Tap picture to advance the slideshow.

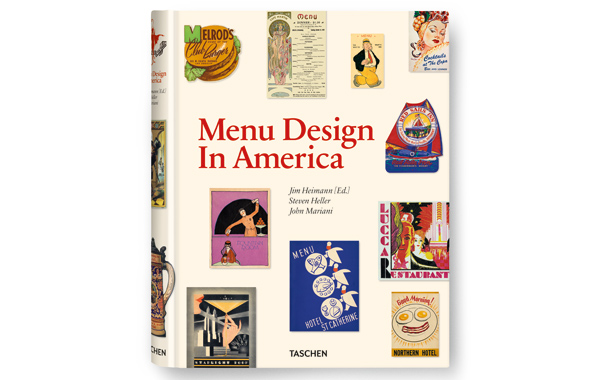

If Jim Heimann had lived in Renaissance Europe, he’d surely have had a private museum of curiosities, containing dodo eggs, unicorn skulls, and the like. Since he was born in mid-20th-century California instead, he has a museum-quality archive of curiosities of a different kind, relating to Americana of all sorts, including car culture and the history of design. Heimann’s collection includes printed materials, original photographs, artifacts, and, by no means least, some 5,000 menus, representing high-end restaurants, roadside stands, and everything in between. Heimann is a lecturer, pop anthropologist, designer, executive editor at Taschen America, and now editor of Menu Design in America: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design 1850–1985, a magnificent large-format, three-language, 400-page survey by Steven Heller and John Mariani of this surprisingly profound subject.

Standing in his labyrinthine Los Angeles archive, surrounded by boxes of meticulously catalogued menus, Heimann explains to me that the book’s final form took some time to determine. “Initially, we thought we might do menus of the world, but the American material was so rich, we knew we had to focus.” His own collection was always meant to play a central role, and it was supplemented by archival material from the Culinary Institute of America and the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University, among other institutions. “But it turns out there really aren’t that many collections," Heimann notes. "So we started looking for individual collectors, and then somebody said, Well, you know, the best menu collection in the world is right around the corner from you in L.A.”

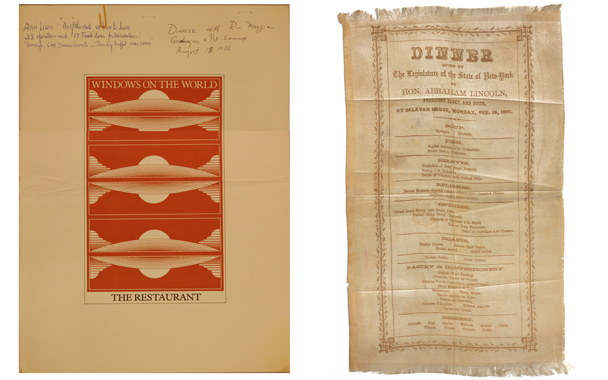

On making contact with this collector (who still wishes to remain anonymous), Heimann found him very welcoming and his holdings a revelation. “It trumped all the other collections,” says Heimann. “I handed him a wish list. There were key menus I was looking for, such as the Lindbergh dinners after his transatlantic flight. I knew there was a dinner in Paris, and I knew there must have been one in New York, and when we met this collector, he said, ‘Well, which one do you want?’ It turns out there were 40 of them. After Lindbergh came back from Europe, he barnstormed across the country and they had dinners in 40 different cities.” Three examples made it into Menu Design.

By necessity, Heimann acknowledges, “the book is in part ‘the best of,’ but I also wanted to tell a story. Once I saw the scope of what was available, I realized there’s clearly a tale here of American eating.” In fact, the book contains a double narrative, of the menus’ form and content—that is, the food they offered. Some readers will focus primarily on the beauty of the designs—the extraordinary convergences of color, illustration, and typeface. There’s the cover of a wine list from the Burlington Route railroad that I find just exquisite. Readers may also be amazed and amused by menus in the shape of pigs, crabs, bunches of bananas, or conga drums.

Other readers will prefer to regard the menus as social documents. One of the earliest in the book dates from 1861, documenting a dinner given by the New York State Legislature for President-elect Abraham Lincoln; terrapin soup and larded grouse were among the options. Toward the end of the book is a menu from Windows on the World, which crowned the North Tower of New York City’s World Trade Center before it was destroyed on September 11, 2001. Both artifacts are reminders that something as simple as a menu can have tremendous resonance.

“I started collecting menus as a kind of research tool for my earlier book California Crazy, about vernacular roadside architecture,” Heimann explains, “but because so many of them had incredible graphics, it became obsessive—especially [those from] the drive-ins. And then I wanted to know what Americans ate when they ate out. And did Americans eat out very often prior to the car and the 20th century? And the answer is that before then, most Americans didn’t go out at all. Most of the menus from the late 19th and early 20th centuries are from big banquets and formal occasions. Only people who had the means availed themselves of ‘dining out,’ and there was a social structure imposed on dining. Many early restaurants were strictly all-male establishments.”

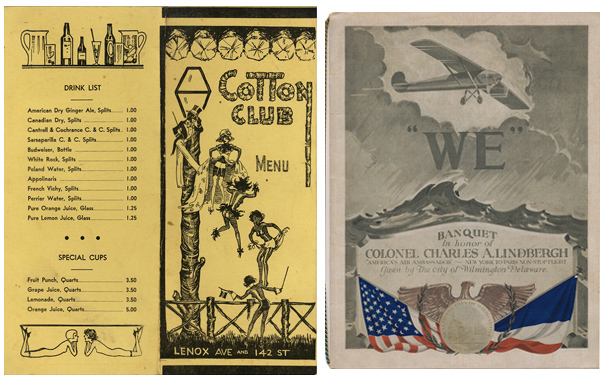

Naturally, the menus record changes in culinary tastes and fashions, the rise of fast food, infatuations with tiki and the smorgasbord, and famous and infamous names such as the Cotton Club, Delmonico’s, DiMaggio’s, and Trader Vic’s. Some things remain remarkably stable: Meat and potatoes, it seems, have always been with us. Some things change constantly; there is probably a Ph.D. thesis to be written about the rise and fall of America’s relationship with the frog’s leg. But the menus also record and reflect key chapters in American society: wars, Prohibition, notions of “healthy” eating, the space age, and especially patterns of immigration.

The book is full of surprises as well. Who knew that KFC once provided rather elegant printed menus? Who would have thought that in 1902 there was a Los Angeles restaurant named the Vegetarian that served gluten gruel, eggplant on toast, and “protose steak with jelly”?

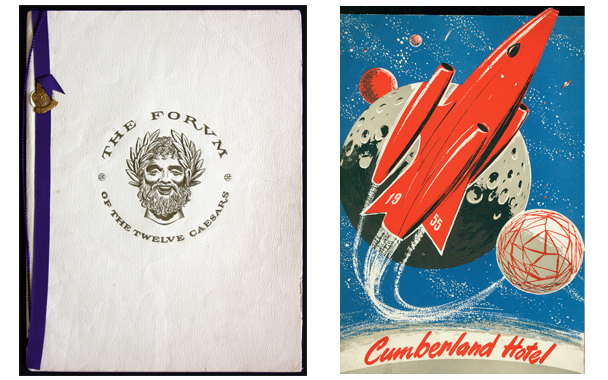

“If there was a golden age of menu design,” Heimann ventures, “I’d say it was the 1930s. There were wonderful things going on in the big cities, even though it’s the middle of the Depression. L.A. had all the Hollywood nightclubs, New York and Chicago had great restaurants, and most of the menus used fine illustration. And they had some wonderful regional ingredients available: L.A. menus featured bison and rattlesnake. When you get into the ’70s and ’80s, everything drops off. Illustration is replaced by photography; nobody wanted to spend so much money.”

One restaurant in the book makes me wish I had a time machine to take me back there: the Forum of the Twelve Caesars, located in New York City’s Rockefeller Center in the late 1950s and early ’60s. (It made a brief appearance on Mad Men, which got the menu design dead right.) According to Heimann, it was “a very distant predecessor of the ‘theme restaurant,’ but it wasn’t intended to be campy. They were really trying to re-create a sumptuous classical Roman banquet.” There you might have had Lucanian lamb sausage, sylvan venison, alpine snow hare, and “crepes of the mad Nero.” OK, maybe not all of that is strictly authentic, but it still sounds pretty good to me.

Heimann reckons he’s been a collector since the age of 2—he started with rocks—and he’s not about to stop now. His treasure trove grows daily, and he’s much less finicky about the menus he acquires than many of his counterparts. “There’s a collecting mentality that everything has to be mint,” Heimann observes, “but personally, I don’t really care, because it comes with the territory—you find menus with wine or marinara sauce on them. A lot of them were taken as souvenirs, so they have fold marks, because people stuffed them in their coats. That’s how I get all my contemporary menus. If I’m going with a female companion, I ask her to bring a big purse.”

Geoff Nicholson is a writer in Los Angeles. His books include the novel The Food Chain and the nonfiction Lost Art of Walking. Nicholson’s previous articles for Gourmet Live include “Drinking In Shirley Temple and Charlie Sheen” and “Funny Food.”