From a squeaky office chair in his Boulder, Colorado, bedroom, Mario Lurig looks into his Webcam, takes a short breath, and begins: “Hey Kickstarter, my name is Mario, and I want to tell you about chocolate dice.”

Over the next minute and a half, he walks a fine line between sales pitch and casual Skype chat. He talks directly to the camera about wanting to raise enough money ($950) to buy the materials necessary to mold and make edible versions of gaming dice—the 4-, 12-, and 16-sided types used in Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games currently enjoying a renaissance.

He put his pitch up on the Web site Kickstarter, a leader in the crowdfunding movement, in which artists, designers, musicians, filmmakers, entrepreneurs, and really anybody with a project and a plan can go public, seeking out enough money to turn their ideas into realities. Funds come from the general public, and in exchange for making contributions through Kickstarter, supporters are offered rewards that are meant to be commensurate with their donations; these can range from a postcard thanking them for their support, to a gift-boxed set of chocolate dice, to a tour of the Iberian Ham Trail (for committing $10,000 toward the construction of North Mountain Pastures’ charcuterie aging room).

Since its founding in 2009, more than a million people have contributed to Kickstarter campaigns. In 2011 alone, just over 27,000 projects drew a hefty $99,344,382 in pledges. Pledged money, though, is only collected if a project reaches a targeted funding level, meaning that if you back a project that only gets halfway to funding, no money is collected. Of those more than 27,000 projects, just under half met their funding goals, collecting something in the area of $84 million. This is where the proverbial wisdom of crowds comes into play: People tend to bet on winners.

The food category is a small but vibrant piece of the Kickstarter project mix; 241 food- and beverage-related projects brought in just over $2.8 million from 30,682 backers in 2011. The spread of funding requests reflects the general culinary zeitgeist—keyword searches turn up 118 beer projects, 80 tagged “vegan,” and 74 tagged “foodtruck.” And then, of course, there is the great common denominator, cupcakes, with 50 listings, including 8 vegan cupcake projects, 6 cupcake trucks, and 1 beer cupcake.

Food and drink projects, though, can be a tough sell; if you’re trying to get supporters for a book, film, or music idea, it’s easy to give potential patrons a sample of what you have to offer. Food, though, requires a greater leap of faith. There are no little tastes on the Internet, and as is often the case with new, small ventures, word of mouth is scarce. People who contribute are buying into not just the project but also the story behind it, and the process of bringing it to life. “Backers get to watch each chapter unfold and enjoy behind-the-scenes access to the process, which can foster really strong emotional connections to the project,” Kickstarter director of communications Justin Kazmark says. “For the creator, running a project is as much about engaging with that community of supporters as it is about finding funding.”

Fair or not, the creator’s ability to present the story of a project in a compelling way is one of the major factors that separate the successes from the duds. It seems that not everyone who goes to Kickstarter for funding understands that the medium demands—for better or worse—entrepreneurialism as entertainment. Mario Lurig, the chocolate dice maker, remembers one doomed aspirant who presented her plan to open a candy store to him for analysis. “It was a one-paragraph description—no video—and the rewards didn’t connect with anybody. There was no plan. It was simply, ‘I would like your money, because I want to have a candy store.’ It’s like me putting up a project, saying: ‘I’d like to be an astronaut. Who wants to pay for me to go to space camp?’”

At this point it is almost axiomatic that a compelling video is necessary for a project to be successful. For example, North Mountain Pastures gives a two-and-a-half-minute tour of their Pennsylvania farmstead with a sincere, understated voiceover, and violin backing that brings to mind a Ken Burns documentary. Homesweet Homegrown, in soliciting support for a canning and preserving cookbook, took an opposite approach, showcased in an 11-minute video of its gloriously sozzled authors putting up jars of tomato sauce; it’s loose and eccentric—like the great British TV chef Keith Floyd reimagined by the makers of Portlandia. And some, like the one for (organic, non-GMO, sustainably packaged) Quinn microwave popcorn, are so pitch-perfect that our current crop of presidential candidates would be thrilled to have their creators in their employ.

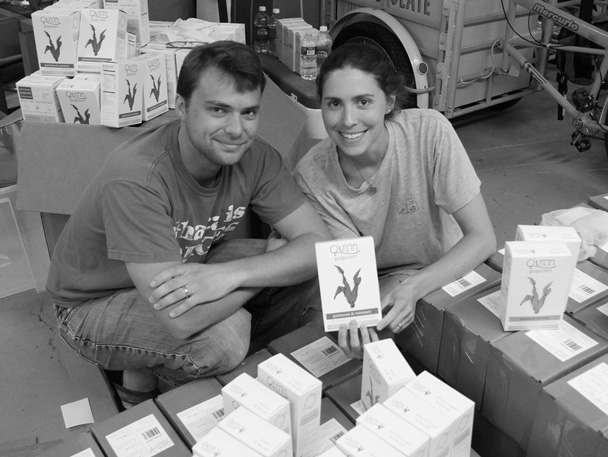

Before launching their Kickstarter campaign for Quinn Popcorn, founders Kristy and Coulter Lewis researched not just popcorn but Kickstarter itself. “We spent a little bit of time watching videos, and knew instantly what worked, and what didn’t,” says Kristy. “It’s really hard to sum up your brand in a sentence, so we took images of what we loved. We wanted to show that it’s not something that comes from a factory in China.” What the husband-and-wife team came up with was high-grade Americana: images of cornfields and pickup trucks, horses and friendly dogs, and their newborn son (the company’s namesake), all set to upbeat acoustic guitar music. As a piece of branding it was undeniably effective.

Liz Zapf was moved enough by the Lewises to contribute. “You got, from the beginning, that they really cared, and were excited about their idea and that they were kind of nervous about doing this,” she says. “You could see that they were doing it for the first time, and that it was a big punt.”

And for the Lewises, it was a big punt. After maxing out their credit cards and tapping friends and family for all they could, Kristy and Coulter still needed, at minimum, another $10,000 to bring their first batch of 6,000 two-bag boxes to market. Along with Zapf, 754 other people bought into Quinn Popcorn—more than 300 people contributed $35 for a box of each of three flavors: Parmesan & Rosemary, Lemon & Sea Salt, and Vermont Maple & Sea Salt.

In the case of Quinn, the transaction was pretty straightforward: The Lewises made a packaged- food product, and that was what supporters were getting for their contributions. Getting the product into the hands of consumers was the goal. The infusion of capital and word of mouth from the campaign were enough to attract the interest of vendors like Whole Foods and Dean & Deluca. The Lewises have already sold 75 percent of their second batch of 20,000 boxes, and are scrambling to get a third batch ready before the popcorn runs out.

Making and selling a packaged-food product is not the only way entrepreneurs use Kickstarter. Restaurants have also been turning to Kickstarter for seed money, though the amounts raised are almost never enough to be a restaurant’s sole source of funds.

In Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights neighborhood, two New York restaurant veterans (they both worked at the very popular City Bakery), Sara Dima and Ilene Rosen, used Kickstarter to find an additional $10,000 to offset the opening costs of their cafe, 606 R&D. Their pitch focused on one aspect of their incipient project, the acquisition of a Donut Robot Mark 1 machine, finding the lucrative intersection of two things Kickstarter patrons love: donuts and robots. A dollar contribution got you a donut on your first visit to the café, and $1,000 got you the privilege of creating a custom flavor and then spending a day manning the robot as it churned your namesake baby out.

Knowing that they had enough money to open their business with or without a Kickstarter-funded donut machine allowed Rosen to take a somewhat more bemused attitude toward the campaign. With a wry smile, she admitted to finding the process of making the video “dreadful,” but overall enjoyed the process of mounting a Kickstarter campaign: “It’s fun. It feels like online dating. With cash.” She adds, “Really, either it’ll be all good, or it’ll be all good plus 10 grand.”

The “all good” Rosen was talking about was the publicity that a well-constructed campaign can generate. 606 R&D had just been featured in the Huffington Post and in New York Magazine. Quinn Popcorn found its way to Daily Candy and The New York Times, and Mario Lurig’s chocolate dice went from Reddit chatter to Gawker’s gaming news and culture site, Kotaku. All managed to reach audiences outside of the existing Kickstarter universe, which in turn created more attention from Kickstarter itself—getting featured in one of Kickstarter’s “projects we love” emails can turbocharge the attention/money cycle. North Mountain Pastures, who had been bringing in pledges at a steady clip since their mid-January launch, saw more than $11,000 flood in over the three hours after the company was featured in a recent Kickstarter email. All good, indeed.

Eventually for Rosen and Dima, it was all good plus 10 grand. For Quinn popcorn, it was all good plus 27 grand. And for Mario Lurig, who hoped to get $950? All good plus 16 grand.

Matthew Kronsberg is a producer and writer living in Brooklyn, New York. He has covered a variety of topics for Gourmet Live, including cooking with marijuana.