of foods raw. And probably people just assumed that humans were like other animals and could eat their food raw and survive on it. For me, it was following chimpanzees, and trying to eat all their food, and sometimes going without any human food all day: I saw that you couldn’t survive on it.

JZ: And it consisted of what, exactly? Berries and leaves?

RW: Something like two thirds of their diet, by the time spent eating, is fruits. But the fruits are not oranges and apples and kiwis and strawberries. They’re like crab apples or something. They’re very dry, and they taste, well, the kind way to put it is “strong,” but basically nasty. You can’t get many of them, and they don’t have anything like the amount of sugar that domesticated varieties do. We’re used to eating fruits that have been the result of several thousands of years of agricultural selection. And if you go out into the wild and start trying to fill your stomach with fruits from wild shrubs and wild trees, you’ll find it very difficult.

JZ: They tasted terrible and you were hungry all the time?

RW: Yes, absolutely. I wouldn’t have survived unless I came back every night and had delicious bowls of steaming pasta.

JZ: So you don’t give much credence to the health claims of present-day raw foodists?

RW: I give a lot of credence to some of the health claims of raw foodists. The fact that I don’t think raw diets are natural does not undermine their claims that they get various kinds of benefits. One benefit of course is [raw foodists] lose weight. Another benefit is that [the diet] reduces various kinds of allergies. I can well believe that some people are sensitive to some of the compounds produced by cooking. I don’t think everybody is.

JZ: Can you talk about how cooking influenced our socialization patterns?

RW: It’s very speculative, but it’s so striking that everybody feels delightfully comfortable around a fire, and once you have fires and meals around a fire, it draws people together in a way that, as somebody who watches chimpanzees, is strikingly different. In general, in animals, where you have individuals living in close proximity on a regular basis, they find ways of solving various social problems, and this can be built into their evolution. Humans as a species, compared to chimpanzees, our closest relatives, are extraordinarily tolerant. We can look into each other’s eyes and chat to each other. We don’t lose our tempers very easily with each other, compared to chimpanzees. This looks like a species that has been through selection for tolerance. We’re clearly just a very nice species in many ways, in terms of our social manners. And so it’s easy to imagine that this, to some extent, happened as a consequence of the importance of being able to gather around a fire and share meals without fighting over them.

JZ: So the chimps don’t tend to sit around in groups and hang out?

RW: They don’t. I mean, on one level you can just chart up the raw data on how often they lose their temper or have some kind of impulsive aggression and get into a fight. And it’s something like a hundred to a thousand times the frequency of humans. And then how do they feed? Well, you can get a whole party of chimps in a big tree feeding together, but they’re all feeding in their own individual little stations. And if there’s ever a monopolizable food source, a chunk of stuff that you can put in your arms and walk away with—like a big bunch of bananas—under those conditions, then fighting breaks out. And the fighting is very intense. I mean, they stamp on top of each other and bite each other and chase each other.

JZ: Males and females alike? Is everyone is in the mix?

RW: Everyone’s in it. The females tend to be very nervous, but if a female is so hungry and drawn to the food, then she’ll reach a hand in or try to get a piece, and she can get beaten up, just like the others. But it’s mostly males beating on males. And these are tremendous fracas. There’s an enormous contrast to what happens when a man brings an antelope into the camp of a hunter-gatherer group, or a woman comes back and unfolds an animal cloak and reveals all her food. And again, if someone’s cooking their food, a nice big meal, and some strangers come into camp, they do not follow the chimp style, rushing and attacking.

JZ: And the woman’s part in that contract is that she makes the food?

RW: Yes. It’s kind of a primitive protection racket. The woman is protected from having her food taken. And in exchange she cooks for a man, the husband, and then he provides the conduit into the social group, who will protect her if a bachelor comes along and tries to take her food. One of the things that continues to fascinate me is the difference in the status between bachelors and married men.

JZ: You talk about that in the book, and about how, in some societies, a bachelor’s first wife could easily be a post-menopausal woman.

RW: The society I quoted in the book is the Tiwi, of northern Australia. And the thing about them is that they are polygamous, so one man can have up to 20 wives. And so the bachelors find it very difficult to get wives at all. In every society, bachelors are very keen to get a wife, but there, the ones that are most often available are when a man dies and leaves widows. And so 80 percent of them are older than [the bachelors] and many of them are post-menopausal.

I think what that is revealing is the essential nature of marriage in hunter-gatherer societies. Which is, what a man really needs is a woman who can give him the status of being an elder. Because once he’s married to a woman who is going to cook for him every night, then it does two great things for him. One is that it enables him to go off during the day and do things that men are culturally supposed to do—all the manly things of hunting and going off to war and so on, and still being able to count on a meal when he comes back. And the other thing is it enables him to be a host.

JZ: So does that translate to modern western society? Would you say that when it comes to finding a wife it may be, even subconsciously, more about cooking than about sex?

RW: Well, clearly our society has really emphasized the importance of sex. Yet I think there are fascinating explorations to be made in this area. Of course everything is complicated by the availability of fast food and restaurants, not to mention just packaged food, which is very easy to cook. So I’m uncertain as to how deep this goes in modern society. But I would think there are some really interesting questions to be asked about, as the consequences of the easy availability of food, has this really contributed to the breakdown in the marriage system? And this sort of shift towards what is viewed as important in terms of sex, and whether we’re forgetting about these critical household domestication issues.

JZ: Has this cooking idea infused all your research now, or are you moving on to something different?

RW: Well, for 22 years now, I’ve been studying this community of chimpanzees in western Uganda. I’m following the soap opera of their lives and looking at all sorts of aspects to do with their social relationships. So I’ll continue to do that. But I’m just so totally intrigued by this whole cooking area. I’m sure one of the things that came out in the book is my repeated astonishment at finding out how little has been explored around the significance of cooking. So it’s going to be very hard for me not to continue playing with it.◊