Enough already with the weather! It is oppressively unstable, every day, every night. This is a land where children freeze to death walking five blocks home from school in a blizzard. This is a land where homesteaders fed up with the endless rattle, dust, dry heat, and scorching-hot winds of August walk out to the barn and hang themselves for the relief. This is a land where a farmer goes to bed with fantasies of 180-bushel-an-acre corn, then listens to the wind and hail all night long shred his dream. This is a land of high anxiety. Citizens of the more benign farm environments to the east don’t understand the drama of weather on the northern Plains, the terror of knowing that you can work hard from sunup to sunset and still have no control over Mother Nature.

On July 31, hurricane-force winds, monitored at more than 100 miles per hour, roared through the Christenson brothers farm in Brown County, South Dakota. How does a top-heavy corn stalk in the middle of pollination survive 100 mile-an-hour winds? Wind breaks—thousands of trees planted over decades by Rollin Christenson and his sons to provide shade and wildlife habitat—hold the soil and snow, filter the rain, and for one night in August when the wind howls, keep fragile corn tassels from blowing to Kansas. “We lost some corn,” Scott Christenson told me philosophically. “But we figure we really needed the rain that came with the wind. So we’ve told ourselves that the rain offset the wind.”

Dale Hargens and his daughter, Andrea, spent a slow, bitter week harvesting the two wheatfields that were wiped out by hail two weeks ago. The insurance adjuster spent two days walking the fields with Hargens and calculated that the loss averaged close to 40 percent. Hargens is still betting on his soybeans and corn. He dreams of 200 bushels an acre of corn, a once-in-a-lifetime bonanza. That’s the kind of harvest an Iowa farmer would feel good about. Along the arid 100th meridian, it is almost unheard of. Still two months to go … lots can still go wrong.

There is, in this region, an even greater uncertainty than weather: the roller-coaster prices of the global commodity market. Iowa flooded in the early summer, and on June 16, corn spiked to $8 a bushel on the Chicago Board of Trade. By the middle of July, Iowa farmers had replanted and now expect a good crop. Corn dropped to $6.20 a bushel on July 31. Faced with expensive feed stocks, ethanol plants cut back production, and marginal plants planned shutdowns. Corn contracts dropped even further, to around $5.60 on July 31. That’s a 30 percent price fluctuation in less than two months.

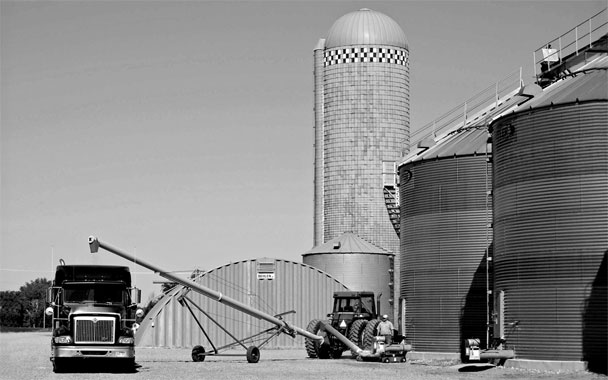

The strategy that farmers have embraced to fight the price roller coaster has transformed the aesthetic and cultural landscape of farm country. All across South Dakota, the red barn—an icon of family farming—is being replaced by the cold, gray steel of the grain bin, a symbol of industrial farming and the global commodity economy.

Grain bins lack the social intimacy of the old red barn. You don’t teach children how to milk a cow in a grain bin. You don’t store granddad’s old truck in a grain bin. Teenagers don’t make out in the hayloft of a grain bin. Nobody holds a harvest dance inside a grain bin. Charlie Johnson’s organic farm has a beautiful old red barn in the backyard. His wife wants to put on a new roof. But Johnson observes that it’s hard to justify the cost of something that won’t make a return. “The barn has aesthetic value,” he says, so he’s going to put the roof on. But he can think of other, better, ways to spend the time and money.

A 25,000-bushel grain bin can cost more than $60,000, and it exists for one purpose only: to give the farmer some small portion of control over the flow of his product into the market. Sometimes, it pays off handsomely. Last May, Johnson sold some of his ’07 organic corn for $10 a bushel. But prices can just as easily go south. Two years ago, corn sold for under $3 a bushel. Too many farmers have been caught in the bind of refusing to sell corn for $4, thinking it will go to $6, only to have it drop to $3. Jim Lutter thinks the storage movement has sidetracked farmers. “Why would anyone pass up the chance to sell $4 or $5 corn, thinking it will rise to $6? Just sell it. Take your profit and get ready for next year. If prices drop to under $3, you’re gonna want to sell it anyway. Who wants to be sitting on huge stockpiles of stored grain in a declining market?”

The Christenson brothers have gone in the other direction. Over the last decade, they have built storage bins able to hold 300,000 bushels. That’s an investment of nearly three quarters of a million dollars that gives them the ability to sell corn every month of the year. They are not alone. “The demand [for storage] is so great,” says Scott Christenson, “if we wanted to order a new bin for next year’s harvest, we’d have to order it today, and it still probably couldn’t get built in fourteen months.”