A fishery-management approach called “catch shares” might be the key to stopping rampant overexploitation of marine resources, according to reports delivered this week at the Seafood Summit in San Diego.

In theory, the concept behind catch shares (which are also discussed in a recent opinion piece in The New York Times) is simple. First, figure out how many fish can be sustainably caught; then allocate them equitably to those who want to catch them.

Each fisherman is guaranteed a share, not only for the current season but also for the future. Like property, that share can be sold, leased, bought, or traded. Fishermen get what amounts to an ownership interest in the future of the fish stocks.

Compare this to the traditional approach, where limits are set and then it’s every fisherman for himself in a race to get as many fish as he can, as quickly as he can, any way he can—a marine version of the old land rush. Or, as Kate Bonzon of the Environmental Defense Fund put it, an adult equivalent of a children’s piñata party. The goodies spill out and everyone dives in—because if little Johnny doesn’t grab a candy bar, then little Judy will.

Bonzon said that catch shares were currently used in 30 countries. Comparisons of fisheries before and after the program was put in place show dramatic turnarounds. Before, catch limits were exceeded 65 percent of the time; after, there was no overfishing. By-catch (unwanted species that are caught and dumped back into the ocean, usually dead) fell by 40 percent. Safety of crews more than doubled. What’s more, revenues that were falling by 10 percent a year increased by 70 percent.

Wes Erikson, a British Columbia fisherman, gave a graphic description of what happened when that province’s halibut fishery switched over to catch shares in the mid-1990s. In 1990, more than 400 vessels caught that year’s limit in a hectic period of six 24-hour days. Fishermen died because they went out despite poor weather. Boats swamped when they became overloaded with fish. And those fish were of poor quality because boats stayed out as long as they could, and once they returned to port with their none-too-fresh catch, the entire year’s supply of halibut had to be frozen and warehoused. “It made us look bad, and we were bad,” said Erikson.

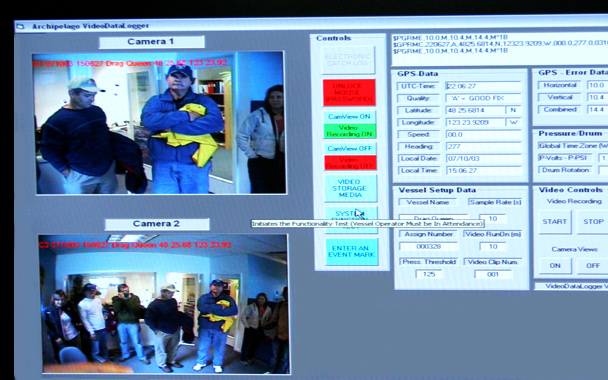

As is typical, the B.C. fishermen resisted catch shares until it became evident that their choice was either getting with the catch-share program, or leaving their boats at the docks because there would be no fish to catch, period. Today, cut-throat competition is a thing of the past. The catch is carefully recorded and monitored. Each boat has video cameras that photograph every creature that comes aboard. Bad fishermen (“the bandits and pirates,” said Erikson) who couldn’t or wouldn’t abide by the new policies sold their quota to those who did. Now, the fishermen catch their shares gradually over the course of the year. Top-quality halibut are landed daily. And the once-dying B.C. halibut fishery is about to receive certification as completely sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council.

Erikson even has enough time to indulge in another of his passions. He opened a sushi restaurant. Nothing gives him more pleasure than serving fish he has caught himself.